After the saddest year of my life (but was it, really? I ask myself, and answer, Yes, it was), I was surprised tonight to feel the joy returning. That old version of joy, of life as overflowing abundance. First, Richard and I went away for four days to Amsterdam. More on that in a later post.

A leisurely break, a honeymoon of sorts, followed by fresh energy for each of us in our work. The day after we returned to Paris, I sent off a chapter of my novel to a literary magazine. It’s strange, the shift, a new kind of detachment from the results of submitting work, a new kind of unwavering resolve.

I’ve had many professions, U.C. Berkeley language lab, tutor for the blind, model, cook on a schooner, waitress, bookseller in Sausalito, Cambridge and NYC, real estate agent, on-the-road art dealer, teacher of Greek myth.

As an art dealer, I learned two things: finding the right gatekeeper is a simple matter of love—the artist’s sensibility resonating with that of the dealer/agent/buyer. And the value of the best art often takes people the longest to see.

My favorite of the artists I carried was invisible for a full year to everyone to whom I showed paintings, until, one day in my suite at Los Angeles' Chateau Marmont Hotel, a couple of top collectors walked in and flipped over this artist’s work. A few minutes later, they were in the hallway conferring, and minutes later, writing a big fat check. No accident that they did not need my vote of confidence in their taste (as many collectors did).

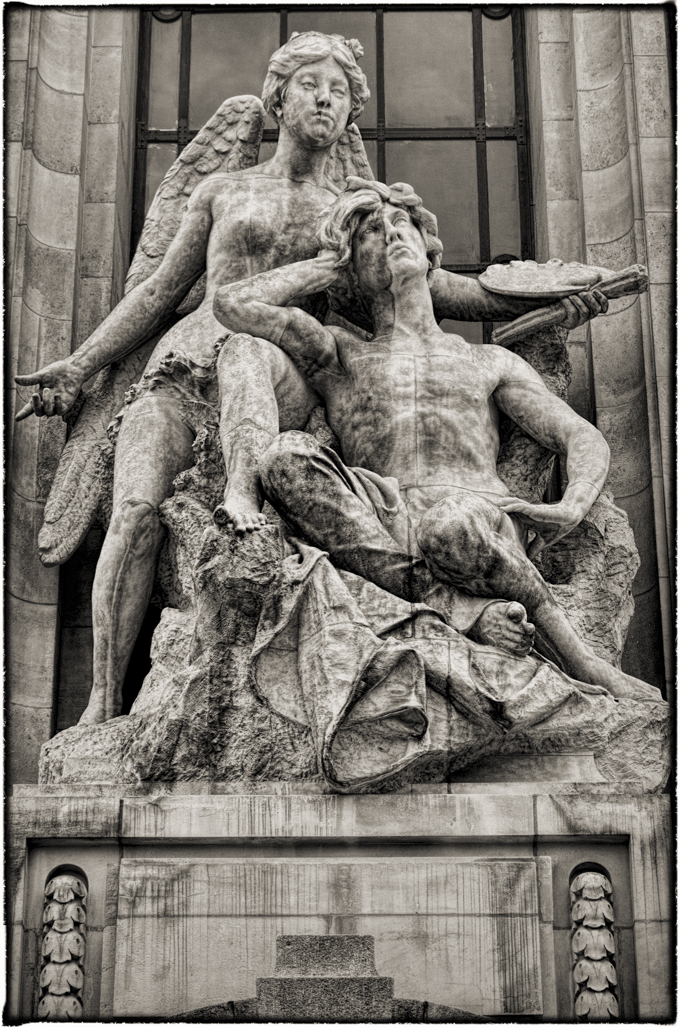

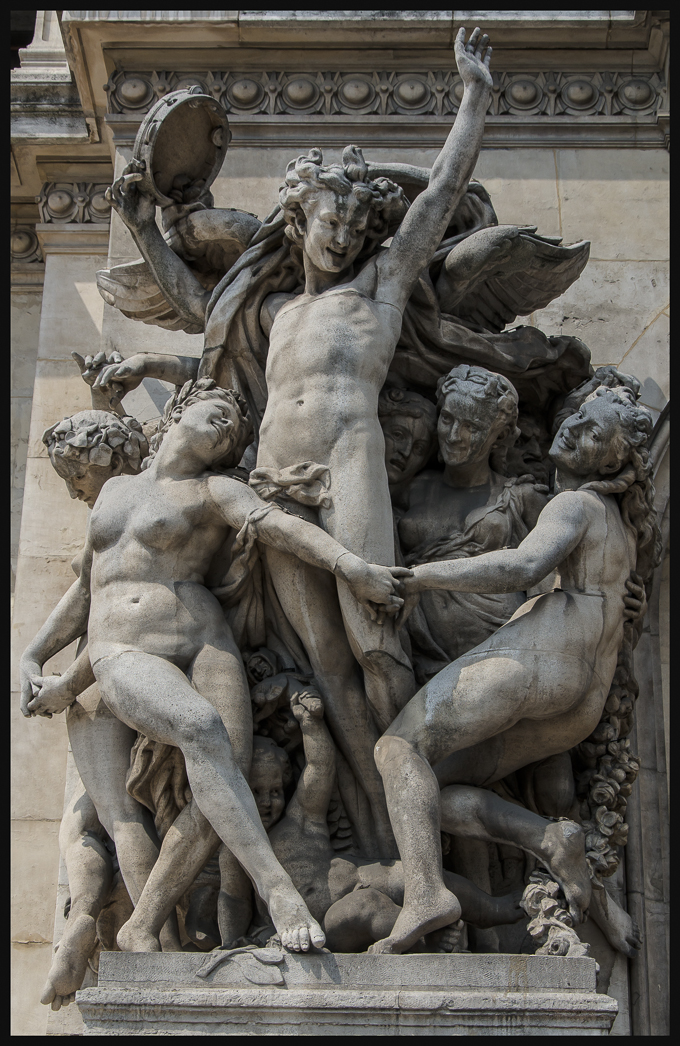

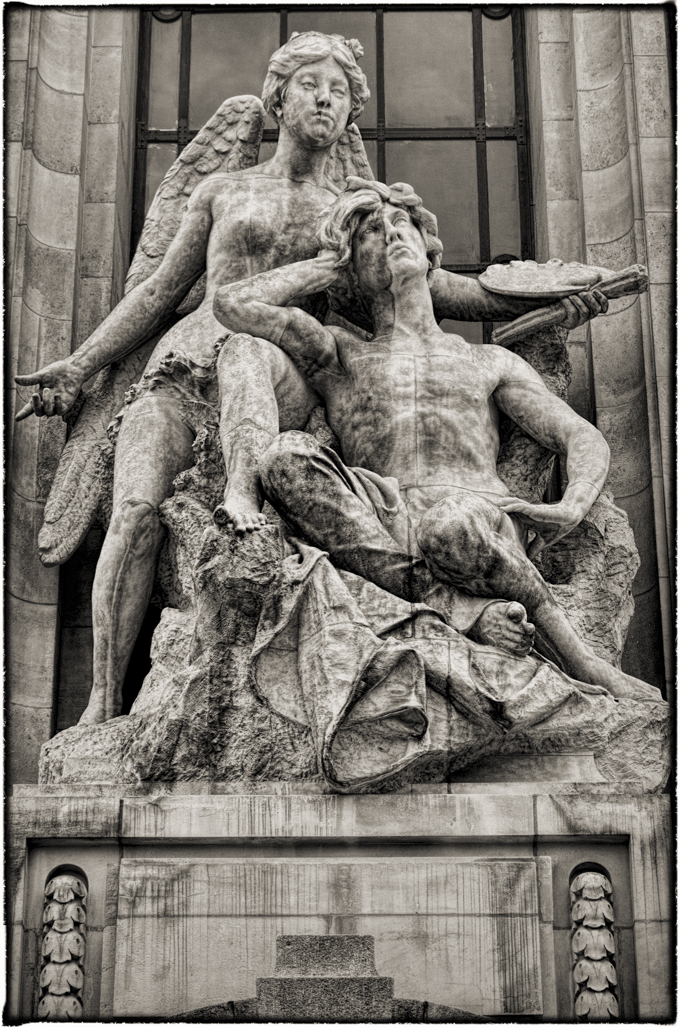

The structure of my novel is unorthodox, but the characters will not allow me to change it. Last night, after two-and-a-half hours in my favorite café, doing final editing and finishing chapter nine, the young couple next to me and I struck up a conversation. They asked me what I was writing. I told them (very briefly), and added (since they were Greek) that its structure was based on Greek myth. And then the woman and I began to talk about what is so wonderful about Greek mythology. (After a couple of millennia of strict monotheism in Greece, I am always surprised—delighted!—to encounter a Greek person, an engineer, no less, who loves Greek myth.) We agreed on three things: it represents divinity that is both male and female; these gods and goddesses are like human characters, with all their strengths and flaws; and it is essentially stories. I left the café feeling I'd been given a message, a gift.

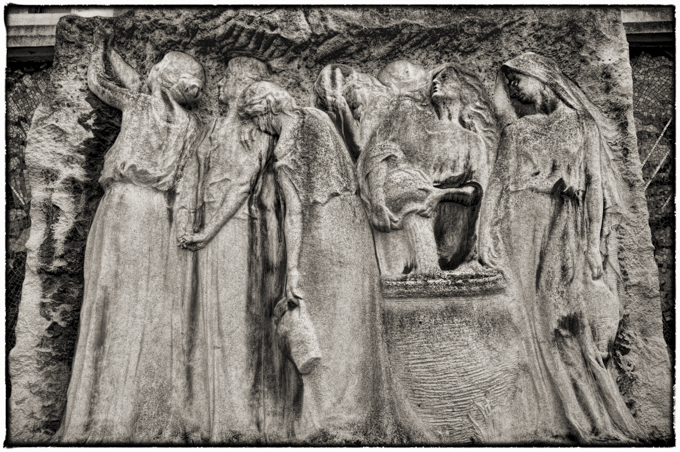

And then tonight! Yow. Hélène Cixous read from her latest book, Twists and Turns in the Heart’s Antarctic, at Shakespeare and Company bookstore. First, her translator, Beverley Bie Brahic, read an English translation; then Cixous followed with the original in French. The text was poetic fiction, an essay, an epic, a Greek myth, about a daughter named Hélène, a brother, O., with whom she has a murderous relationship, and their 100-year-old mother, Eve. The images were closely observed, intimate; the metaphor, of Euridice (the mother) following Orpheus (the daughter/writer) shakily down some stairs. Stunning writing.

And this was peculiar, an image that sounded wonderful in English, the mother’s recent bond with a teddy bear, sounded slightly sentimental in French. In addition to the gorgeous writing, I felt a longing to live closer to my mother, the pain of being far from home soil, a pang of admiration-envy of my two sisters and brother who live so close to her. (For everything, there is a price, and this is the price for me of living in Paris.)

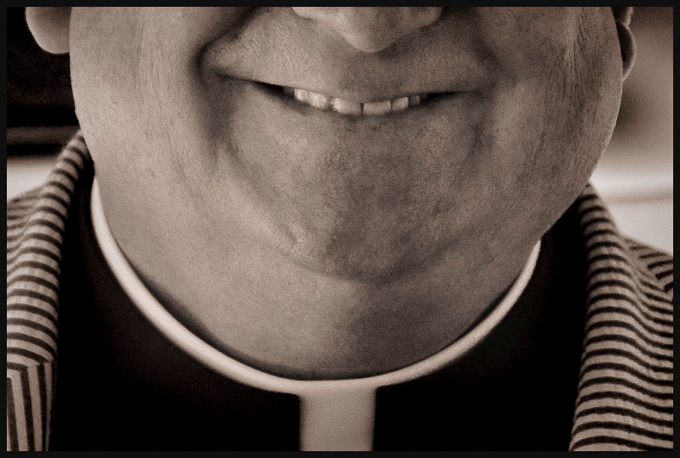

I have loved Hélène Cixous’s work for years. I drew closer, standing in the doorway, as H. C. answered questions after the reading. A beautiful face, big ears, long nose, Algerian-French, German Ashkenazi Jewish on her mother’s side, Pied-Noir Sephardic Jewish on her father’s. A fez cap, gray-green cardigan and scarf over a black sweater. A relaxed and delicate face. Nefertiti eyeliner. She looked a bit like Nefertiti.

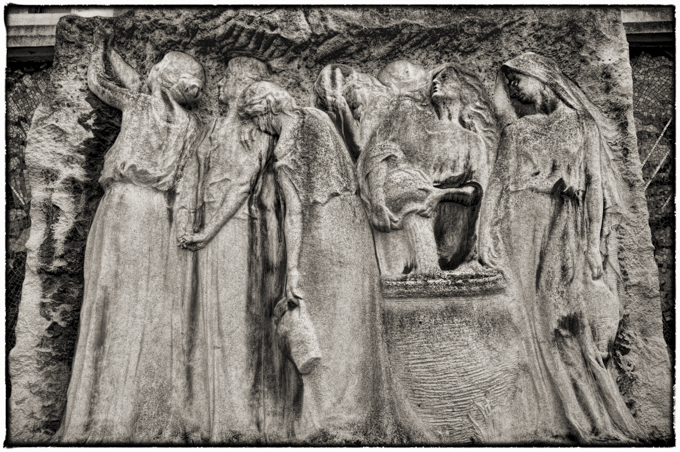

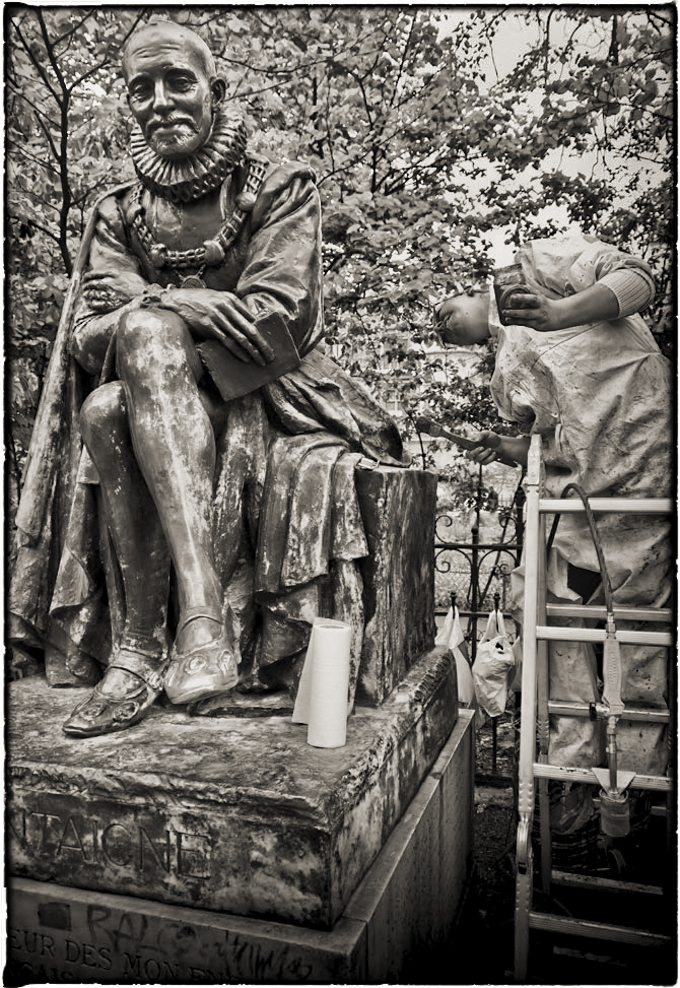

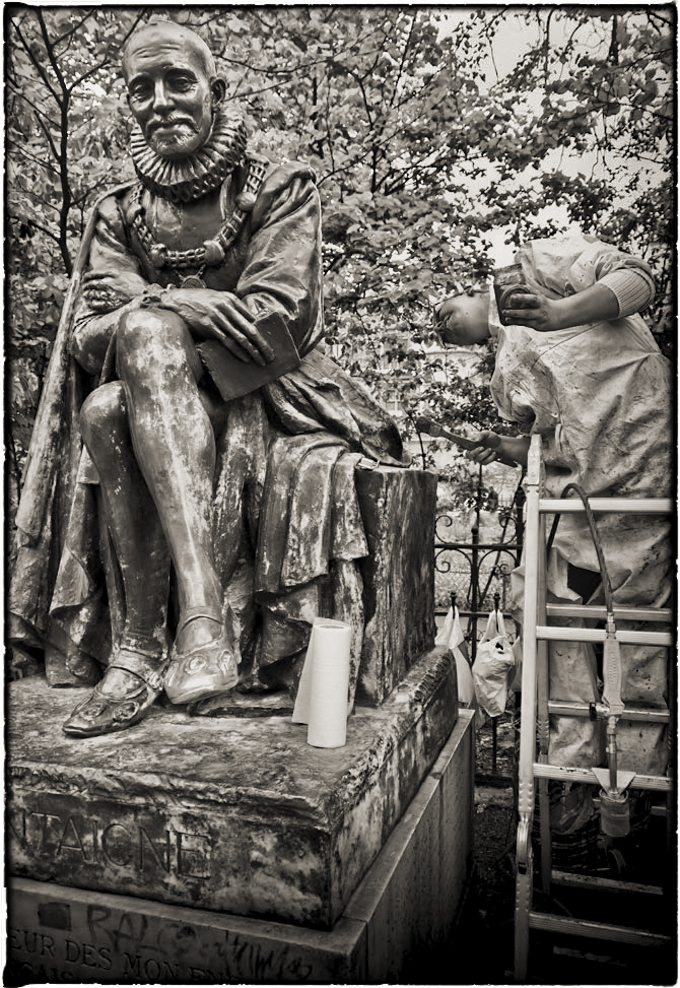

She could not “enter” France for years, found the French too bourgeois, “carpeted,” until she found the door. That door was the tower of the small castle that had once belonged to the great essayist, Montaigne, in the town of the same name. His writing room was about the size of the room in which we were gathered. A view from the small windows of vastness, reminding her of Goethe’s view in Strasbourg. She felt the imprint of the books that had once surrounded him, though they are long gone.

She now goes back to visit Montaigne’s tower once a year for inspiration. Of course, she says, you have to have read all of Montaigne’s essays for it to mean anything. Important things happened in this tower where he wrote. Kings visited the writer there, among them, King Henri IV, the first Protestant king of France. Henri IV, like Nelson Mandela, was a mediator, mediating between the Protestants and Catholics.

In response to a question about why she so often used the first person in her writing, Cixous said, the self is multiple, legion. (Yes! as are the forms of the divine, which is no longer entirely “out there,” or “up there,” but envisioned now as inside us, aspects of the collective unconscious.)

The translator discussed a French word haimé, a word Cixous invented by joining haïr, "to hate," to aimer, "to love." She struggled to find a graceful equivalent in English, and settled for "hateloved."

I asked Alex to save me a copy of Twists and Turns, and bolted out of Shakespeare and into the street, too happy to wait in line. I called our favorite restaurant to see if they had a table for one. “Oui, Karine!” said David. Had hareng with potatoes and carrots, and warm goat’s cheese on tiny pieces of toast. Then as the restaurant filled with no one but French-speaking diners who were spilling over with exuberance tonight, I left to walk to my (second-)fave café to write this letter to you.

09.3.2017

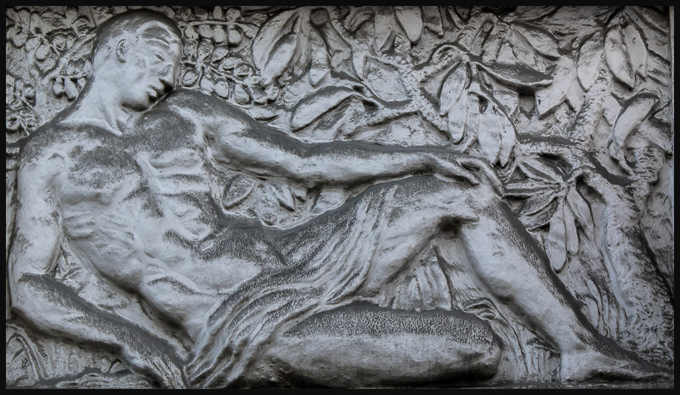

09.3.2017  iPhone photo by Kaaren Kitchell

iPhone photo by Kaaren Kitchell