As I approach my writing café tonight, a lone clarinetist stands on the sidewalk, blowing a melancholy tune.

Inside, I savor coquilles St. Jacques, and listen. At the tables around me, everyone is French: three women; a couple; two men; a young couple with her parents. All are doing what the French do so well: fine dining and fervent debate. The words I hear are familiar: Charlie. Vincennes. Fear. Murder. Brothers. March. Terrorists. Muslims. Jews. Security. Police. France. Hollande. Obama. U.S.A. Iraq.

This chorus of voices is too multi-phonic to catch more than isolated words, plus, every conversation, though animated, is modulated, as the French do, only for the ears of those at each table. But they are all grappling with the same tangle of threads that Richard and I have been for the past week. What is the larger dimension? If we step back for a broader view, what larger stories, what myths, are being summoned?

Impromptu shrine outside Charlie Hebdo offices, 9 January 2015

Impromptu shrine outside Charlie Hebdo offices, 9 January 2015

There are so many threads, I feel like Ariadne in the labyrinth circling the Minotaur, the monster, trying to untangle the ball of many-colored threads—the clew!—to find the way to the core of the monstrous events of January 7, and January 9 in Paris. On January 7, two hooded men (cobras!) entered the office of a French satirical magazine, Charlie Hebdo, and killed twelve staff members, including four noted cartoonists, and two police officers, with Kalashnikov rifles, shocking the western world as only September 11, 2001, did in recent times.

For the next two days, police in riot gear swarmed France, looking for the trail of the two murderers, Saïd and Chérif Kouachi. On Friday, the eleventh, the two jihadist brothers were found hiding in a printing house in Dammartin en Goële, near Charles de Gaulle airport. At the same time, another terrorist had taken hostages in a kosher supermarket near Porte de Vincennes. When the Kouachi brothers came out of the warehouse firing, they were killed by return fire from the police. Twenty minutes later, Amedy Coulibaly, the hostage taker, was shot, having earlier killed four of his hostages.

Spontaneous demonstration at République, 7 January 2015

Spontaneous demonstration at République, 7 January 2015

On Sunday, January 11, Richard and I headed north from our home in the Latin Quarter to the Unity March at Place de la République. We passed l’Institut du Monde Arabe (the Arab World Institute), and gasped to see on the silver panels (like eyes!) of the Jean Nouvel-designed building, in giant red letters, "Nous Sommes Tous" in Arabic, “Charlie.”

That set the tone for a most moving day. An hour before the march was scheduled to start, the crowd was already thick crossing the Pont Henri IV, on foot and by bicycle. The streets were closed to vehicle traffic for blocks around.

We approached the Bastille, where we intended to meet a group of street artist friends. But a solid wall of policemen and policewomen were diverting everyone in a clockwise direction away from the Bastille, up Boulevard Beaumarchais. We spoke to a few policemen and were struck by the humanity in their faces, the complete absence of aggression in tone, expression and body language. The police in France are in the right relationship to their role, protecting the public, defending, not attacking, as is too often the case in the U.S.

By the time we’d marched three blocks up Blvd. Beaumarchais, there were so many people in the street that when Richard and I let go of each other’s hands so he could snap a few photos, and I glanced away for one second, I lost him in the crowd. In front of us we’d admired the banner carried by two men that said, “Je pense donc je suis Charlie.” I tapped the man on the left on his shoulder and gave him a thumbs up and a “Magnifique.” He grinned, and exclaimed, “C’etait mon idee!” (“It was my idea!”)

Richard called me on my cell: “Where are you?”

“Right behind 'I think therefore I am Charlie.'” He quickly found me.

Everywhere you looked there were “Je suis Charlie" signs, but other signs too: "Islam is innocent of terrorism," "I am Muslim, Terrorism Does Not Represent Me," "Blame Terrorists, Not Muslims," "I am Jewish," "I am a cop," "Respect differences and stand united," "liberté, fraternité, egalité," all implying the same thing: we are all connected, we are all united in empathy with the victims, against violence.

Aside from one sign that pointed a finger of blame—“Quatar finances terrorists”—not a single sign we saw was divisive. There was no shouting, no pushing (well, a little), and from the politicians, no speeches. Just silence, arms interlocked, dignified, a mood of gravitas.

Everyone there was aware of the potential for violence, and most of us were grateful for the dense presence of police and the helicopters overhead. The terrorist alert was at maximum, so the more than 40 political leaders from Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, were filmed on a roped-off side street, TV images of which moved me to tears later that night.

As block by block we surged closer to La Place de la République, it began to feel like a cattle yard. Richard, who has claustrophobia in crowds, needed to peel away onto a side street. I pressed forward for another 30 minutes, until I could no longer move. Enough. I turned onto a side street, rue Charlot, and passed a couple who live in our building, she American, he French, the ones who give the annual Christmas party for everyone in the building. (American warmth, bien sûr.) We greeted each other going in opposite directions.

Turning onto rue de Turenne, I passed a phalanx of police vans, and stopped to phone Richard. Surprise—he was right down the street taking photos. He’d just run into Sylvia Whitman and David Delannet of Shakespeare and Company. Richard waited for me in front of a small church, and we ambled to the Marais for galettes and conversation, returning to the question posed in “A Day of Mourning in Paris,” What turns a young man into a deadly cobra?

Impromptu shrine on Boulevard Richard Lenoir for Ahmed Merabet, a French police officer shot and killed near Charlie Hebdo offices, 9 January 2015

Impromptu shrine on Boulevard Richard Lenoir for Ahmed Merabet, a French police officer shot and killed near Charlie Hebdo offices, 9 January 2015

How to approach the question? At La Maison de la Poesie the other night, a friend and I heard Russell Banks (the author of Affliction, the best novel I know about the wounds inflicted on children by an alcoholic, abusive father) talk about what being a storyteller entails. When he’s telling a story, he’s trying to penetrate the mystery of what it is to be human. And he begins with one character. No one act depends on a single motive. A writer knows that no one does anything for just one reason; as humans we’d like to reduce acts to one reason, but it’s impossible.

And so, it might be illuminating to examine the roots of terrorism by looking at the character of just one of the three men who murdered 12 journalists and staff (cartoonists!) and four Jewish shoppers (marketing for Sabbath, their holy day!), the one about whom we have the most information: Chérif Kouachi.

What do we know about him? Thanks to a fine piece of reporting by the New York Times, we learned a great deal quickly.

That he was the younger of two brothers whose father had died early, and whose mother died in 2004, when Chérif was 12 and Saïd was 14. They were sent to live in a boarding school for orphans and troubled children in the village of Treignac in central France. According to Mohamed Badaoui, a classmate of Saïd’s, Chérif was the more outgoing. Both brothers played soccer. Neither seemed to be religious.

They were Algerian-French in descent, with all that that colonial history implies. The Algerian War of Independence from France was fought relatively recently, from 1954 to 1962. The war was prolonged and bloody, with atrocities on both sides, and left psychic wounds that remain to this day.

(It seems intuitively obvious that the memories of one’s ancestors are in our DNA, and this is now being proven scientifically.)

According to Badaoui, their dream was to move to Paris, and this they did, when Saïd was 20 and Chérif was 18.

The two brothers were raised in France, a country whose values are to some extent foreign to, antagonistic to those in Algeria: colonial vs. colonized; predominantly Christian vs. Muslim; democratic vs. older, more tribal North African.

In France, they were marginalized, lived in block housing on the Périphérique, the edge of Paris, in the Nineteenth Arrondissement, a working-class neighborhood full of Muslim immigrants from former French colonies in North Africa. Muslims make up seven-and-a-half percent of the population of France.

They lived in poverty, where the education provided did not seem to lead to the same job opportunities as more privileged and well-connected Frenchmen, where jobs were hard to find, in a setting and an atmosphere where hope was in short supply.

They encountered open or subtle discrimination, as lower-class, lower-income immigrants tend to do in France, and in most other western countries.

Impromptu shrine outside Charlie Hebdo offices, 9 January 2015

Impromptu shrine outside Charlie Hebdo offices, 9 January 2015

In 2003, after the start of the American Invasion of Iraq, Saïd and Chérif Koachi began attending prayers at a Mosque that no longer exists on rue de Tanger. It was here that the brothers met Farid Benyettou, a 22-year-old Muslim of Algerian descent.

Mr. Benyettou’s sister had been expelled from a Paris secondary school for refusing to remove her niqab. The banning of veils for women in France, which is an aggressively secular society, seemed to many Muslims nothing more than a sign of disrespect for their religion.

Mr. Benyettou taught a group of young men daily for two hours, inviting them to join jihad. Chérif Kouachi was among those, according to the New York Times, “sickened by images of American soldiers humiliating Muslims at the Abu Ghraib prison.” After Abu Ghraib, his doubts vanished, and he began training with assault weapons, gathering with other jihadist young men in Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, and planned a trip in 2005 to fight in Iraq. He was stopped at the border and arrested, with his teacher, Benyettou, and both were sentenced to prison.

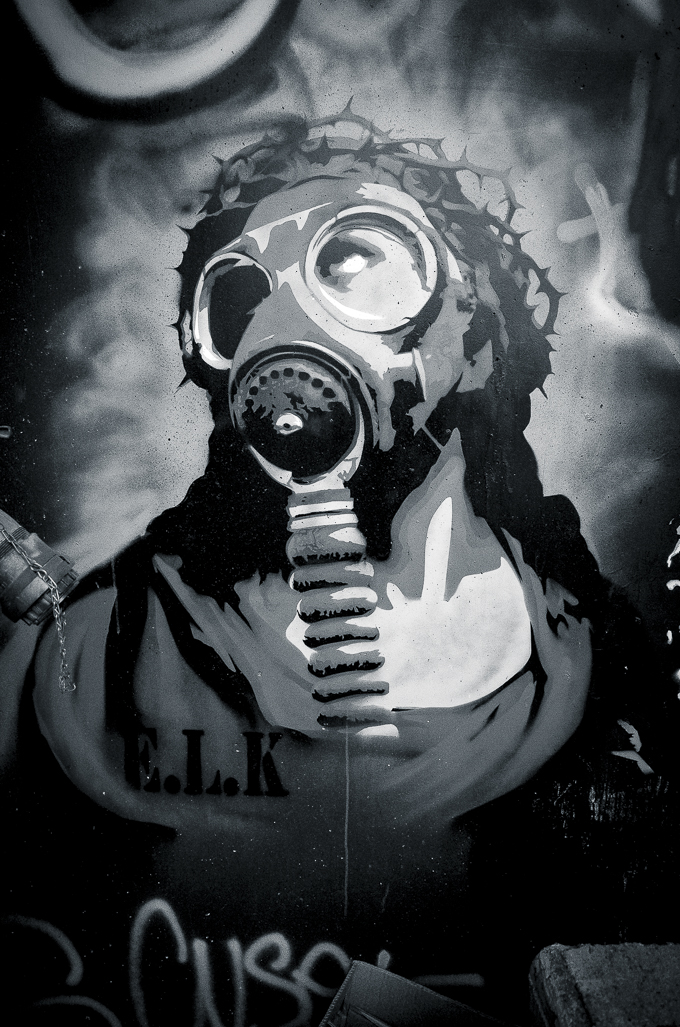

Graffiti at impromptu shrine outside Charlie Hebdo offices, 9 January 2015

Graffiti at impromptu shrine outside Charlie Hebdo offices, 9 January 2015

In this prison, Fleury-Mérogis, 15 miles south of Paris and notorious for its bad conditions and Muslim resentment, Chérif met a radical jihadist, Djamel Beghal, who had trained in one of Osama bin Laden’s camps in Afghanistan. In prison, his radical convictions hardened.

Imagine this as the apex of your ambition, your desire in life: to die a martyr by killing others and yourself so that you can become a bird soul in paradise surrounded by 72 virgins. (And how exactly would that benefit you unless these virgins happened to be female birds?)

This is male heroism completely untethered from the aims of life, the feminine, wisdom, Sophia. It is a loss of tender-hearted humanity, a descent into savagery.

The last time we saw such terrible extremism in the West was in World War II. The German vaterland (father-land) took male efficiency and testosterone-fueled aggression so far from Sophia, the wisdom of life, that perhaps it is no accident that Germans elected Angela Merkel as Chancellor of Germany in 2005, the first woman to hold the office. Women are needed to balance such primitive male warring impulses. It does not seem incidental to me that from the ages of 12 and 14, these brothers lacked a mother. Nor that both brothers kept their jihadist plans secret from their wives, who, apparently, were shocked by the savagery of their husbands’ acts. Nor that these deadly plans were hatched in mosques and prisons without women around to point out the insanity of this perversion of religion.

We need female heads of government around the world. The world is terribly out of balance. Without the feminine aspect given equal power with the male, men lose guidance towards life. If women headed more countries, there would be less war. (Of course, there are exceptions to this perspective among women, but not many.)

And looking beyond the tangled threads in France:

The record of the U.S.A. in Afghanistan. Russia understood the wisdom of withdrawal long before America did.

After 9/11/2001, there was a rush to war in the U.S.A. and Britain, fueled by a cynical stoking of fear for the purpose of greed. The invasion of Iraq was accomplished based on lies about “weapons of mass destruction” to cover the baser motive of greed for oil and money. Cheney and cronies gained billions from nepotistic contracts in Iraq.

Other imperialist western countries, France and Britain among them, rushed to join the U.S. at war in a country on another continent.

U.S. diplomacy failed spectacularly. Neither political leaders at the time, nor military leaders and soldiers, were trained to understand the culture they invaded, neither its tribal allegiances nor its complex religion.

Modern drone warfare wreaks collateral damage on a country’s inhabitants, killing innocent women, children, and men who are not affiliated with jihadism.

American torture, humiliation, and wrongful, illegal imprisonment further inflamed Muslim jihadist rage. Waterboarding, Guantanamo, Abu Ghraib.

War creates an endless tribal cycle of vengeance. Of attack and counter-attack. If a man’s relatives, home, village, country are devastated by a foreign power, and he lacks money, power, artillery, but is filled with the rage to revenge himself, jihadist extremism might seem to be the only path.

If that path is legitimized by so-called religious leaders, their teachings provide a purpose for testosterone-driven lost young men, and an outlet for resentment at being treated as second-class citizens by the western world.

And then there is the anti-Semitic element in all this. Chérif Kouachi talked obsessively about attacking Jewish shops and Jews in the street. Targeting a kosher market was no accident. Was Israel’s war on Palestinians an element in this anti-Semitism?

The rage of jihadists seems to be aimed at the countries that are most imperialistic at the present: the U.S.A., France, Britain, and Israel. How swiftly the victims of one vast crime—Germany attempting to eradicate the Jews—become the bullies of another—Israel crushing Palestine. The terrorists demolishing the twin towers, followed by the U.S. invading Iraq. Where is the pause for reflection, for understanding, for action born of wisdom?

Finally, free speech. How far can it go when it involves mocking what is sacred to between twenty and twenty-five percent of the people on earth?

And where, you might ask, in all this discussion of the jihadist terrorists is my empathy for the seventeen murdered victims? It is deep and ongoing. In every conversation we’ve heard or read about in Paris, the sympathy for the victims is huge.

The central issue of our times is the monster in the center of the labyrinth. It is tempting to see him as a jihadist terrorist. But perhaps he is any religious fundamentalist, whether he appears as a Muslim terrorist in Paris or NYC; Christian fundamentalists in the U.S.A; American right-wing politicians lying about their reasons for going to war; Jewish fundamentalists in Israel, and Muslim terrorists in Palestine, murdering each other; Christian and Muslim fundamentalists in Nigeria terrorizing each other; Buddhist terrorists in Myanmar murdering Muslims. He is the one we need to try to understand. He is the least educated, the most medieval in his thinking, the most resentful, rageful and dangerous, the most violent in his actions.

Impromptu shrine outside Charlie Hebdo offices, 9 January 2015

Impromptu shrine outside Charlie Hebdo offices, 9 January 2015

In the myth of Ariadne and the Minotaur, it bears remembering that the bull man, Asterius, is Ariadne’s half-brother, no stranger. She must follow the clew to the core of the mystery, to free both the Minotaur and his sacrificial victims. Only wisdom, understanding can take us there.

In a sense, the Arab world is Sleeping Beauty. If we go back centuries—what learning, what intellectual genius and innovation!—in art, in science, in mathematics.

During the Crusades, when Christianity dominated in Europe, what happened to Arabic learning? What happened to the lively intellect, the scientific questioning, the wisdom? How did the intellectual tradition harden into reactionary dogma?

And what is the story between Christianity and Judaism? The myth of warring brothers; an antagonistic relationship of 2,000 years. You have only to look at caricatures of Jews, from low-level bigotry to literature, from the ghettos of Europe, the banning of Jews from many professions to the demonizing during the rise of Nazism, which culminated in the horror of Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen.

French street artist C215 gives away hundreds of stencils outside the 13th Arrondissement city hall, 11 January 2015

French street artist C215 gives away hundreds of stencils outside the 13th Arrondissement city hall, 11 January 2015

In the drama which unfolded in Paris during the last week, we saw three marginalized groups, the so-called “Muslim” French-Algerian jihadists, the Kouachi brothers; the four Jewish victims in the supermarket at Vincennes; and the African-French hostage taker, Amedy Coulibaly, born in France to parents from Mali.

Many of France’s Catholic majority of between fifty-one and eighty-eight percent of the population, and its ever-growing number of agnostics and atheists, along with Muslims, Jews, French-Africans, and many from other continents and countries, between one and two million people strong, all marched in Paris on Sunday, January 11, to the Place de la République. The overwhelming spirit was one of unity; another two million people marched in other French cities.

I’ll go out on a fragile limb and say, to me it looks like a new paradigm, a realization that we are lost if we continue to slaughter one another in the name of religion, fanaticism, revenge, greed for money and oil. The planet will not survive.

What is out of balance is the balance between masculine and feminine values. And the root of this is spiritual vision. If God is pictured as a man, solely a male, it doesn’t matter how far you go from that primary vision: you can go as far as doubting, or denying, agnosticism or atheism, but you’re still on the masculine track.

If your vision, spiritual and/or secular, can imagine a world where female and male values share space, that means a world in which war is a last resort. A world which cannot move too far beyond what’s healthy for humans, animals, the earth itself. A world in which we pay attention to visible signs like increasing cancer rates, and the increasingly alarming weather, disappearing animal species, and invisible signs like dreams, anxiety and dread.

If more women were allowed to lead or at least participate equally in governance, the sanctity of life would be the first consideration, not power.

To clarify, all of us humans are androgynous creatures, with feminine sides (life and relationships) and masculine sides (power and work). Just as women are robbed of half of life if they are prevented from working, from circulating freely and independently, from self-governance, by their fathers, brothers, husbands, culture or religion, so men rob others of life if they blindly follow the will to power and war, as Cheney and Bush did in 2003 in invading Iraq, as the two Kouachi brothers did in murdering twelve staff and policemen at Charlie Hebdo, and as Amedy Coulibaly did in murdering four Jewish men in a supermarket in Paris. They are two sides of the same phenomenon, the will to power divorced from the feminine sense of the sanctity of life.

Sanctity: the sacred. Life doesn’t care what you believe in: whether it’s Mohammed, Christ, Jehovah, Shiva, Buddha, No One, or You-don’t-know-Who. Life is sacred no matter what you believe in, or don’t. And it has its male spirits and its female spirits.

When I did my own vision quest, I took apart all the parts of my psyche. And I discovered that there were twelve parts, and I gave them names. Later I discovered that these twelve parts had already been named long ago by the ancient Greeks, the names of their gods and goddesses. These re-emerging male and female divinities represent to me the beginning of a crumbling of monotheism, a reawakening to the ancient truth that polytheism is what is needed for harmony and balance.

Impromptu shrine outside Charlie Hebdo offices, 9 January 2015

Impromptu shrine outside Charlie Hebdo offices, 9 January 2015

The gods and goddesses are no longer “out there,” up in the sky, beyond us, separate from us. Instead, they are the very structure of our psyches, the archetypes that make up our deep souls, and who speak to us in dreams. If we listen, we can begin to live in harmony. If we deny or ignore them, we are troubled by addictions, disturbed sleep, raging anger or greed or depression or loneliness and all the other maladies of modern life out of balance. We can heal ourselves, and the world, by listening to these innate sacred voices in ourselves, which are part of all of us.

We’re entering into Nietzsche territory here: What did this profoundly spiritual philosopher mean by "God is dead?" His sense of the old Homeric Greek gods and goddesses was vivid. He clearly meant the punitive monotheistic god, not the array of spirits Homer dramatizes as present in all human activity. Jung territory: all the archetypes of the unconscious are alive, and they are sacred. The gods are reawakening.

It will, of course, take hundreds of years. But it’s beginning. There is a way out of the labyrinth.

03.8.2015

03.8.2015  Street art © 2015 by E.L.K.

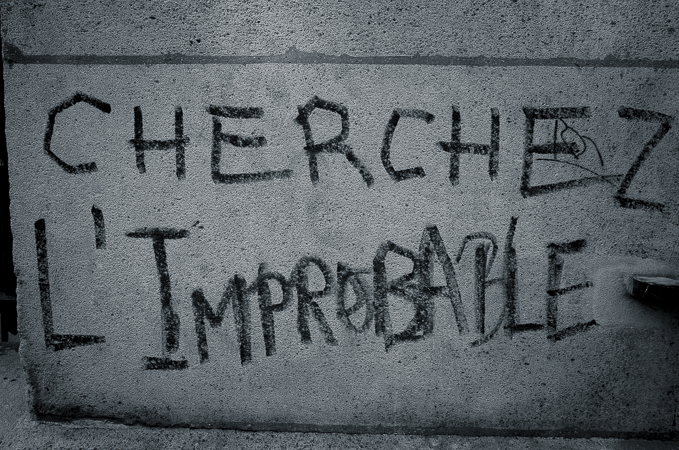

Street art © 2015 by E.L.K.  Street art © 2015 by PopEye

Street art © 2015 by PopEye

Street art © 2015 by Fred le Chevalier

Street art © 2015 by Fred le Chevalier

Paris,

Paris,  cafes,

cafes,  cigarette smoking,

cigarette smoking,  magic,

magic,  synchronicity,

synchronicity,  writing in

writing in  Paris Life

Paris Life