Celestine

Celestine

Great wars of liberation are being fought all across North Africa and the Middle East. Lesser wars of liberation are being fought in France, too. Here in the fifth arrondissement of Paris, we battled the forces of French bureaucracy to liberate our household goods from Le Havre customs.

We valued most of the fifty boxes at $50 each. Many contained books, writing supplies and journals. Many contained art. How do you assign such things a dollar amount? Customs was suspicious. ALL were the same value? Were we smuggling precious objects to sell in France, without declaring them, so we didn’t have to pay taxes? Or forbidden items?

The struggle to release our stuff took forty e-mails, twenty phone calls, 300 euros and three weeks, but we triumphed.

One week ago, the boxes were delivered to our door. The man who drove the truck three hours from Le Havre carried some of the boxes down to our cave[1], most of the boxes to our apartment, and with the help of a Romanian worker named Christian, he carried my maternal grandmother’s heavy wooden trunk up five flights of stairs, since it wouldn’t fit in the ascenseur.[2]

The truck driver, a shy, florid man in his 50s, who looked as if his favorite pastime was eating, seemed ready to pass out as he entered our living room. Christian, younger and fit, was smiling, unfazed.

The driver accepted a glass of water, but would not take a tip.

Christian stayed all afternoon, helping us slice open boxes with sculptures and paintings inside. He broke down the cardboard boxes for recycling, while we greeted beloved works of art as if they were old friends who’d made a long journey across the country by covered wagon, then a voyage by slow ship across the Atlantic, only to be held unlawfully in jail for nearly a month.

Are objects alive? Of course. How else to explain the numinous quality, the spell cast on us, by the things we unpacked?

These things spoke to us! They told us stories. Sometimes one would break into song.

Time or space won’t allow me to tell you every single story we heard in the several days of unpacking, but here are a dozen:

1) The trunk. The big, round-backed, dark brown wooden trunk belonged to my Norwegian-American maternal grandmother, Esther Moe Heimark. Esther was a poet and playwright who also bought antiques, which she sold in the small Minnesota town where she lived with my grandfather, Julius, and their three children. This trunk is the perfect size to contain the following:

i) My grandfather’s accounts of his parents crossing the United States by covered wagon, farm life in Minnesota, and leaving the farm to become a doctor.

ii) Copies of my uncle Jack’s Heimark family history, with photos.

iii) Genealogical books about my Kitchell family ancestors, Puritans who fled religious persecution in Kent and Surrey, England, and arrived in Guilford, Connecticut in 1639.

iv) My own oral history interviews with my parents, transcribed and bound as a gift to my family. How strange and heart-breaking to read it and hear how lucid my father was, just a year or so before his dementia began.

2) A bentwood chair, also of dark wood, from my grandmother Kitchell’s apartment in the Sequoias assisted living apartments in San Francisco, where I and my cousins Kit, Mark, Liza and Hank visited her often in the two years before she died. She was always warm and nonjudgmental towards my then-boyfriend, Gary, a wild and wooly bohemian painter. An American blueblood herself, I never saw one instance of snobbery from her.

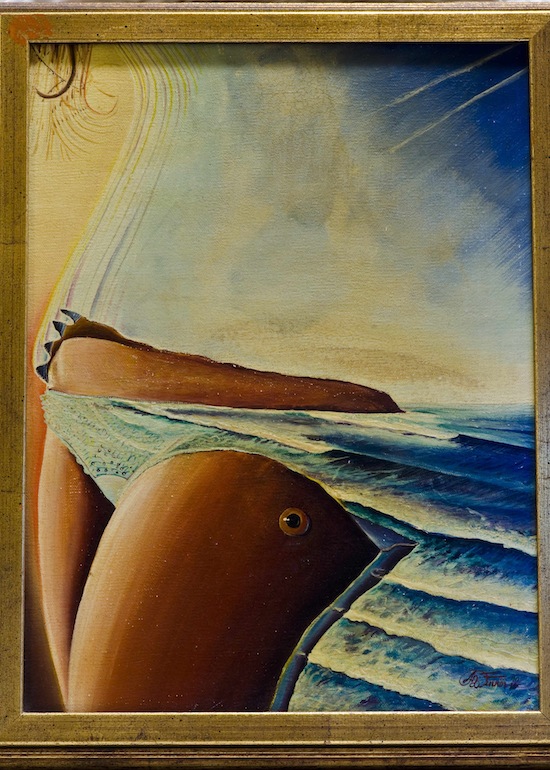

3) Dana Point, a painting that Gary painted, shortly after we left the schooner, The Flying Cloud. We had lived on it for two years, renovating it to go around the world. The painting has three levels: landscape, woman’s body and bird. It is surreal, like the work of Salvador Dali.

4) Celestine, a papier mâché bear and two tree branches that my sculptor sister, Jane, made to honor our father. I first saw it in her art studio in Boulder, and bought it half a year before her nearly sold-out art show at my brother, Jon's, and his wife, Leatrice’s, art gallery in Phoenix, Arizona. Celestine stands in the non-working fireplace of our living room, leaning forward eagerly, just as my father did in life.

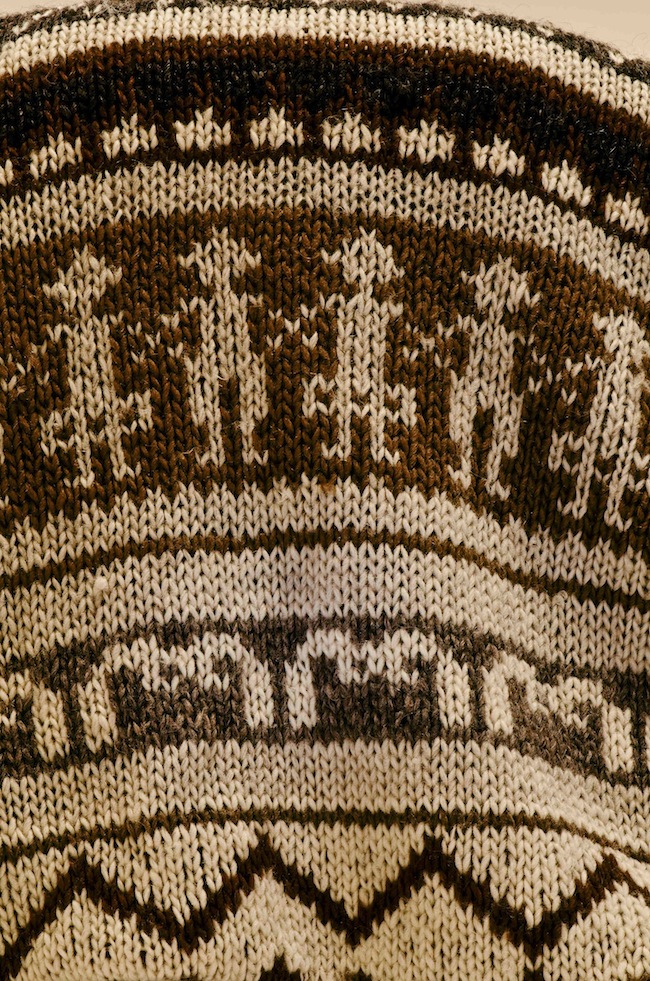

5) The soft wool blanket with bears and men and women holding hands that my mother knitted and gave to me. I told her I repaired a couple of holes Marley had made in it while kneading me as I read in bed.

“Oh, that was the worst thing I ever knitted,” my mother said.

“But it’s beautiful!” I said.

“I mean, it was the most difficult of anything I ever made.”

6) A painting by Kathleen Morris, Shrine for Couple #3, from my Santa Fe years when I earned a living as a traveling art dealer, which brought me to Los Angeles. I stayed in a suite at the Chateau Marmont in the late ‘80s, a very good time for selling art. I began to find the excitement of the city more appealing than living in the country in Santa Fe, and moved to Los Angeles in 1990. And there I met Richard.

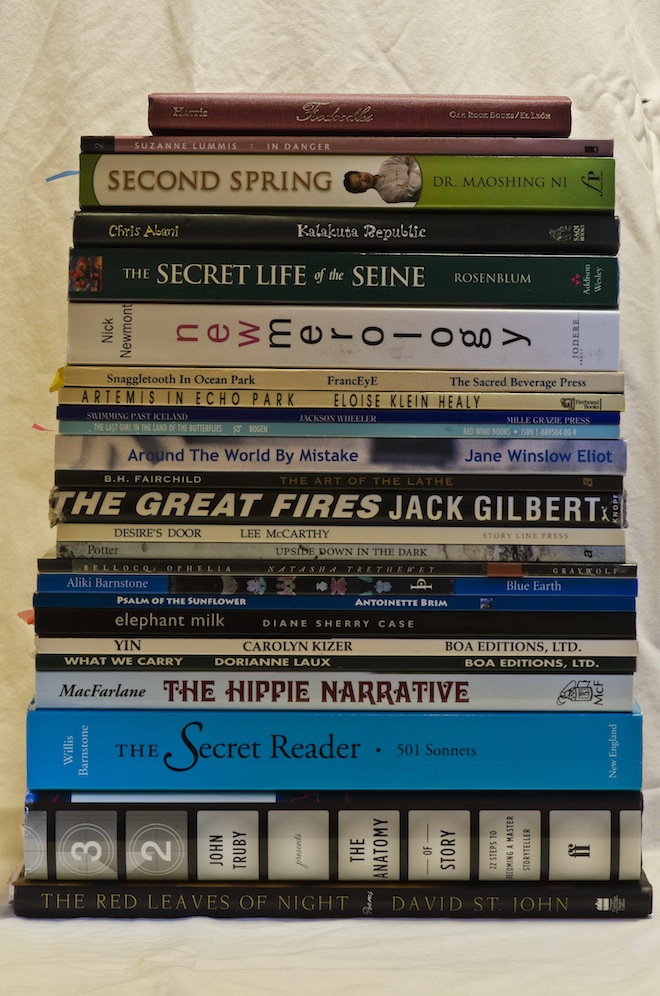

7) Books by friends. Richard and I met at a 1994 poetry reading at a bookstore, Midnight Special. Later, with three friends, we started a poetry reading series at the Rose Café. It lasted three years, and exposed us to all the rich work of the poets of Los Angeles, and later, from other parts of the country and beyond.

8) The photo of Carolyn Kizer reading her poems at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books. She was the first person to read at our series at the Rose Café, and became my poetry mentor and friend. Later, we bought the Paris apartment she and her architect husband, John Woodbridge, owned.

9) Prayers to the Muse, the cross that my sister, Jane, made for me when I received my M.F.A. in creative writing at Antioch University, Los Angeles. It is made of red leather book end papers and dry wall mud. Antioch gave me more friends than any other experience I’ve had in my life. Six of them joined me weekly for a fiction reading and editing circle at our house in Playa del Rey for years, which continues now with us Skyping between Los Angeles and Paris.

10) Charlie the marble. I opened a well-wrapped package and out tumbled Charlie. Charlie, a photographer, was married to my great friend, Polly, with whom I lived in two communes in Berkeley in the late ‘60s. Richard and I loved visiting Polly and Charlie in their warm, art-filled Berkeley home over the years. Charlie died several years ago after a liver transplant. A glass artist whose work Charlie photographed took his ashes and made 300 glass marbles out of them as gifts for his friends. Richard and I each have one, which we keep on our desks and play with. Richard wrote a sonnet to him. We talk to Charlie. He’s so pleased that Polly’s painting and sculpture are being shown in various galleries, well reviewed and selling well.

11) My sister, Jane, made a modern Kachina, The Minotaur, for Richard. He is a Taurus. It captures his Bull spirit, and now raises its arms in the goddess salute of ancient Crete in the nonworking fireplace in his office. (We were married in Crete, since our personal myth originates there.) The heavy stone at the base made it very difficult to ship to Paris. But we found an art packer, Jorgen, at Box Brothers in Santa Monica, who devised an ingenious way to keep the stone from breaking away from the papier mâché figure, and this totem figure arrived intact.

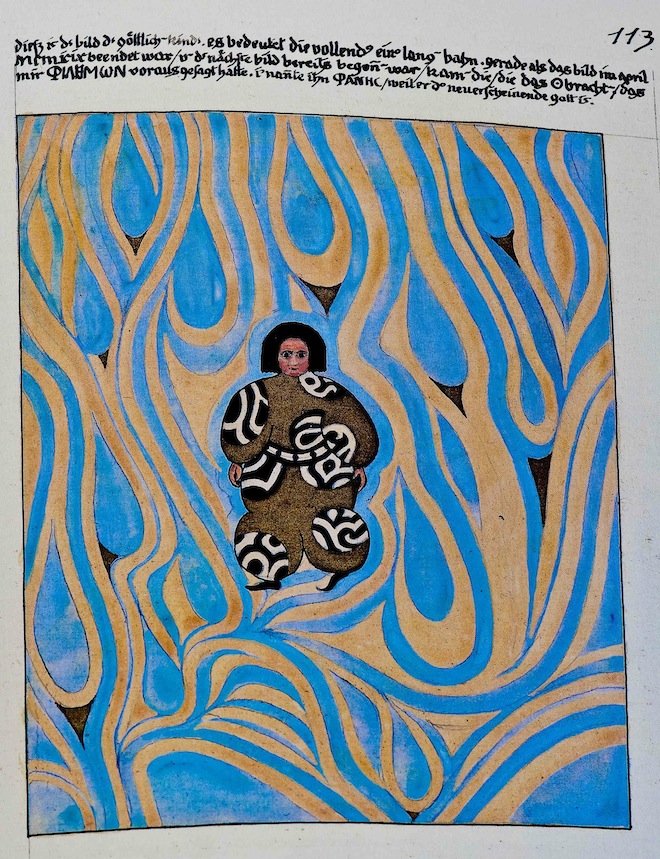

Page 113, The Red Book

Page 113, The Red Book

12) C. G. Jung’s The Red Book. Richard and I saw a show at the Armand Hammer Museum in Los Angeles of this magical book of mandalas that the great psychiatrist, C. G. Jung created as a vehicle for his own healing. This may be a universal method of healing; drawing a daily mandala was my way of healing, too. For my birthday last year, three of my siblings, Jon, Ann and Suki, gave me a book certificate. I bought this book with it. It is so numinous that I can’t read it yet. But at the right time, I will.

[1] Storage units in the cellar of the building for each apartment owner. The caves are ancient, eerie and cold. You can imagine Edgar Allen Poe setting one of his stories here.

[2] Elevator.