At Paris security check-in: a stack of trays, a line of travelers waiting for space on the conveyor belt. Someone has left his bag in the tray on top of the column. Several men stand behind the stack, nonchalantly chatting, blocking other travelers in front of them from getting trays.

“Whose bag is this?” I ask.

The man lifts it (insolently), as I pick up a tray, plops it back in before I can take a second one.

The Australian woman between the man and me says, “Travel has gotten unbearable.”

“Hasn’t it though.”

One of my bags is held up. Whoops, I forgot to throw away my dangerous weapon, that bottle of water. The security agent asks if I’d like to drink it. Such an unexpected courtesy in today’s travel. Yes! Apologize and thank her.

In seats past security, Richard and I lace up our shoes. The Australian woman is nearby with a girl who looks like her daughter.

I go up to her. “I just want to say I think the whole world is divided between people like you who are awake, and people like that narcissistic egotist who put his bag on top of the stack of trays.”

“Wasn’t he terrible?” she says. “He shoved in line between me and my daughter.”

“Just charming.”

“Thank you for saying this to me.”

Richard and I find seats in the gate area with two and a half hours to wait for our plane. To the right, several young men on high stools play video games. The varieties of mindless escape are everywhere and multiplying.

In a café area to the left, a man and woman in their late 40s, she with lips so swollen she looks like a blowfish, hair pulled back tight and blonde on her skull.

R.: “Do you think she’s had plastic surgery?”

K: “Ha ha, more like plastic savagery.”

The boys get up from their seats. A camera case remains on one stool. Richard grabs it, chases the departing young men.

“No,” says one. “It was there when we sat down.”

Richard opens it. There’s a memory card inside, no identification. “I’ll look at it when we get home to see if there are pictures that would identify the owner. What a lousy end to a Paris vacation, losing your photographs.” He goes to find a bathroom.

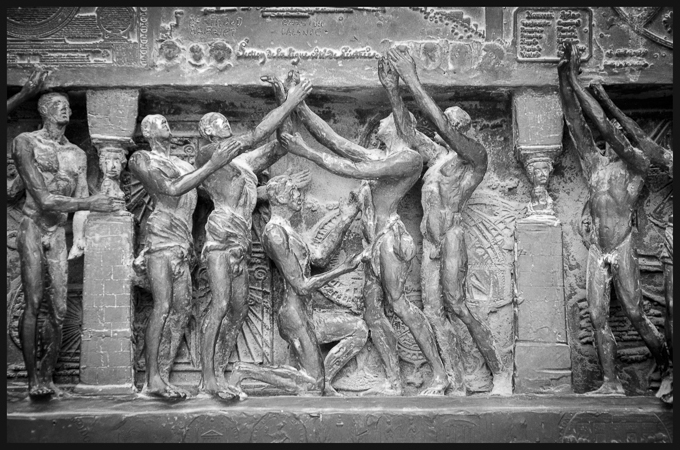

I open a paperback Richard found at a Left Bank bouquiniste, Joseph Campbell’s Myths to Live By. He quotes from R.D. Laing’s The Politics of Experience, about the briefly schizophrenic/shamanic experience of Jesse Watkins, a British wartime naval officer, now a sculptor:

“The voyager, as he tells, had a “particularly acute feeling” that the world he now was experiencing was established on three planes, with himself in the middle sphere, a plane of higher realizations above, and a sort of waiting-room plane beneath. … According to Jesse Watkins, most of us are on the lowest level, waiting (en attendant Godot, one might say), as in a general waiting room; not yet in the middle room of struggle and quest at which he himself had arrived. He had feelings of invisible gods above, about, and all around, who were in charge, and running things; and in the highest place, the highest job, was the highest god of all.

“Those all around him in the madhouse were on their ways—awakening—to assume in their own time that top position, and the one now up there was God. God was a madman. He was the one that was bearing it all: 'this enormous load,' as Watkins phrased it, 'of having to be aware and governing and running things.' 'The journey is there and every single one of us' he reported, 'has got to go through it, and you can’t dodge it, and the purpose of everything and the whole of existence is to equip you to take another step, and another step, and another step, and so on….'"

With ten minutes to boarding, I go to the restroom, get in line. A tall drag-queenish woman with long black hair butts in front of me, J’étais ici. She and a smaller blond woman in glittery tops and glittery purses with chunky chains, shout Arabic at each other in guttural voices.

Onto the plane. Richard has paid for seats at the wing exit so that we have extra leg room. His clammy hands signal his nervousness before flying.

An announcement: there will be a delay due to mechanical problems, which they hope to be able to fix. Terrific, just what Richard needs, proof that he has good cause to worry.

We talk. I read Myths to Live By.

“Astonishment! There is no “other” shore. There is no separating stream; no ferryboat, no ferryman; no Buddhism, no Buddha. The former, unilluminated notion that between bondage and freedom, life in sorrow and the rapture of Nirvana, a distinction is to be recognized and a voyage undertaken from one to the other, was illusory, mistaken. This world that you and I are here experiencing in pain through time, on the plane of consciousness of the ji hokkai, is, on the plane of consciousness of ri hokkai, nirvanic bliss; and all that is required is that we should alter the focus of our seeing and experiencing.

“But is that not exactly what the Buddha taught and promised, some twenty-five centuries ago? Extinguish egoism, with its desires and fears, and Nirvana is immediately ours! We are already there, if we but knew. This whole broad earth is the ferryboat, already floating at dock in infinite space; and everybody is on it, just as he is, already at home. That is the fact that may suddenly hit one, as “sudden illumination.”

45 minutes later we lift off. We pass over an extraordinary range of mountain peaks, high, jagged, capped with snow.

What are they? I want to know the names of these peaks and islands farther on. I listen carefully to the steward's announcements over the loud speaker. He sounds like Peter Sellers playing a role in which he’s messing around with the passengers by speaking French that’s too rapid and muffled to hear, English that’s even worse, with an atrocious accent added to the mix. I glance over at a Frenchman to our left. He shrugs, hands up.

I’ll ask a flight attendant. I take the flight magazine’s map of Europe to the back of the plane, ask the attendant in French if he would mind marking our path on the map. He’ll ask the pilot, he says.

“Do you know which island we just passed over?”

“Grow a sea.”

“Could you please repeat that?”

“Grow a sea.”

“What is the word in English?”

“I’m not sure. Grow AH sea?”

Back in my seat, I turn the word over in my mind. Surely I know this island. I’ve traveled this part of Europe and the Mediterranean before. Sudden illumination—Croatia! Maybe it’s the island of Zlarin, from which Richard’s paternal ancestors came, six generations ago.

The flight of three and a half hours seems swift. Just before we disembark, the flight attendant brings me the map, with an arrow passing from Paris south to the Adriatic Sea between Italy and Croatia, and down to Crete.

Everyone cheers as we land. The majority of passengers seem amazed that we made it.

At Nikos Kazantzakis Airport in Iraklion, we wait at Carousel Three for our bags. Mine arrives at last. Richard’s doesn’t.

We file a claim at the Transavia Airlines office. The agent, a dark-haired woman in her 30s, seems entirely relaxed. Much too relaxed, as if this happens all the time. Or is this just the Cretan manner, I remember now, no tension, no worry?

Our taxi driver finds us, shows us the sign with Richard’s name. His name is Constantine, he’d waited an hour outside, was worried.

“Does this happen often?” I ask the agent.

“Once in a while,” she says, as if, yes, bags do wander off to Switzerland or Sweden or right into someone’s home in Iraklion.

“Is there much theft of bags here?” She doesn’t seem to understand.

“Is it likely we’ll get the bag back?”

“Oh yes, probably by tomorrow night. We’ll send it to your hotel.”

Constantine has bottles of water waiting in his shiny black Mercedes taxi. He drives fast and expertly along the coast from Iraklion to the Mirabello Hotel. I ask him if he grew up on Crete. Yes, he did, in Aghios Nikolaos.

“And do you like living there?”

“Yes. But the Germans ruined our economy. The Euro austerity is hurting everyone.”

Richard asks him if we might stop at a market before arriving at the hotel. It is late, past 9:30.

Constantine calls the market, asks them to stay open for us, and they do. (Now here is one advantage of living in a small town.) The market is open all along its front, packed with racks of T-shirts, boogie boards, sunglasses, tanning lotions, and directly across from the hotel. This shocking hotel—how greatly it has changed since our honeymoon and marriage here in 1997!

A smiling golden-skinned Cretan woman greets us shyly at the entrance to the market.

Another older woman, radiant, benevolent, welcomes us from behind the cash register.

We find oranges, bananas, plums, Greek yogurt, walnuts, almonds, rosemary and olive leaf crackers, and six-packs of our two kinds of water, bubbly and plain. Pay and get into the cab with our bags to drive across the street.

The Mirabello Hotel, an earthy, funky, intimate place to stay right on the Cretan Sea. We’d stayed in a bungalow here to rest after a five-week honeymoon all over Europe. We’d had the vision here of how to shape our marriage vows right before the celebration with family and friends at Elounda Beach.

Only now! Now it is a mega-hotel, glossy, glassy, mammoth and utterly changed. In the lobby, deafening drums, the blasting sounds of disco. Huge sweep of marble counters, bare hard floor. The hotel clerk, a grim but efficient young Russian woman. We sign in and are immediately charged for ten days upfront.

We’re taken to the “village” across the street. The stone paths and planting remind us of Enchantment in Arizona; the white-washed bungalows, of Mykonos. The room opens onto a private patio and the sea, a net of jewels spread out in the town across the bay.

Richard has told them we’d been married here, were returning to renew our vows. On the table is an array of fruit—watermelon! pineapple!—and a bottle of champagne on ice. Rose petals are strewn across the pale blue coverlet. Rose petals float in the bathtub and across the counter and sink. Ah, this blissful world!