Yes, he said, yes, he said yes!

We were at dinner at Anahuacalli, our favorite Mexican restaurant in Paris, and he asked me what I wanted for my birthday this year.

A cat! I said.

Okay.

Seriously? You mean it?

Sure. If that’s what you really want. It's your birthday.

We’ve been having a certain dialogue for two years, since Marley died in July 2013. Still grieving, we both agreed that no cat could ever replace our white and gold wedding cake cat. But then I started yearning for, not a replacement, but a Marley brother or sister.

But we want to travel, Richard said, that's one reason we're in Europe. Although… if a cat came to our door the way Marley did in Venice in 1997 and asked to join this family, I’d say yes.

But what cat can wander in through our Paris courtyard, unlock the door to the building and find his way to the fifth floor and knock?

Right, said Richard.

We stopped at our veterinarian’s on Blvd. Saint-Germain for the first time since that summer, to ask if he knew any cats who needed a home.

Doctor McCarthy (who revealed to us once that he was really a cat) wasn’t in, but in the waiting room, a woman in army fatigues with a cocker spaniel suggested we go to the SPA weekend offering at Bastille that weekend, a once-a-year event (by the French equivalent of the SPCA). What timing! What a stroke of luck!

Saturday, we walked over two Seine bridges the twenty minutes to Place Bastille to find a temporary exhibition hall set up under white tents. The canvas cages, with plexiglas windows, were set cheek-by-jowl on top of rows of tables, the cats hunched inside. From the next room, came a staccato cacophony of dogs. We walked through the rows. The first cat I saw was a white beauty who looked like Marley. But no, we couldn’t duplicate him—why even try?

We looked at tiger-striped and calico cats, and various-colored kitten siblings. But the kittens were all sick with coryza, a common shelter cold that comes from close living with other cats, which can be serious.

We chose three cats who appealed to us. But petting them, you could see that they weren’t that affectionate. We returned to the white cat. He’d been adopted two minutes before. I offered to give the woman adopting my card in case the cat wasn’t compatible with a cat she had at home. Oh, no, she said, she would never give up a cat once adopted. Bien sûr, neither would we.

We decided to come back earlier the next day, since a new batch of chats et chiens was arriving. Sunday morning we felt lazy, didn’t want to get out of bed.

Let’s just hop in a cab and go over there and see, Richard said. And so we did. We had a plan. He would start at one end, and I at the other. We each noted a cat that appealed to us, then checked out each other’s choice. No, no. Then went back to look at a tortoiseshell female, three years old, a bomb-shell beauty, with black, red and white patches.

I had the thought that she was like our friend Edith who recently died, who only wore black, red and white. Her papers said she could live in either a pavillon (a house with grounds) or appartement, but advised she needed to be the sole cat in the place, and that we shouldn’t have a child or dog.

I unzipped the cage and cautiously held out my hand. The cat, Jade, came over and lowered her head, asking to be petted. She was sweet and câlin as the French say. A cuddler.

What do you think, Richard?

He put his hand in her cage and she moseyed over to him for more petting.

We asked the woman in the orange vest if we could hold her. Yes, she said, and turned the cage around to unzip and free her. Richard picked her up. She was câlin, then balked, and scratched his hand. Natural for a cat caged and surrounded by chaos, we figured.

We glanced at each other. Yes?

Yes.

Signed the ream of French paperwork, showed our identity cards, paid 90 euros, got a certificate that she’d been sterilized and received all her shots.

We stood on the curb and tried to flag a taxi. None stopped, though many were free. A French couple on a nearby bench railed about the rude cab drivers in Paris.

One finally stopped, but seeing the cat in our carrier, said, Not in the car, in the trunk.

No, we said, we can’t do that to this cat, we just rescued her from prison at la Bastille.

He relented and as we headed home, told us he adored cats, but was allergic to them, was so sad to have no cat in his life. But if you’d told us that, we’d have understood, we said.

At a stoplight, he turned around in his seat to get a closer look at Jade. Oh la la, qu’elle est belle! he exclaimed.

At home, we put out food, water, and lined with a trash bag a temporary litter tray cut from a cardboard box. We’d walk the next day to get another litter box at the department store near city hall, having thrown Marley’s away.

We sat at our oak table and watched Jade pad along the edges of the living room, and then every room in the apartment, sniffing, investigating. And then she settled on the couch, looking regal and quite content. We’ll let her come to us, we decided. Let her determine when she wants contact.

That night, I stretched out on the couch to read All the Light We Cannot See. She approached me gingerly, hopped up and walked across the blanket from my feet to my hand. She butted up against it, looking for affection. I stroked her head, and she ronronnait. (You know what that means.) Then suddenly, no warning from ears or tail or viper mouth, she bit and scratched my hand, hard. It hurt.

It was probably a sign she’d been traumatized with all those dogs and other cats and humans, and being in a cage, and so we’d be patient.

Later that evening, she approached Richard in his office and bowed her head to be petted. Then turned on him and slashed his hand, with no warning.

We went to sleep uneasy. Something felt wrong about this creature. She did not speak, only squeaked as if she’d never been to meowing school.

The next day, the scratches and bites were worse. For both of us. We were now on guard when Jade approached. It was the same pattern; ask for affection, then attack without warning.

That night she bit me so hard that she raised a lemon-sized bump on my right hand that began to turn half-purple. Now I was feeling more than uneasy. I was beginning to be afraid of her. She did the same thing with Richard, biting his finger and drawing a drop of blood.

The next morning, she awakened us with a crash. She’d knocked a sculpture my sister, Jane, made of a bumble-bee bird from the mantel to the floor. Its wing was damaged at the tip.

I had a feeling that morning that I’ve never had about a cat: hatred. Her eyes were not golden, they were urine-yellow like a goat’s. She didn’t cover her shit, had never learned to do so. Was clearly a wild cat. My hand hurt, and I was worried about infection. I said to myself, I cannot live with this cat. I will never love this cat. But I’m married to a man who lived in and out of foster homes from the age of 12 to 14. To bring a cat back to the SPA, how traumatic for the cat. Unthinkable.

I had appointments that day, including a visit to my doctor. She examined my hand and said, I’m sure it’s okay, just bruising. But returning home, I felt a deepening dread of this demon cat and the decision we had to make.

Later that night Jade raked Richard’s hand so badly the wound looked like a red zipper. He called it his Heidelberg dueling scar.

With leaden hearts, we made the decision to return her to the pound. Richard made the call. After 13 weeks of study at the Sorbonne, he was able to navigate a phone conversation in French, describe the adoption, the cat behavior, find out where we could take her back that required no car.

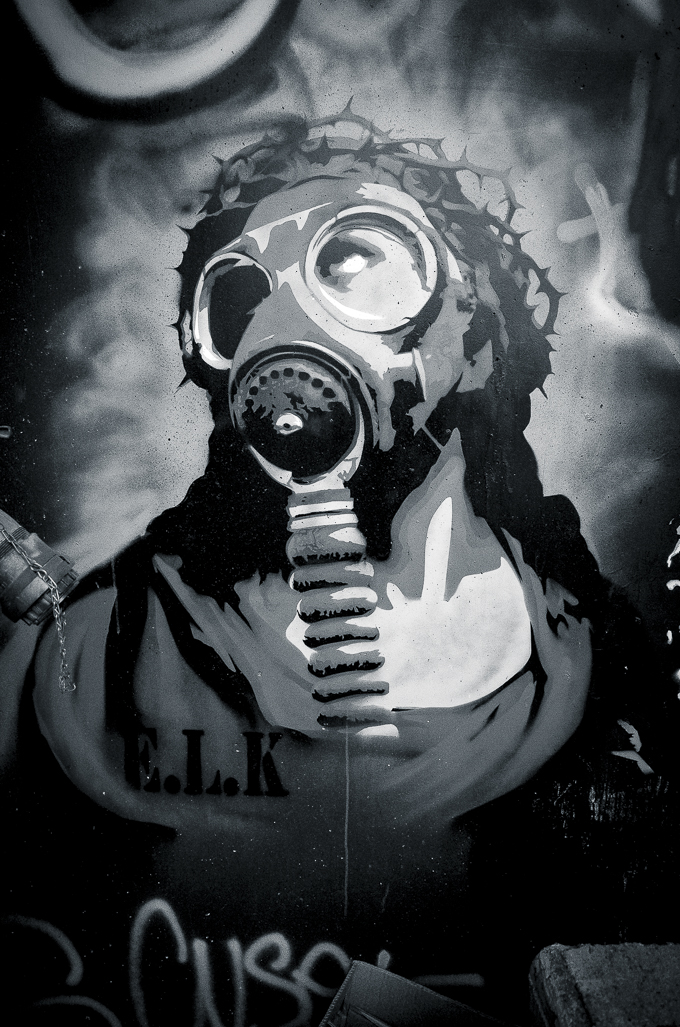

Street art © 2013 by JAZ

Street art © 2013 by JAZ

And that is how my birthday began: we rounded her up, cornered in the kitchen, hissing (she knew!), lifted her wrapped in a towel to immobilize her razor-sharp claws, got her into Marley’s old carrier, and boarded the RER train for an hour ride to the nearest shelter at suburban Gennevilliers.

The first French woman we spoke to at the shelter was skeptical and thuggish. No, they could not take the cat there because she didn’t come from this pound. Richard explained that the central SPA office, hearing that we didn’t have a car to drive to the cat’s shelter of origin several hours outside of Paris, had given us permission to bring the cat here.

She shook her head in that French fashion that says, I will find a way to obstruct this, that is why I exist.

The second, third, and fourth employees were sympathetic. Oui, they said, they would take her, though it wasn’t the center from which she came.

In our interview, we learned some French as it applies to cats. Câlin, we knew. Pavillon ou appartement? We’d thought it was a rather snobbish way of saying, Certain cats must have estates in Paris, with grounds.

Mais non. Pavillon means: This cat is so wild, so unsuited for living with not just dogs, other cats, and children, but even adults who worship cats. She can only be adopted by humans who have their own private jungle where jaguars can roam.

Street Art © 2014 by Toc Toc

Street Art © 2014 by Toc Toc

Elle n’est pas une écaille de tortue, this is not a tortoise shell, said one young woman, Morgan, named after the sorceress in the medieval King Arthur’s tales. It’s a tricolore. They are always female, and they’re known for having caractère.

Caractère translates in French to bitch. (Our cat-whisperer friend, Lisa Fimiani, told us, “Male cats are supposedly more friendly—females can be bitches, however it all comes down to the cat's personality and their interaction with you.”)

Égratigner means to shred the skin of a human.

Mordu means bitten to the bone.

They looked at our hands and nodded gravely. This cat cannot live indoors.

No, we said, she’s the demon cat from hell.

(We didn’t really say that. We know that cats understand everything you say.) We walked away feeling years lighter, and said it to each other.

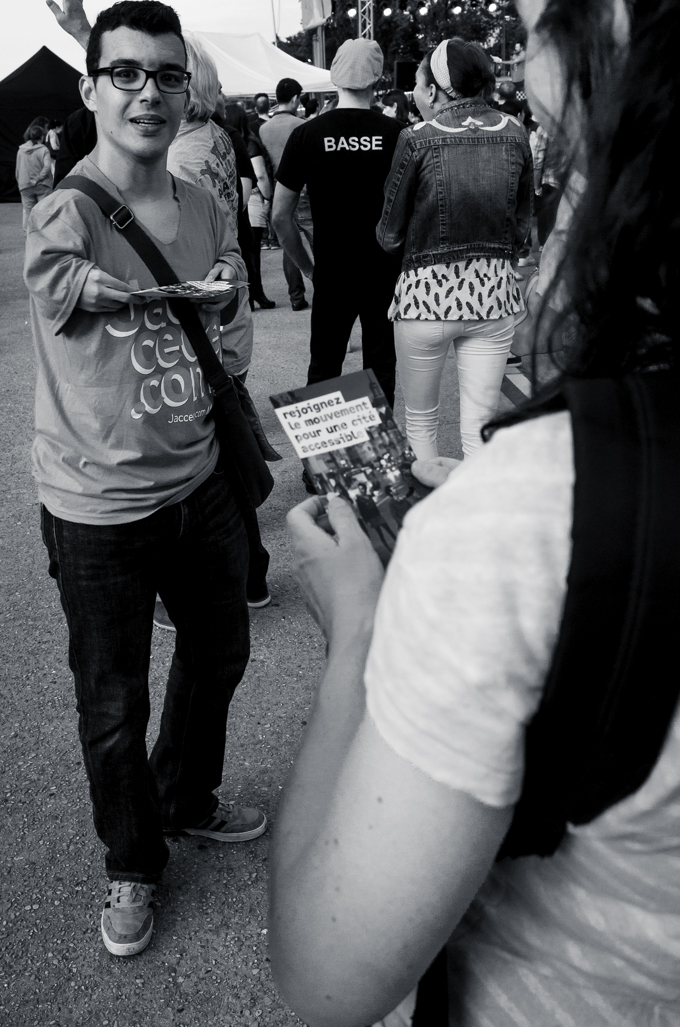

Street art © 2015 by M. Chat

Street art © 2015 by M. Chat

* Footnote: A line attributed to American author/critic/poet and wit Dorothy Parker, who is reported to have exclaimed, "What fresh hell is this?" when her train of thought was interrupted by a telephone. She then started using it in place of "hello" when answering the phone or a knock at her door.

08.15.2015

08.15.2015

Castor & Pollux,

Castor & Pollux,  Greek myth,

Greek myth,  Marley,

Marley,  cats,

cats,  family in

family in  Paris Life

Paris Life

Street art © 2013 by JAZ

Street art © 2013 by JAZ

Street Art © 2014 by Toc Toc

Street Art © 2014 by Toc Toc

Street art © 2015 by M. Chat

Street art © 2015 by M. Chat