Le Dernier Chevalier de Paris?

06.21.2013

06.21.2013

Although the first morning of summer dawned gray, drizzly and damp, we were nonetheless in a great mood, standing at nine a.m. on a street corner in the 20th arrondissement, the vital, hilly artist’s district called Belleville, waiting for one of our favorite street artists, the gentle knight, Fred Le Chevalier.

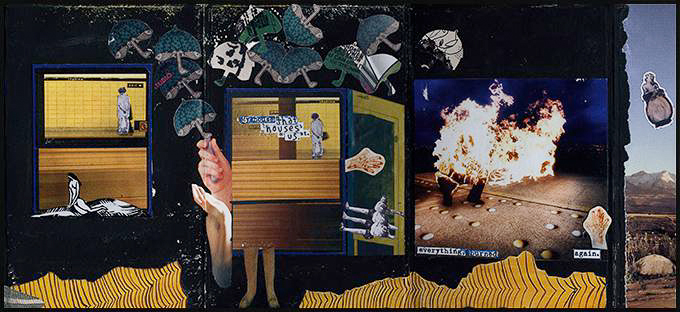

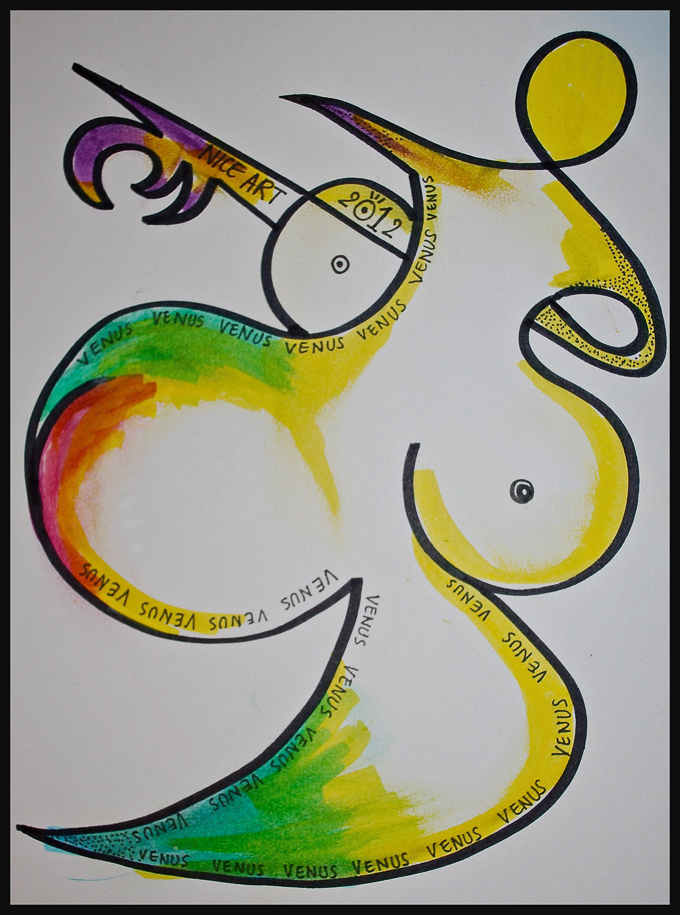

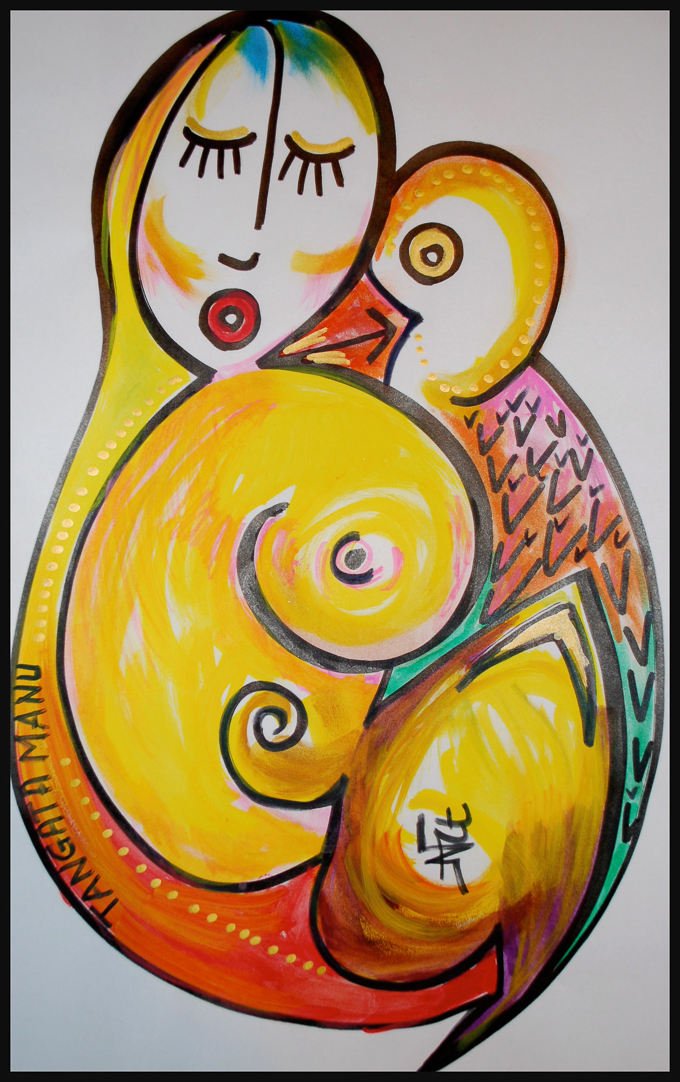

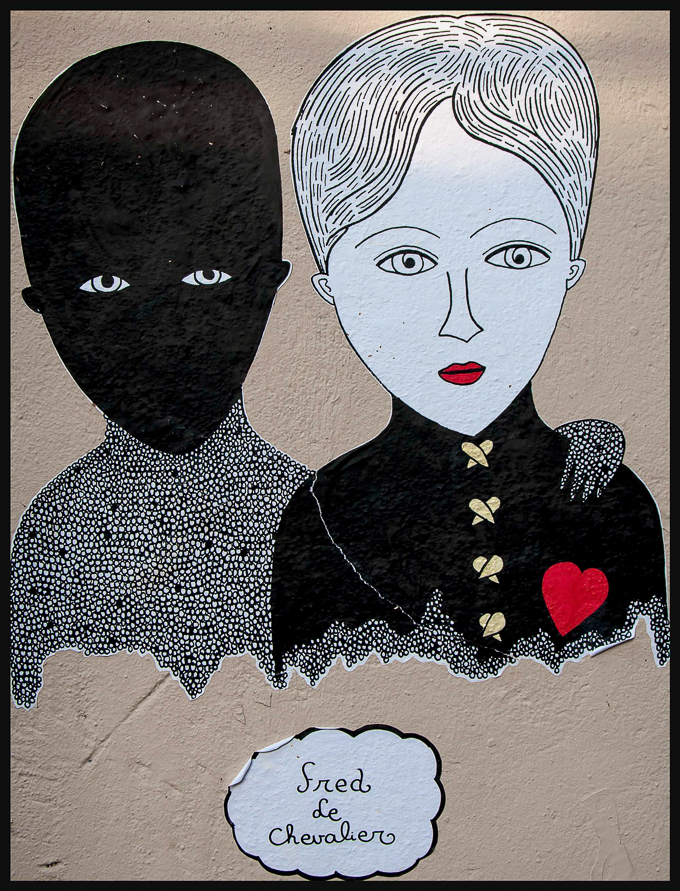

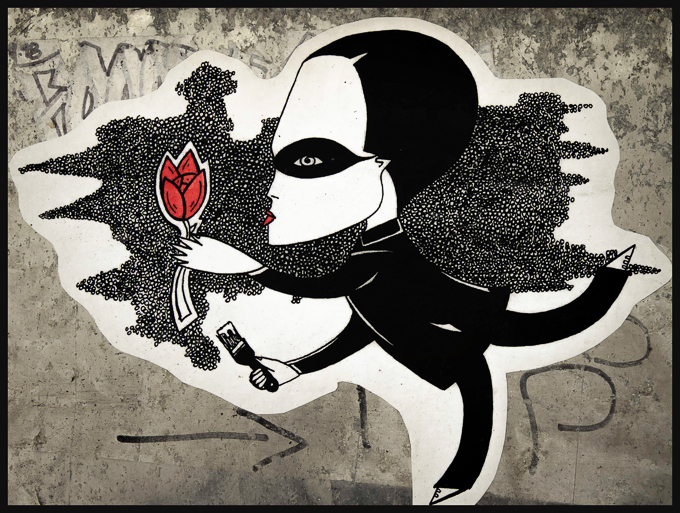

We'd been captivated by Fred's simple but eloquent work since we first arrived in Paris two-and-a-half years ago, and have used it on occasion to illustrate our essays. Small black and white stencils (with red, green or yellow accents) of archetypal males and females, sometimes kings and queens, often pictured with totem animals like owls, cats, foxes, wolves, and hedgehogs, sometimes with a single line of poetic prose to illuminate, but not explain.

The work was clear, detailed and precise, but didn’t look schooled; it had a naïve quality, both in the humans (with their guitar-pick-shaped heads) and animals it depicted and in its style. As we met more and more people in the street art community, we discovered that Fred had detractors, people who felt all street art should primarily be political, who attacked the work’s very simplicity and gentleness, who felt that Fred, although he only began working shortly before we arrived in Paris, was too popular, too soft-edged.

It was an argument we’d heard before in our political lives, like listening to the folks who followed Malcolm dissing the folks who followed Martin, not recognizing that ALL the political activity was part of a continuum, all valid, all necessary, all appealing to its own adherents under a broader umbrella. Street art itself is a radical act, illegal, but a gift to the community.

And Fred’s mythopoetic work, under the nom de rue “Le Chevalier,” was political as well. He was taking a stand for chivalry, for the Arthurian knights, for the troubadours, for the Celtic romantic tradition that was born in France, and still undergirds the best of French relationships. His almond-eyed characters came in all shapes and colors and persuasions—anyone is free to love anyone else in Fred’s universe—reflecting an egalitarian world of large virtues like truth, and love, and marriage equality. “Love,” he captioned one stencil, “is never dirty.”

As we followed his career, his stencils grew larger and larger, occupying more and more Paris wall space; there are well over three thousand paste-ups of hundreds of drawings. His output was prodigious, an unfettered orgy of joy in art.

And we began to see Fred’s people on buttons, handbags and T-shirts. A populist artist was emerging. From various articles in the real-world and virtual press, we learned that Fred is from Angouleme, a small town in southwestern France, that he was self-taught (though his father was also an artist), that one of his primary street art influences was the seminal Ernest Pignon Ernest, and that his ambition was to give up his day job and eventually make a living solely from his art.

Part of what moved him was that street art was egalitarian and free. “Putting my drawings on the walls of the city is the only way to share and to talk with all the people.” As he told the Brazilian journalist Fernanda Hinke-Schweichler, “Punk music has the same spirit of being able to express yourself freely without being a musician.”

Eventually, we met him, at one of his public paste-ups near a small art gallery in the tenth arrondissement, and saw him again at a second opening (at which he sold everything in under an hour), and at a few small fairs he had organized at which he and other artists and artisans could sell their arts and crafts. We found the forty-something but ageless artist to be as gentle and open as his characters, elfin, large-eyed, long-lashed and guileless. He wore on his sleeve, not his heart, but tattoos of his own characters, done by a friend. This was a man committed to his art and his philosophy, wearing the statement permanently on his own body.

Recently, when he was asked by an important French publisher to do a book (coming out this September), he asked Paris Play if he could use some of our photographs, particularly of his early work. He knew we had been chronicling his work in photographs, and had amassed well over two hundred. He said he had some grab shots he had taken over the years, but knew that ours were high-quality efforts to document the street art scene.

And the work, of course, is ephemeral. He uses stencils precisely because they do decay, and disappear over time. “If people don’t like it on the wall,” he told us, “it’s not as if I paint-bombed; it will wash away in time.”

So, two days before the first day of summer, we spent a delightful hour with Fred drinking Badoit in front of our computer, as he flipped through the photos in Adobe Lightroom, choosing which he wanted for possible inclusion in the book, and telling stories in his melodic voice as he went. “This one is two friends of mine who were getting married…. This one has a skull in it to represent death, but I always see that there is life in death…. I don’t know why this one has a key, but I liked it…. Yes, this is an umbrella, but it could be a UFO.”

After he left, leaving us with a small serigraph print of one of his works, we got to work processing the couple of dozen pictures he needed. In the process, we decided to post his drawing of a man on a bench in the rain with a potted mushroom that was also an umbrella and maybe a UFO as our daily photo on Paris Play’s Facebook page. It was particularly pertinent, since Paris had been through three days of thunderstorms, with no end in sight to winter.

When Fred saw our Facebook post, he e-mailed us: Meet me Friday morning in Belleville and I’ll put up some work for you.

Absolutely!

So we went to the appointed street, and at ten minutes after nine, received a text from Fred: Oooops, I mixed up the names of the streets I was going to work on. Can you get to the church of Notre-Dame de la Croix instead?

No problem. A quick ten-minute hike from Belleville to Menilmontant, the other exciting working-class and artists’ district. Taken together, Belleville and Menilmontant are to street art what Montmartre or Montparnasse were to the Paris artists of a hundred years ago. Picasso’s rebel spirit lurks, spray can in hand.

Finally, we met up in a lull between storms and Fred, his two long extension handles looking like Quixotic lances, led the way to the first wall, at Avenue Jean Aicard, a popular street art spot at the corner of rue Oberkampf. As he pasted up his first work, of two turbaned men, one black, one white, following a candle they carried, much like Diogenes, he was interrupted three times by fans who stopped to ask him questions or praise his work. He graciously took the time to talk to each.

The first stencil finished, he moved to another large empty wall across avenue Acaird, the site of countless stencils, paintings, stickers, etc. that had come and gone since street art prehistory, now-missing work that we had photographed over the last two-and-a-half years.

"This one is a surprise for you," Fred said with a shy smile.

As he began unrolling the first panel against the rough plastered wall, using a bristled brush on a telescoping handle, we recognized it immediately; the man on a bench under an umbrella or mushroom that could be a UFO, protecting himself and a small animal from the rain that fell like tears all around them. A giant version of the photo-of-the-day on Paris Play's Facebook page.

As Fred unrolled and pasted his panels (each about 2.5 meters tall), two more passersby stopped to watch intently. Richard continued snapping pictures.

After a minute, one man, wearing a New York Yankees baseball cap, a brown bomber jacket and dark sneakers approached us, peered up at Fred’s work, and spoke in French. Richard responded with his usual, "Je suis desolée. Je ne parle pas bien Français." (Sorry, I don't speak French very well.)

"Alors," the man responded, "vous êtes un journaliste étranger." (So, you are a foreign journalist.)

"Oui," Richard replied.

The man moved on to Fred, removing a small, thin case from his plaid shirt pocket. He held it open, and Fred gulped.

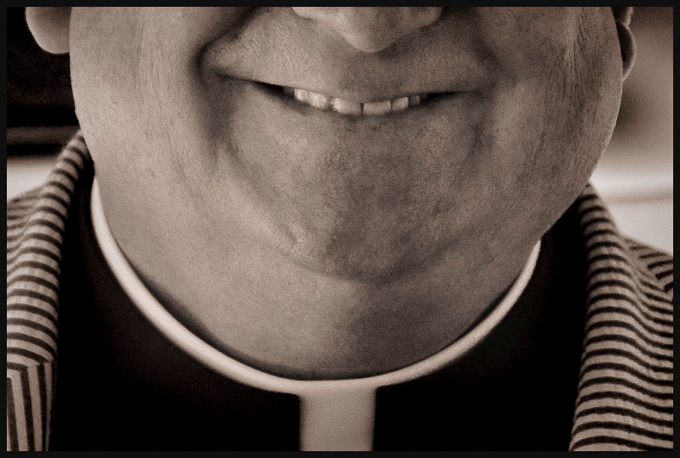

It is illegal in France to show the face of an undercover officer

It is illegal in France to show the face of an undercover officer

The man then turned to Richard. "Pas de photos pour cinq minutes, s’il vous plait." (Stop shooting for five minutes, please.) “Oui.”

He removed a small notebook from his pocket, and wrote down Fred's answers to his questions. The basics: name, address, age, phone number.

They spoke quietly for less than five minutes, then the man walked off.

Fred looked poleaxed. "Very bad news," he said, with characteristic calm.

The man, he said, happened to be Paris' chief detective in charge of stopping illegal street art. Fred explained that, while the various (20) neighborhood city halls can allow certain artists to work on approved walls in their arrondissements, and the owners of buildings can allow artists' work on their property, the City of Paris has jurisdiction over stopping unpermitted wall art.

After taking Fred's information, and explaining to him that the fine could be anything from 35 to 3,500 euros, he promised he'd be in touch about the present violation. No matter what the fine, however, Fred was now on notice: He would be arrested and/or fined if he posted another stencil within the city limits, that part of Paris within the Périphérique, the freeway that rings the city.

We remarked at how civil the process had been. A subdued conversation on a street corner. Fred gave his information, but could easily have lied about any of it, since the detective didn't even ask for ID. Fred shrugged. "Why lie?" His chivalrous characters gathered around him. This is a man with a sense of ethics.

And this is an artist. He continued putting up the final panels of the stencil. Why leave an unfinished work on the wall? We discussed the fine, and taking up an online collection to help him pay it. He smiled, but raising only one corner of his mouth, gave a Gallic shrug, and continued pasting.

His mobile phone rang within the next ten minutes. It was the detective. Yes, this was an illegal wall posting, the local city hall had confirmed that. The fine would be up to five hundred euros. Yessir. He hung up and continued. “He said they knew my work, and my street name, but now they have my true name, and address.”

“Not work again in Paris? What will you do?”

“There are the suburbs. Pantin,” he allowed, sadly.

His phone rang again. He ignored the call, and finished the final panel.

He picked up his paste pot, brushes, and rolled-up stencils, and we set off to a nearby café to discuss the calamitous turn the day had taken.

But wait. His phone rang again, and he answered it.

The detective again. The fine was now eight hundred euros, he told Fred, because he had continued pasting after the warning. While the detective was nowhere in sight, Fred was under surveillance. He would not be fined this time, the detective said, if he agreed to take the work back down, but he was still admonished against putting up anything else illegal in Paris. If he did, they would fine him thousands for each piece.

Fred turned back to the wall, which now loomed like the bulwark of a medieval castle. Slowly, he peeled off the last panel, which was still wet, letting it drift to the sidewalk in a crumpled pile. He straightened it out and let it lie.

He continued with the other panels, but since they were drier, he had to rip each one, pulling smaller and smaller pieces from the wall, destroying the man on the bench, the animal he sheltered. He grunted and crumpled the intact panel, shoving it with the other scraps into the nearby city trash bag.

It began to rain.

(Fred let us go on shooting pictures, but later texted, “Please don't publish the pictures where I pulled off my paste-up. I don’t think I could look at them.” His perspective on events is in French on his blog.)

When he was done, we offered again to buy coffee.

“No,” he said. “I think I need to be alone. I will just walk home. I hope you understand.”

He turned, bucket and stencils under his arm, lances held upright, and walked off into the Paris drizzle.

All artwork depicted in this issue is copyright 2013 by Fred Le Chevalier. Text (c) 2013 by Kaaren Kitchell and Paris Play; photographs (c) 2013 by Richard Beban and Paris Play.