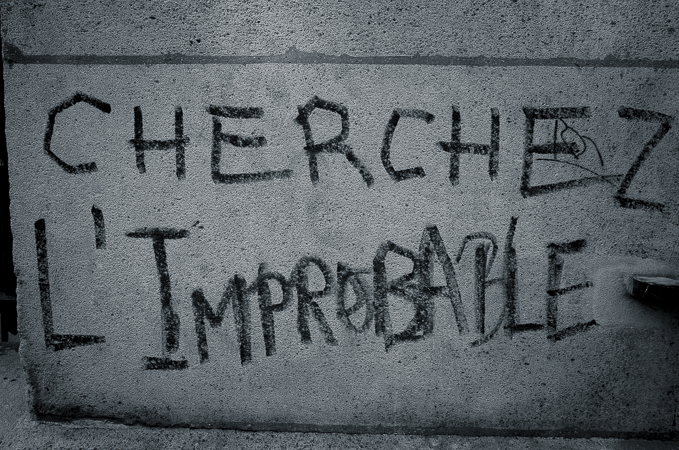

Street art © 2015 by E.L.K.

Street art © 2015 by E.L.K.

I was walking past the little café on rue des Écoles where all the kids stand in a clump smoking. I like to hold my breath as I pass them, so as not to inhale the smoke. It’s just one drug among many, I thought, but it’s probably my least favorite.

Richard tells me they’re starting to show a gangrenous foot here in France on cigarette packs; the images are much more vivid than on American cigarette packs, but then a larger percentage of French people smoke. It hasn’t become unfashionable here yet.

Approaching my café I saw one of my favorite waitresses off to the side, smoking furtively. She ducked her head as I came near. I could see by her body language that she was ashamed of smoking. I stopped and we talked. I asked her her birthday. In August, she said. I predict that by your next birthday, you’ll quit. I’d like to, she said, but first I need to have less stress in my life.

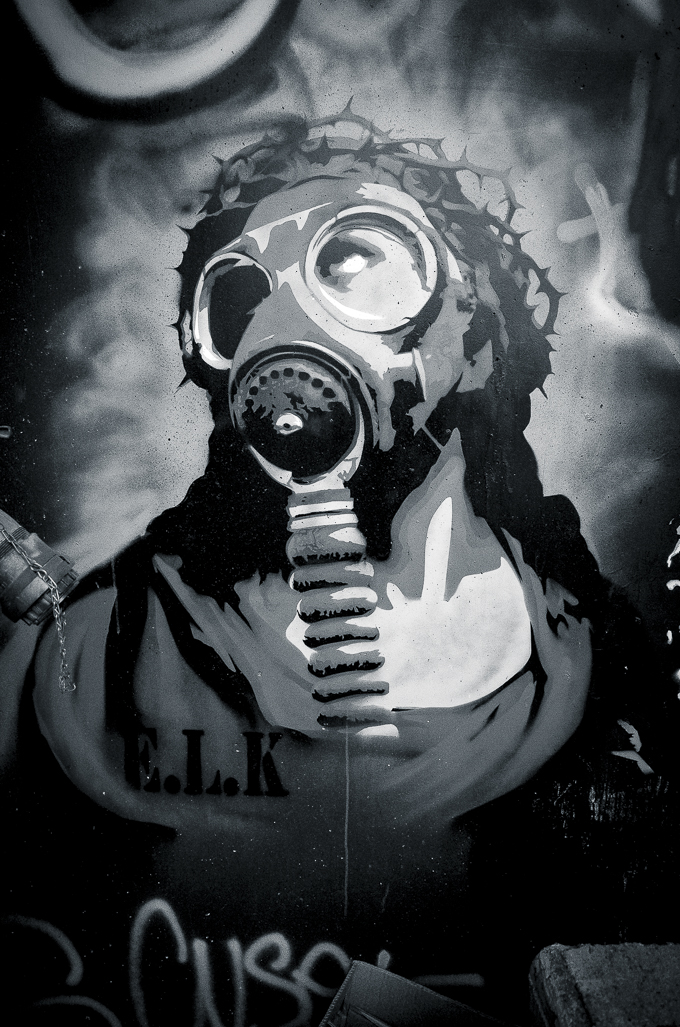

Street art © 2015 by PopEye

Street art © 2015 by PopEye

I told her the story of how I quit. I picked a date, which happened to be Valentine’s Day. I thought about it for a month ahead. Fourteen days in advance I smoked my usual fourteen ciggies. The next day thirteen. And so on, until the last day, on which I awoke, took a puff, put out the cigarette, put it in a baggie once it had cooled, lit it up later, took a toke, put it out, until at the end of the day, I got into bed and lit up the little snippet I had left. I took a deeeeeeep breath, and the ember fell on the dusky rose duvet and burned a nice big hole in it. I looked down and said, That’s it. Never again.

For the next two weeks I exercised like a lunatic, hung out in the sauna and Jacuzzi, and two weeks later the urge was completely gone.

Acupuncture is also good! she said.

It probably is, I agreed.

After my usual salmon and veggies, I opened my computer and chomped through a short story that I’d taken to a workshop the week before. I’d tried an experiment, making a draft of the story with everyone’s comments included in bold, with initials indicating who had made the comment. It served as a meditation on other perspectives. In rereading this draft, I could then make decisions: good suggestion, irrelevant suggestion, and skip over the spots where I wasn’t sure. Certain typos were no-brainers. Some of the suggestions involved adding to the story. As I made a decision about each comment, I eliminated it. Except one: someone in the workshop suggested changing a central metaphor in the story, because it was too familiar to her. But it wasn’t familiar to me. It seemed intrinsic to the nature of the character. I mused on this, and couldn’t decide.

At that point, this same waitress came up to me shyly, and asked in French (we only spoke in French), if it wasn’t indiscreet, could she ask me a question? Of course, I said. What do you do? I’m a writer, I said. What are you writing? A short story, I said. But I wasn’t sure if the word in French should be conte or nouvelle.

Nouvelle, she said. A conte is more like a fairy story.

Or The Thousand and One Nights? I said.

Yes, or Le Magicien Dose, she said.

I couldn’t quite translate that: Dose?

She said it again, and I laughed, The Wizard of Oz? D'Oz!

Yes, she said.

Street art © 2015 by Fred le Chevalier

Street art © 2015 by Fred le Chevalier

That’s magic, I said. I was just writing about the Wizard of Oz; it's a central metaphor in my story.

She smiled and scurried off to wait on another table.

So that was the metaphor that I was weighing whether to keep. Why did she mention this book, of all books? It was a sign to keep the story as I’d originally written it.

Hours later, I told her this.

Yes, she said, everything in the world is magic. Only some of us are open to it, and some are not. Some are closed and fearful.

We had each given the other an answer to a question neither of us had voiced aloud. But I’d heard her desire to stop smoking. She’d heard my question about my story. The nature of the world is magic, sympathetic magic.