The Convocation of Animals

09.11.2013

09.11.2013

Photo courtesy of Suki Edwards

Photo courtesy of Suki Edwards

Some of us gathered at a computer, adding names to the guest list for Jane’s memorial celebration.

Some of us had just finished writing her obituary.

One of us had arranged on her bed an embroidered gold, red and white kimono with a medicine necklace, both gifts sent to Jane.

Some of us felt her death as so strange that our cells would be rearranged.

Some of us went to a dumb film and drank too much one night.

Some nights some of us dreamed of Jane.

Some nights some of us couldn’t sleep.

One of us made long lists of things to do.

One of us saw images of Jane’s sculptures in cloud shapes.

One of us had a massage and the masseuse touched her back above her heart and released the rain.

Some of us went to the market and bought Gerber daisies and sunflowers to honor her innocent spirit.

Some of us went shopping for candles, and found white lotus blossoms that lit up the moment they touched water.

One of us passed an empty frame in the store, and was seized by the knowledge that she was gone.

Some of us were soothed by calls and messages from family and friends.

Some of us talked one night about how impossible it seemed to write a eulogy, our feelings for her too large to fit into three minutes.

One night one of us said, All I want to do is stand up and howl.

Photo courtesy of Hank Kitchell

Photo courtesy of Hank Kitchell

One of us said, we could make different animal sounds, and began to hee-haw like a donkey.

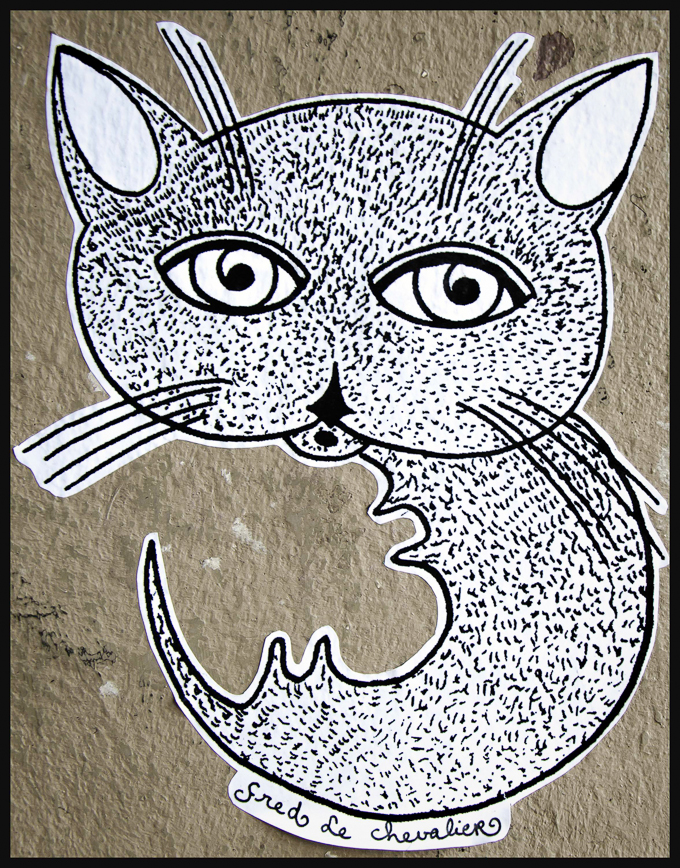

One of us said, we could find animal masks and perform a chorus of animals to honor her, since many of her sculptures were of animals.

One of us laughed and said, But wouldn’t it seem too weird?

Some of us went to look for masks, but couldn’t find Owl, Fox, Bear, Cat, Monkey, Donkey.

One evening the ceremony was held at the farm of friends, a sweep of lawn sloping down to a lake fringed by tall pines.

Some of us who owned the farm lost a brother days before Jane’s memorial, but still wanted to host the event.

Some of us came early to set up tables under open tents like sails.

Some of us created a slide show of Jane’s life that was shown on a giant screen.

Some of us gathered songs she loved, and one of us played them throughout the evening.

Some of us opened boxes of candles and placed them on a table at the edge of the lake.

Some of us fanned open paper flowers for the tables.

One of us gave food from his own bakery.

Some of us, the first guests to arrive, were followed down the hill by a hawk.

Some of us had travelled many miles across the ocean.

One of us bicycled there from Victoria, British Columbia.

Some of us had known her since childhood.

Some of us had been her husbands, including her first and last.

Some of us had been caring for her for years.

One of us had moved to Seattle from New Zealand to be by her side the last months of her life.

Some of us saw sea gulls and thought of Jane.

Some of us saw whales.

One of us saw a sparrow hawk flying with another hawk through the desert.

One of us saw a turquoise dragonfly dart across the lake.

Some of us gave eulogies and some of us wept.

One of us heard a wise woman say that in certain African funeral services, hecklers in the back of the room balance the gravitas with irreverence.

Photo courtesy of Hank Kitchell

Photo courtesy of Hank Kitchell

Some of us, after the eulogies, put on masks—of Horse, Squirrel, Cardinal, Rat, Pigeon, Chicken, Unicorn and Duck—and danced and called out to Jane through the voices of the animals.

Some of us sat with old friends telling stories of Jane all night.

Some of us gathered around the campfire at lake’s edge listening to stories about animal visitations after death.

Photo courtesy Suki Edwards

Photo courtesy Suki Edwards

Some of us wrote messages to Jane on the candles, and floated them on the lake after dark, like fireflies under a three-quarters full moon.

One of us wrote, “I’m still in love with you, Jane.”

One of us heard the Rodriguez song, “I think of you,” and wept in the darkness.

One of us had cold ankles as the night grew deeper, and a white dog named Lily came and sat backwards so that her hind fur warmed those ankles.

Some of us human creatures felt the grief lift because we had joined together to celebrate our love for Jane.

Photo courtesy Hank Kitchell

Photo courtesy Hank Kitchell