Femininity and Feminism

04.7.2012

04.7.2012

What was it Simone de Beauvoir said about being a woman? “One is not born a woman, but rather becomes, a woman.”

I disagree. Nothing could be easier for most of us than being the sex we are born.

While men's and women's differences are to some extent culturally determined, many of our differences are innate.

Women are more attuned to nuances of relationship than men.

Women are more radial in their sensibility.

Men tend to find it easier to stay focused on getting to their goals.

Men tend to be more linear in sensibility.

Generalizations, I know. But for the most part, I’ve found them to be true.

I know a gifted psychotherapist, one of whose specialties is couples counseling. She once told me that with most couples, when you ask the man what he wants in a relationship, she usually hears, “I just want her to be happy.”

In the realm of relationships, men are simpler, she says. They want to be appreciated. They want to be admired. They want their women to be happy.

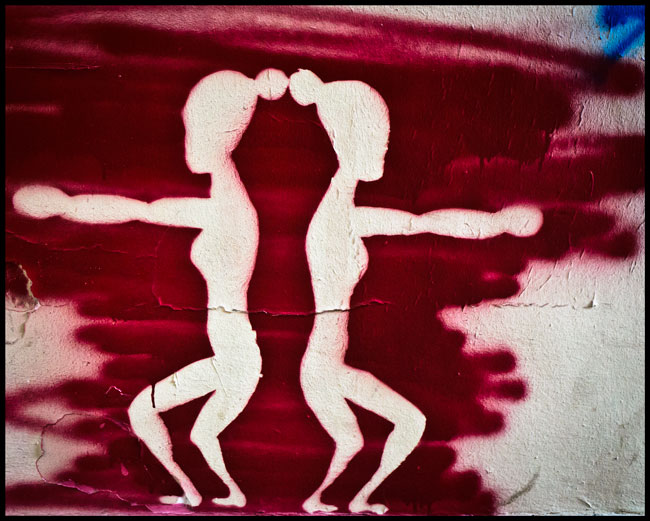

The great psychiatrist and mythographer, C. G. Jung, had another angle on the subject: he came up with the notion of the anima and the animus, the contra-sexual being inside both women and men. Men have within them an image of the feminine, or a female soul. Women have within them, the image of the masculine, or male spirit.

I went on amateurishly to sketch a plan of the soul so that in each of us two powers preside, one male, one female; and in the man’s brain the man predominates over the woman, and in the woman’s brain the woman predominates over the man. The normal and comfortable state of being is that when the two live in harmony together, spiritually co-operating.

To be successful the mind must possess an ignorance of sex, Woolf writes in A Room of One’s Own:

the mind of an artist, in order to achieve the prodigious effort of freeing whole and entire the work that is in him, must be incandescent, like Shakespeare’s mind.

I seem to be circling around what I want to say. And I can’t really approach it through generalizations. (If I were a man, I’d have gotten to the point by now.) I can only approach it by recalling certain moments in my life that still resonate.

Some happened before I was born. Others happened afterwards.

What shall I call these moments?

What if they all together added up to a constellation, a metaphorical shape in the sky? A shape I won’t recognize without first laying them all out, like stars?

So, stars:

Star: It is 1945. My father is in the Navy. My mother travels from their apartment in Greenwich Village to her childhood home in Fairmont, Minnesota.

Her father, my grandfather, had left the farm on which he was raised to go to medical school, to escape the life of a farmer. He was now a brilliant medical diagnostician, a beloved family doctor.

His oldest child and only daughter, my mother, always wanted to be a doctor, and had her father’s gift for it.

No, he said, since they wanted six children, he’d be happy to earn the living for the family while she raised the children.

My grandfather and my mother’s brother, himself a doctor, also dissuade my mother from going to medical school. Why do women need to go through all that?

Star: My parents have five children rather than the six they planned. Four are girls. My brother is given a middle name. We girls are not, presumably because we’ll marry and get name #3 that way.

I do so, with no discussion of his decision. We move from a ranch in Novato to an 85-foot schooner. We move from land to the sea. We move from the life of being a couple to being a “crew.” I don’t question that he hasn’t even asked me whether this life appeals to me.

Star: We sail from Honolulu to Marina del Rey. We are a crew of ten. We move to a shipyard in Newport Beach, where we’ll renovate the ship for the next two years. Everyone chooses jobs on the schooner. Since I’m the only woman who lives full-time on the boat, it is assumed that my job is to cook. I don’t like to cook, though I’m perfectly good at it. And anyway, I can’t rebuild engines.

Star: It’s 1972. It’s the Virgo decade, the decade of Demeter. Everyone is tuning up their health by careful dietary choices. The men want no dairy in their diets. They want home-made corn bread and three meals with three or four courses each a day. But we’re rebuilding the galley, and don’t have a refrigerator or stove, so I must market once or twice a day and cook on an hibachi in the noisy, dusty shipyard.

At the market one day, I pick up the first issue of Ms. Magazine.

The ship is an optical illusion, a mirage. From the outside it looks like the ultimately glamorous life: we’re rebuilding her to sail around the world.

Groupies flock around the single male crew members. These are seriously mentally challenged “chicks” and the turnover is high. It is my job to comfort the broken hearts of girls who were attracted to adventurous guys who have something they want (a free ticket to sail around the world) but who quickly grow tired of them.

From the inside, this life is anything but glamorous. It is hard physical labor all day long, seven days a week. It is a perfect life for an extraverted action type who loves being surrounded by people and adores physical labor, like sanding masts, rebuilding engines, pumping the bilge.

For an introverted intuitive type like me (you know, a dreamer), it is my definition of hell.

I beg my boyfriend to leave the boat. He doesn’t hear me for two years. “Think of the adventures we’ll have sailing around the world,” he says.

But it’s too many people, too little time for reading and writing or any of the things I like to do.

Star: A. and I rent a little apartment on the beach in Laguna Beach. It is so small that we have to halve the day. He leaves in the a.m. to give me silence to write. I leave in the afternoon to give him solitude to paint. His friends knock on the door all morning looking for him. I ask him to tell them to stop by during his “studio hours.” One leaves me an anonymous nasty cartoon. How dare a woman try to have silence, a space of her own?

I ask A. to go to counseling with me. He doesn’t see the need, refuses.

I leave him, get involved with another man.

Now A. offers me whatever I want, silence in the morning, communication, counseling, anything. But it’s too late.

Star: I live in hiding on the other side of the country for a year and a half, until he tracks me down by breaking into my parents’ home.

Star: Ten years later in Santa Fe, I become a traveling art dealer. I don’t pay enough attention to appearance, clothes, but in this job, with high-end buyers, I must refine my wardrobe and appearance. I borrow a gorgeous black cotton dress from a good friend, pair it with a concho belt my mother has given me, and looking my best, interview for the job, get it, and go to artists’ studios to look at their work.

One of the male painters says, “She’s too good-looking to be any good as an art agent” to a friend of mine, who tells me what he said.

In my first art-selling trip to Arizona, I snag three banks, am asked to fill them with art of my choosing, paintings and sculptures of the artists whose work I carry. I place no paintings by this artist in any of the banks. Another artist is able to put a down payment on his first home from the paintings that have sold.

Star: In Santa Fe I complete a vision quest of thirty years. What I discover at the center of the labyrinth is that the breakdown I experienced in my first year of college, post-loss of religious faith, post-boarding school structure, was not a merely personal drama.

The confusion about values, about my path and focus, was a refusal of an entire cultural construct: a patriarchal world in which nature is not honored, women are not revered, all is driven by the masculine values of progress, economics, power, domination. And the soul, being, relationships, love, the sacred, the earth, are lesser values or ignored altogether.

Long after I become clear about my own spiritual values, and work…

Long after the influence of Virginia Woolf, Simone de Beauvoir, Betty Friedan, Doris Lessing, Anais Nin, Ms. Magazine…

Long after the lessons of the ‘60s and ‘70s about equality between women and men have become a part of our cultural conversation…

I hear women denying they are feminists, or splitting hairs in defining it:

“Poor men—it hurts their feelings.”

“Feminism needs to be more feminine.”

Or from women who’ve been getting by for years by being seductive: “I’ve never had any trouble as a woman getting what I want.”

“Poor white people. You wouldn’t want to hurt their feelings, now would you?”

“We just need to be more pliable, less demanding.”

This is just plain absurd. Nothing at all changes without the first revolutionary activists. It’s their very anger—that fire, that light—that blazes the trail, lights the way.

I have a few questions I’d like to ask you women who deny or negate feminism:

Have you ever been dissuaded from doing the work you wanted to do because you’re a woman?

Even if you proceeded with the work you wanted to do, have you ever had others in your life consider it secondary to matters of relationship, others’ expectations of you as wife, girlfriend, mother, friend?

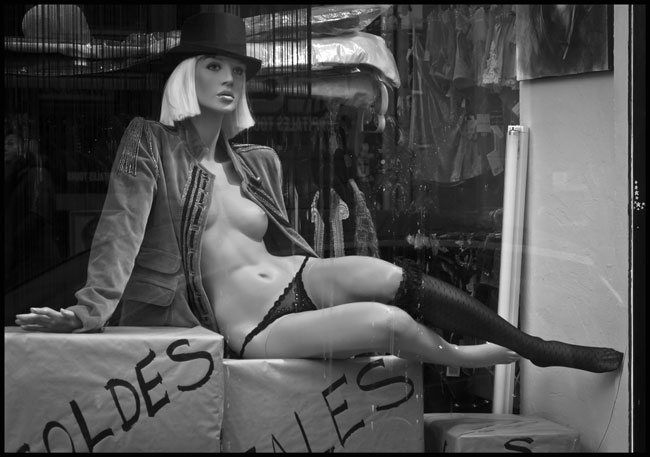

Have you ever been punished for your looks—looking “too good,” or looking “not good enough?”

Have you ever had life decisions made for you, without being consulted, because you are a woman?

Have you ever feared for your life because a man wanted something from you that you didn’t want to give him?

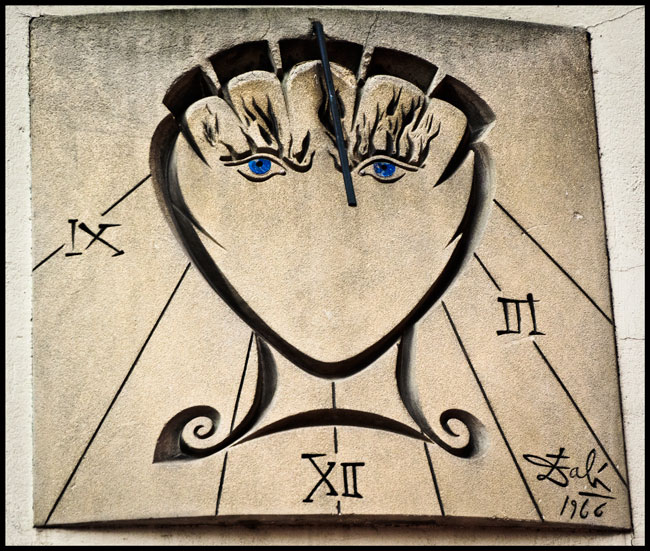

Street art by Salvador Dali

Street art by Salvador Dali