At last! After a week crowded with workmen in the apartment, Giovanni painting, Marcus re-plumbing the shower, Richard’s first week of French lessons at l’Alliance Francaise, and the rush to meet our journal deadlines, tonight we have a date. Going to the Sufi dancing and dinner last week was so pleasurable that we decided to make it a once-a-week ritual.

Marcus will be here at noon to finish up the shower in Richard’s office. It should only take a couple of hours. But where is he?

I make a late lunch, omelette with onion, tomato, zucchini and mushrooms, with steamed broccoli and spinach on the side, and raisin toast, olive oil and almond butter. Just as I finish cooking, at 1:45 Marcus arrives, almost two hours late. He has brought his brother, Christian, who helped us the week before to unpack our boxes.

I want Christian to have a copy of our journal, The Numinosity of Things, since he is mentioned in it, so I print it out. The printer runs out of ink. It’s new, an unfamiliar Canon, and I don’t yet know how to put the ink in. Richard is out.

Just before Marcus and Christian finish their work, Richard returns. He replaces the ink in the printer, and I try again. It prints out half the pages and stops. Marcus and Christian wait, but we cannot figure out what’s holding up the pages, and we don’t want to hold them up.

Richard studies his French homework. I answer e-mail. Then we’re free to saunter over to the Jardin des Plantes[1]. Every once in a while, we crave the company of animals, lots of them, and there’s no place in Paris with a more wonderful assortment from around the world.

It’s so warm outside, 75 Fahrenheit and humid, I don’t even need a cardigan.

“Spring is really here,” I say.

Richard knows a short cut, past La Baleine Café, into the Jardin des Plantes.

And then we see—the combination of its being a weekend day and the first really warm day of spring has brought out half of Paris.

We pass the wallabies and stop.

“Look! They’re hopping around with babies in their pouches.”

“It IS spring,” says Richard.

At the entrance to the zoo, there is a line of at least 100 people.

We glance at each other. “Too crowded.”

“Let’s go to the Natural History Museum.”

But there, too, the line is too long. We meander into the gardens. There is the first display I’ve seen this spring of a uniquely French way of planting flowers, long beds of taller, bright flowers, in this case, pink and purple tulips in one; yellow, orange and white poppies in the other; alternating with long beds of lower flowers, small and white. The French pay attention to beauty, and this is truly beautiful. Couples lean down to get close to the tulips and look them in the eyes. Men and women take close-ups of the blooms. Richard joins them.

At the end of the long beds are flowering cerisiers[2], and a large tree with dark pink blossoms. Pelouse interdite[3] say the signs, but no one pays attention. Children laugh and run on the grass. Tourists and natives walk up close to the trees to look and to take photos. One cerisier is so thick with white blossoms that dozens and dozens of bees dally inside its branches.

We meander down rue Mouffetard. Let’s go check out a new restaurant a Parisian friend recommended, Dans les Landes, I suggest. We turn around and walk in the opposite direction down rue Monge. We pass Violette’s flower shop, and there she is, looking like a red-haired Colette, out in front, talking to friends.

At the restaurant, we find seats outside. The waitress asks us what we’d like to drink; we ask for the menu.

“Oh we don’t serve food,” she says. “Not till 7 p.m.”

It’s 5:00. Thierry, an excellent furniture maker and antique seller who sold us an armoire last week, highly recommended this place, but it won’t work for our date tonight. We cross over to rue Mouffetard.

Here’s a health food store that might have the vitamins that we’ve run out of. A trim French woman helps us find the best prices for each thing we’re looking for. We usually speak French with the French, but sometimes, when it involves looking for things like turmeric or 5-HTP or Ester-C, we revert to our native tongue. Better to be sure of getting what you want than to practice French for five more minutes.

A man wearing black leather and shades, a solemn caricature of an American film hoodlum, waits to speak to this woman. He begins speaking English, and we hear that he’s mocking us, as if we’re the kind of Americans who never bother to learn the language. I’m surprised. It’s not like a French man to be this openly mocking. Grouchy maybe, but not this style of rude jeering.

After the woman has finished helping this man, we have one more question, whether there’s a better buy of Ester-C capsules than the one we chose.

“Oui,” she says, and zips over to another shelf.

“He was mocking us, wasn’t he,” I say.

She nods. “He’s Belgian,” she says, as if that explains everything.

The man passes us on his way to the cash register.

“Blagueur. Moqueur[4],” I say.

He doesn’t respond.

At Delmas, where we usually have the best galettes in town, we sit in a corner. It’s early and there is only one other table of six young Italians near the door. We don’t need to look at the menu. We wait.

And wait.

And wait. No waiter appears. Finally a group of four men, dressed like Mafioso, come from another part of the restaurant and sit down to eat. One seems to be the owner or manager.

We tell him we’ve been waiting 15 minutes. He turns to go look for a waiter, but we say, “That’s all right. We’ve waited long enough.”

Everywhere we go today there seem to be obstacles. This is beginning to intrigue me. Some Saturnian spirit of obstruction seems determined to block us at every turn.

So let’s go to Picard Surgelés. This is a store that we passed often when we first started coming to Paris. It’s one of those words that is misleading for English speakers. Like traiteur, which sounds like traitor, but means “catering,” surgelés sounds medical. We’ve cleared that up, and heard from numerous French people and Americans how exceptionally tasty and high quality the French version of frozen food is.

The store is simply rows of freezer bins, well marked: soups, pastas, fish dishes, desserts, as antiseptic as a hospital. (You probably could perform surgery here). We stock up on pastas and soups, and leave.

Walking down rue Lacépède, Richard accidentally bangs my heel with the bag of frozen food. It feels like the back of my foot has been scraped off.

“You have no spatial sense,” I say. “I’m walking behind you now.”

(We are well-matched, we agree, he without a sense of space, I without a sense of time.)

He says he’s sorry, but it sounds perfunctory to me, a “man apology,” which by female standards, sounds like no apology at all. I’m in pain!

I, wanting a sense of empathy from him, ask for same. A small matter of tone, which women recognize instantly; men, not so much.

He gives a positively grudging apology. Now it sounds like self-defense, as if caring he’d hurt me was the last thing on his mind.

Being a woman, I point this out.

He begins to sing, "I'm Sorry," an old Brenda Lee hit.

It sounds like mocking to me. I say so. “Just say it like you mean it,” I ask.

He, being a man, explodes.

I shrink from his yelling in the street in horror. Sacré Bleu! Quelle horreur! In my family of origin you don’t shout in the street. You don’t shout, period.

Without a thought, without making a decision, my feet lead me straight across the street, as far as possible away from him. The date, it seems, is over.

But I want a date. Hmmm, who can I go out on a date with? Someone who is good company, someone who won’t yell at me. I know—me! What would she and I like to do tonight? Dinner? Or a movie? Well, why not both?

I meander down rue Monge to rue Lagrange, and Blvd. St. Germain, then right on Blvd. St. Michel until I come to Place St. Michel. There are French break dancers performing on the sidewalk in front of the fountain where Saint Michel vanquishes the dragon. I wish I could vanquish my own dragon, this passionately allergic reaction I have to what I perceive as callousness.

To me it seems so easy: you hurt someone; you didn’t mean to; but at least you can communicate to the other that you’re sorry. Nothing is more instantly soothing. And for me, nothing is more galling than when that generosity isn’t given.

I check the theaters along Blvd. St. Michel and Blvd. St. Germain. I’ve seen “Les Yeux de Sa Mère.” The others are lightweight French concoctions and heavily violent American killer-thrillers and action flicks. I muse on the question, “Do violent films inspire violence?” Of course they do. Wherever callousness is acted out or depicted, it increases the acceptance of unkindness, lack of empathy, cruelty.

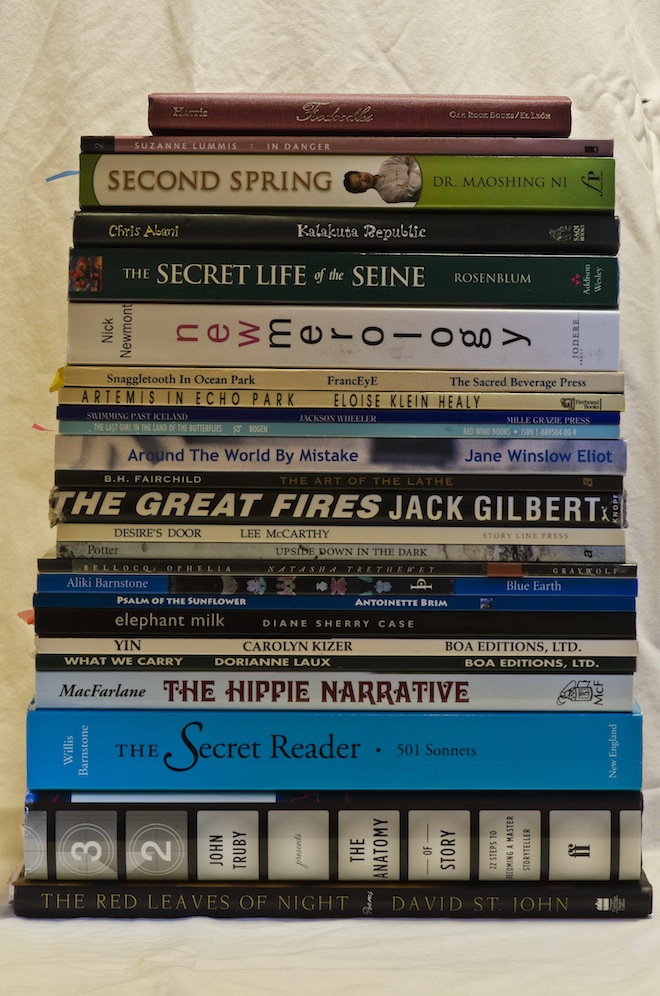

I keep walking. Maybe that theater on rue Serpente will be showing a good film. Yes, they are, but neither starts for an hour. Do I want to see a Spanish film about a photographer who sees the picture of a woman who died before her marriage and who then falls in love with her image (yawn), or The Fighter? I’ve heard raves about the latter, so even though it won’t give me my daily French lesson, that’s my choice.

I walk around the rue St. André des Arts area, looking at menus. Nothing appeals. Back on Blvd. St. Michel, and there is a Boulangerie Paul.

I order a tourte chevre courgettes[5] at the counter. The Asian proprietor heats it up. I take it to a table outside. The tourte is half cold. I don't want to take it back to be re-heated, or I might miss the movie. It's one of those days.

Five minutes later, the proprietor is outside, shooing away a group of three women who are seated, eating. He noisily stacks the chairs while people are finishing their meals. This is so un-French I’m shocked. I know of no other country where it is a national right to sit in a café, having ordered only a café crème, and read, write and converse for hours without being pressured to leave. He hurries a young African-American woman away from finishing her sandwich. I’d spoken with her at the counter and learned that she was from New Orleans, and yes, the town is healing but it still has a long way to go.

I gobble down my tourte and leave.

At the theater I buy a Perrier.

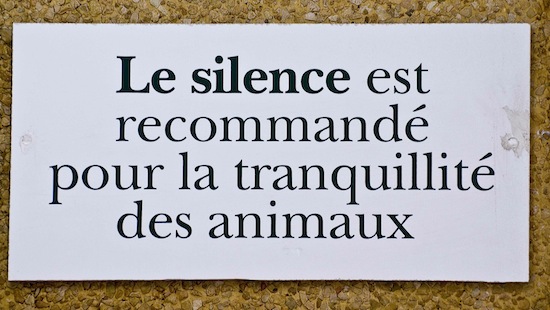

I find a theater seat, but all during the previews everyone is talking as if they’re in their own living rooms.

Finally, the film starts, and it’s worth watching. Christian Bale is such a strange actor. A former boxer, now addicted to crack, he plays the role as a charming, self-destructive fuck-up.

I’m thirsty, but the bottle of Perrier won’t open. I almost break my hand trying to open it. It’s that kind of day.

After the film is over, I ask the guy at the concession stand if he can open it. After a struggle, he does. But don’t I want a cold one? He fetches a key and opens the drinks machine and puts a hand around several until he finds one that’s cold. Oh, how sweet is this gesture!

Having walked a couple of hours, I head home down Blvd. St. Germain. I begin to think about this weird day.

All we wanted was to go out together and have a good time. And all day long it’s been one obstacle after another, an unusual number.

At home, the lights are off and Richard is asleep. So is Marley.

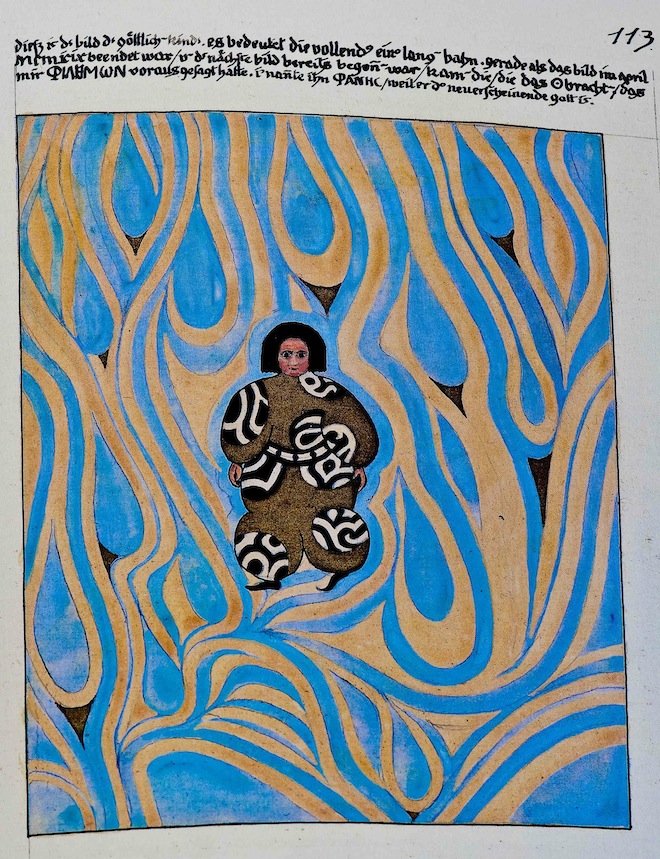

I remember what the psychiatrist, C. G. Jung, used to do when he was baffled by the seemingly insoluble problem of a patient. He would cast their natal horoscope to see where the knots were. Not to predict anything, rather to see what the pattern of stars were at their birth. He did the same for moments and periods of time.

This makes no rational sense whatsoever. But the synchronicity of far and near, (or as the ancients said, “As above, so below”), is perfectly understandable from the perspective of intuition.

I open our astrological calendar, and look at the position of the planets. Oh, of course. It’s the New Moon today, with Sun and Moon in Aries. That’s action. A day when you want to go out and experience life, walk around, go somewhere, spend some money. Or it can be anger. Aries is the warrior, the fighter. Yes, the day had that kind of energy. And what better film to see than The Fighter?

There are two more aspects and they couldn’t be any more difficult. The moon in Aries is square Pluto in Capricorn: Anger. Volatility. Blow-ups. Pluto, the god of the underworld, the dragon.

The moon in Aries is opposite Saturn in Libra: action, anger is fighting with obstacles in the way of keeping one’s balance. I think of Athena, goddess of Libra, and her Medusa shield of snakes. She is usually the one with the cooler head, allowing peace to prevail over war. But with Saturn in Libra, there are obstacles to this peaceful approach.

“Mama said there’d be days like this, there’d be days like this my mama said.” And maybe they’re written in the stars.

[1] The Garden of Plants

[2] Cherry trees

[3] Keep off the Grass

[4] Joker. Mocker.

[5] Goat cheese and zucchini pie (a small tart, really)

04.10.2011

04.10.2011

Chaucer,

Chaucer,  Dante,

Dante,  Jim Jarmusch,

Jim Jarmusch,  Paris,

Paris,  Petit Palais,

Petit Palais,  William Blake,

William Blake,  art,

art,  sexism in

sexism in  Paris Life

Paris Life