Date night! The plan: we’ll walk a half-hour to the Art Jingle gallery in the Marais where Jérôme Mesnager’s show is opening. Richard suggests a dinner afterwards at a favorite Mexican restaurant just half a block away, “even though it’s not Sunday night.”

It happens so often now that it no longer surprises me. I’ll be thinking of something and without a word exchanged, he’s on the same wavelength.

I’d been musing on the odd resonance between France and Arizona. So many friends and acquaintances who grew up in Arizona have ended up living in Paris or southern France, or visit as often as twice a year. Mort, Edith and Don, Amy, Audrey and I and others. Yet Arizona and France seem to have so little in common.

Growing up in Arizona, my family went out for Mexican food every Sunday night. It was a sacrament. Mexican food is childhood in the Sonoran desert to me.

We squeeze into the elevator, Richard sideways with all his camera equipment in a pack on his back.

“You look like a camel,” I say.

He makes a noise exactly like a camel, a talent I wasn’t aware he had. All the way down to the ground floor, he groan-bleats like a camel. I’m laughing imagining our gardien rushing to the elevator door in alarm.

We set out at 5 in a steady rain, laughing at the unlikelihood that we’d be walking half an hour anywhere in the rain if we still lived in L.A. Our only concession to the weather is the choice of a less scenic route across the Pont de Sully and up Blvd. Henri IV to rue de Turenne—it’s faster.

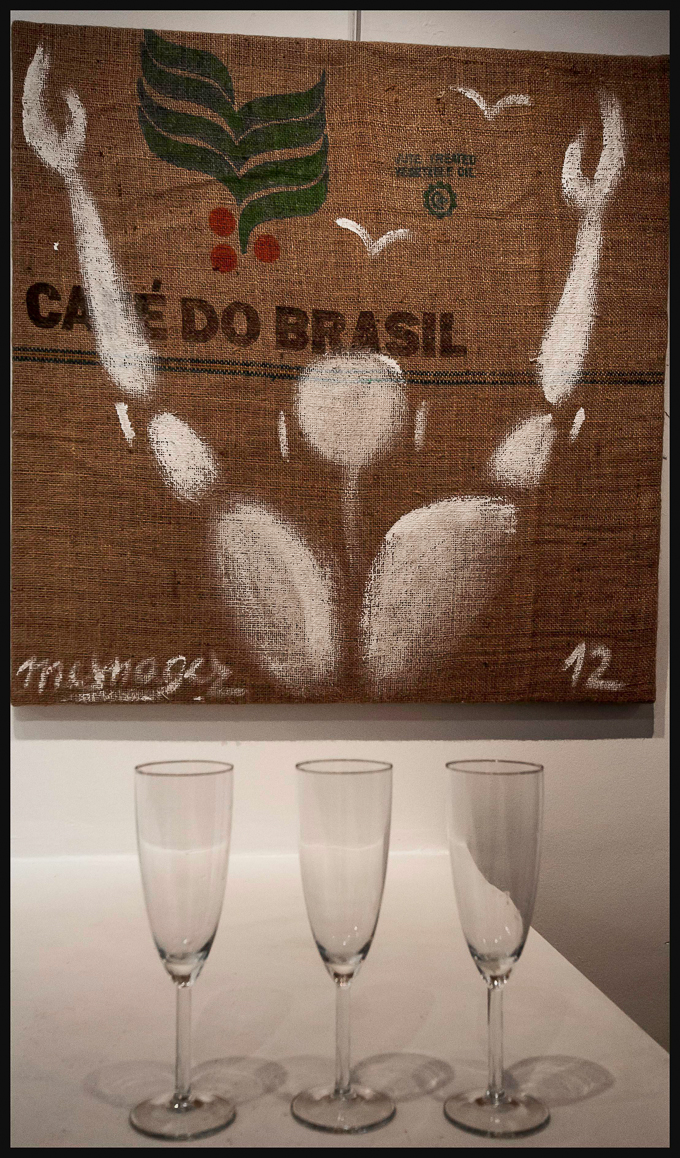

We are the first to arrive, Richard’s preference so that he can photograph the artwork “without a bunch of people standing in the way.”

A young woman in blonde braids shows me around the gallery, describing each painting, including its colors. As a former art dealer, I’m tickled by this approach. A blue background, you say?

In comes a Frenchman who circles the gallery, then asks me which painting is my favorite.

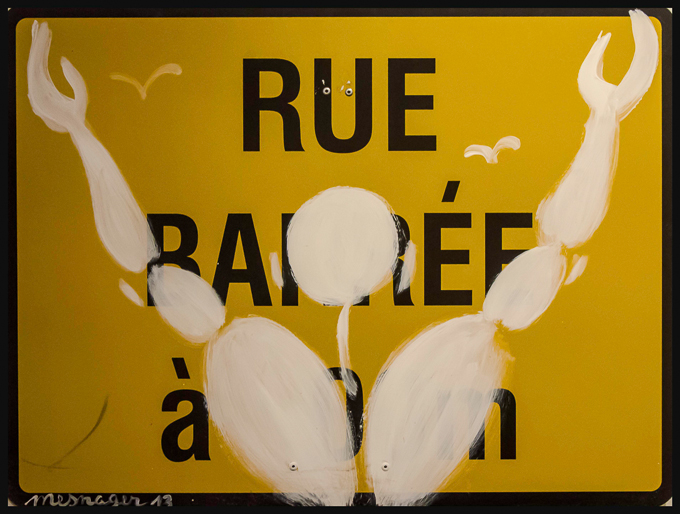

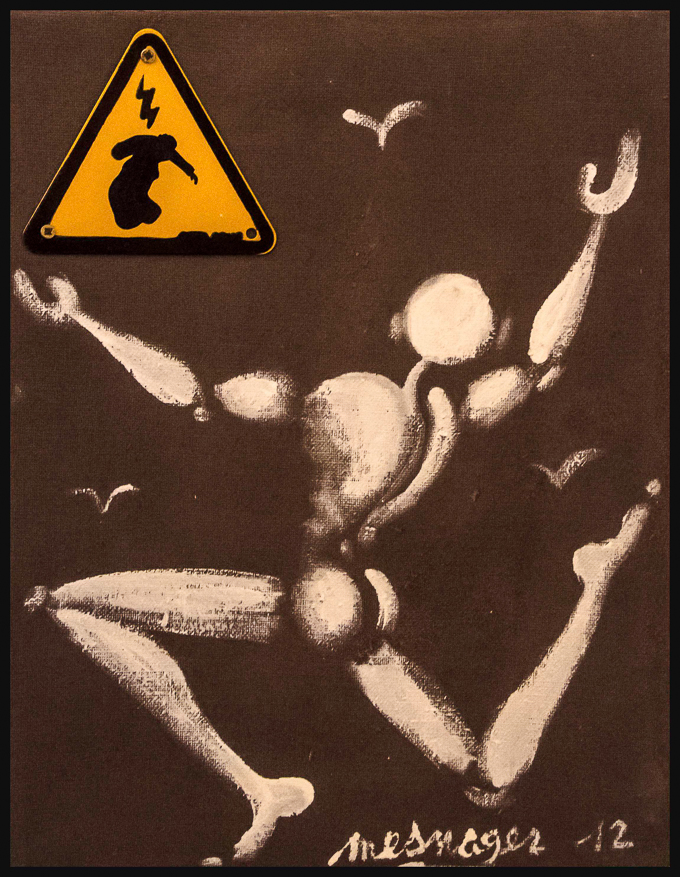

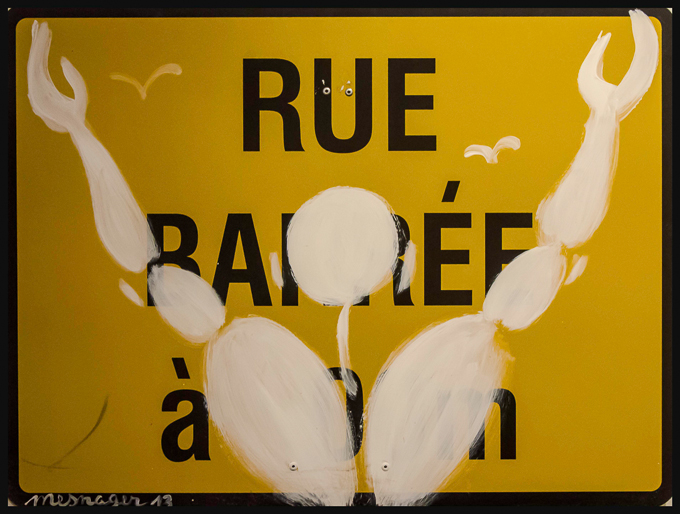

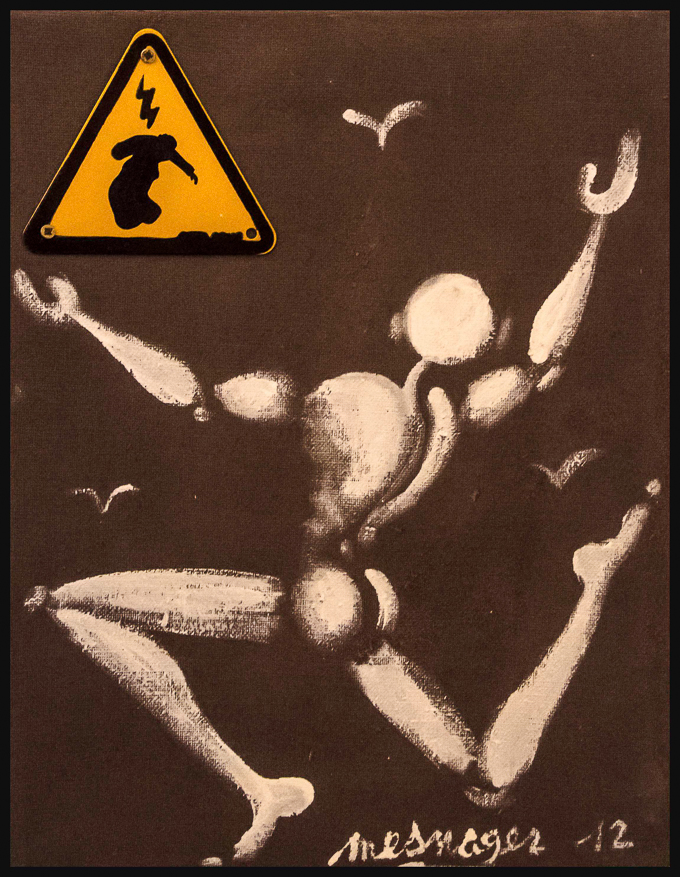

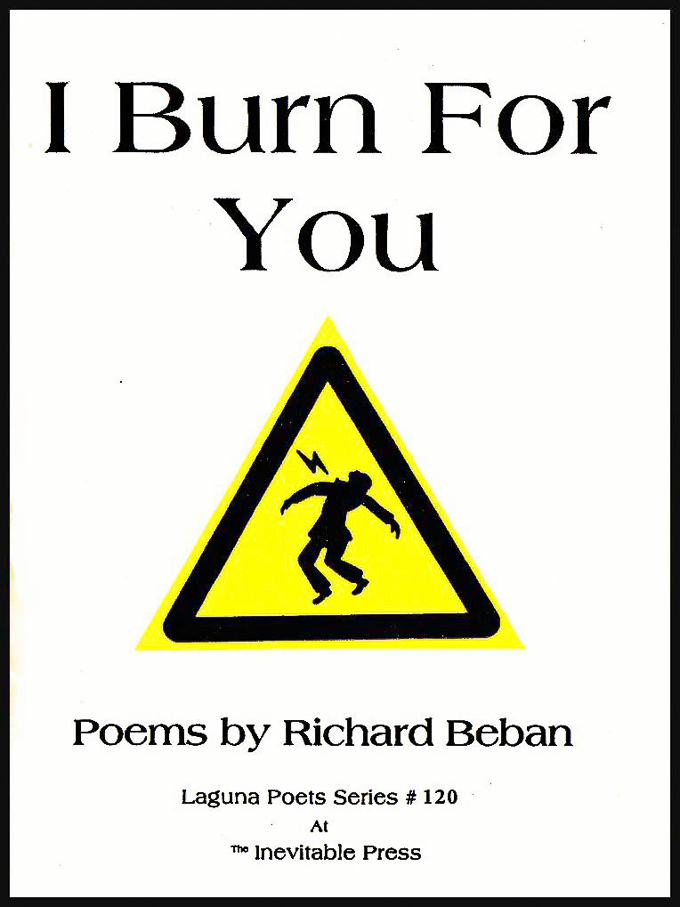

“Coup de foudre,” I say. We examine a brown canvas on which Mesnager has painted one of his corps blanc, reacting in awe to a small yellow plaque that bears the image of a man struck by lightning--a sign warning of high voltage, which we see often on Paris electrical switching boxes.

Richard had chosen that image in 1999 as the cover of his second chapbook, a book of love poems, written after we’d both been hit by the coup de foudre of love.

“Buy it!” says the Frenchman.

I’d already checked the price. “We only buy paintings before the artist is famous,” I say.

He corrects my French: “Célèbre,” he says.

“Ah, oui, merci.”

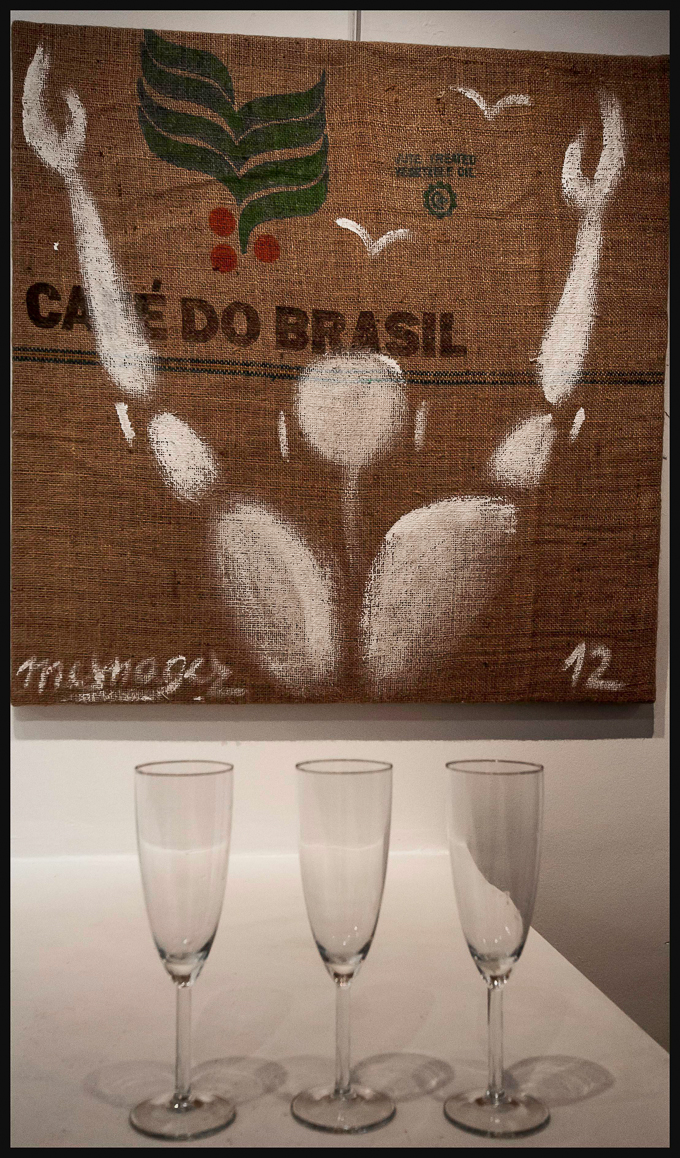

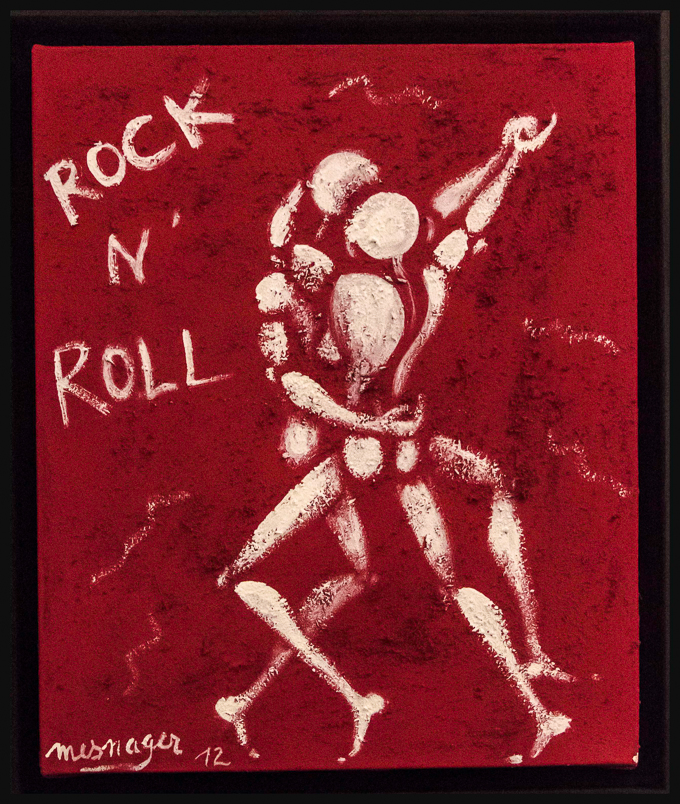

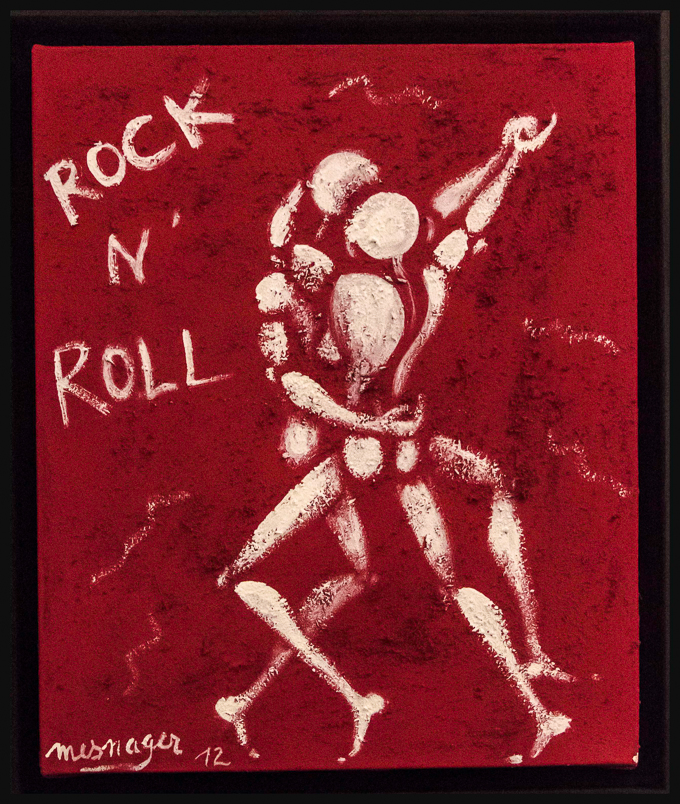

Other people float into the gallery. Everyone seems to be in the lightest of spirits, as if they’ve inhaled the joy of Mesnager’s buoyant dancing figures.

The artist blows in, an ebullient elfin face, faded red jeans, champagne spirit.

Seated at a round table in the corner, on which are a few books of the fifty-two-year-old artist’s work, including his autobiography, I survey the paintings and the people. He takes a seat, and one by one, I watch the gallery-goers come up to him to pay their respects.

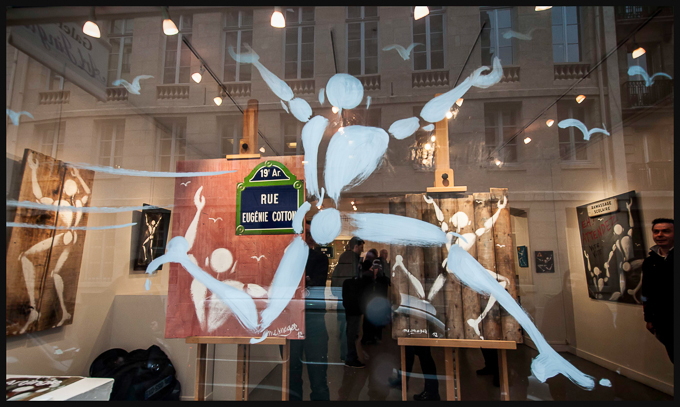

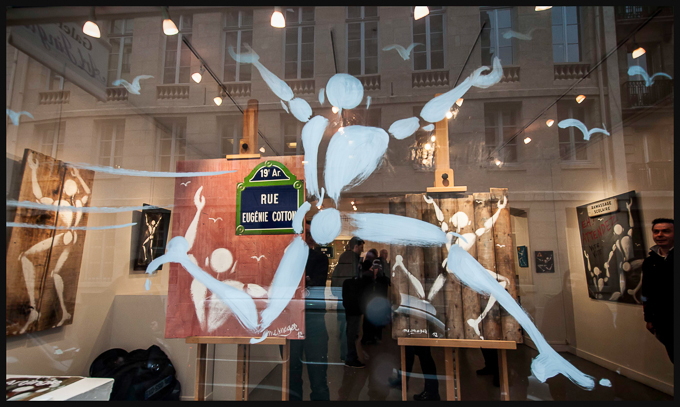

Jérôme Mesnager (the "s" is silent) is one of the original modern Paris street artists. He began in 1980, and created his first painted white figure in January 1983 as “a symbol of light, power, and peace.” They have since leapt continents, his work can now be seen on walls around the world. There is even an image of his Corps Blanc climbing up the Great Wall of China. Stories tumble from him, he is entertaining his fans. Men unfurl works of his on paper they’ve had for years, and ask him to sign.

Richard, wearing black, is dancing around the room, a corps noir, capturing every image and face.

An odd sort of date, huh? For us, though, these luminous figures perfectly capture our own joy at arriving in Paris two years and two months ago. We found this image on a wall on rue Mouffetard, long before we knew Mesnager or his seminal role in Paris street art, which Richard photographed for our second Paris Play post, “The Bell of Light."

And we’ve used his work in other posts, here, here and here, for example.

The champagne is flowing, the gallery buzzing. Jérôme selects a brush from a can, dips it into a pot of white paint, and approaches the inside gallery window. He lifts his arm and with sure strokes—les bras, les mains, les fesses, les cuisses, pieds, tête, oiseau—transforms ebullient spirits into ecstatic image. People crowd the sidewalk, snapping photos from the outside. I stand behind the easels and watch.

Richard brings me a glass of champagne, and introduces me to Véronique. She is Jérôme’s older sister, and a more protective, loving sister you cannot imagine. In his autobiography, he writes that she was the first appreciator of his art, and that he gave her his very first creation. It’s impossible to go to an important opening by any Paris street artist now, not just her brother’s, and not run into Véronique Mesnager, blessing other artists and supporting the growing community.

Véronique and her brother Jérôme

Véronique and her brother Jérôme

Richard has his photographs. We glance at each other: we’re starving! The restaurant is open, and it’s authentic Mexican food, the way it’s made in Mexico City.

We communicate with the waiter in a ridiculous mix of French and English and un poco de español.

The guacamole is one of the only two we’ve found in Paris that tastes like real guacamole, the chips so fresh they’re fragrant. We sit on a banquette next to the bar, and talk about the dark and the light in our lives and the joy that runs through all of it. The waiter, hair in a pigtail, brings chicken flautas for me, chorizo and potato tacos for Richard, and black beans.

At the same event, Richard has seen the faces, and I’ve heard the stories. We swap impressions. Richard is struck by the fact that Jérôme has such a charming, joyous, elfin face, yet that he is most famous for characters that have no face at all.

And, the waiter interrupts, would we like dessert?

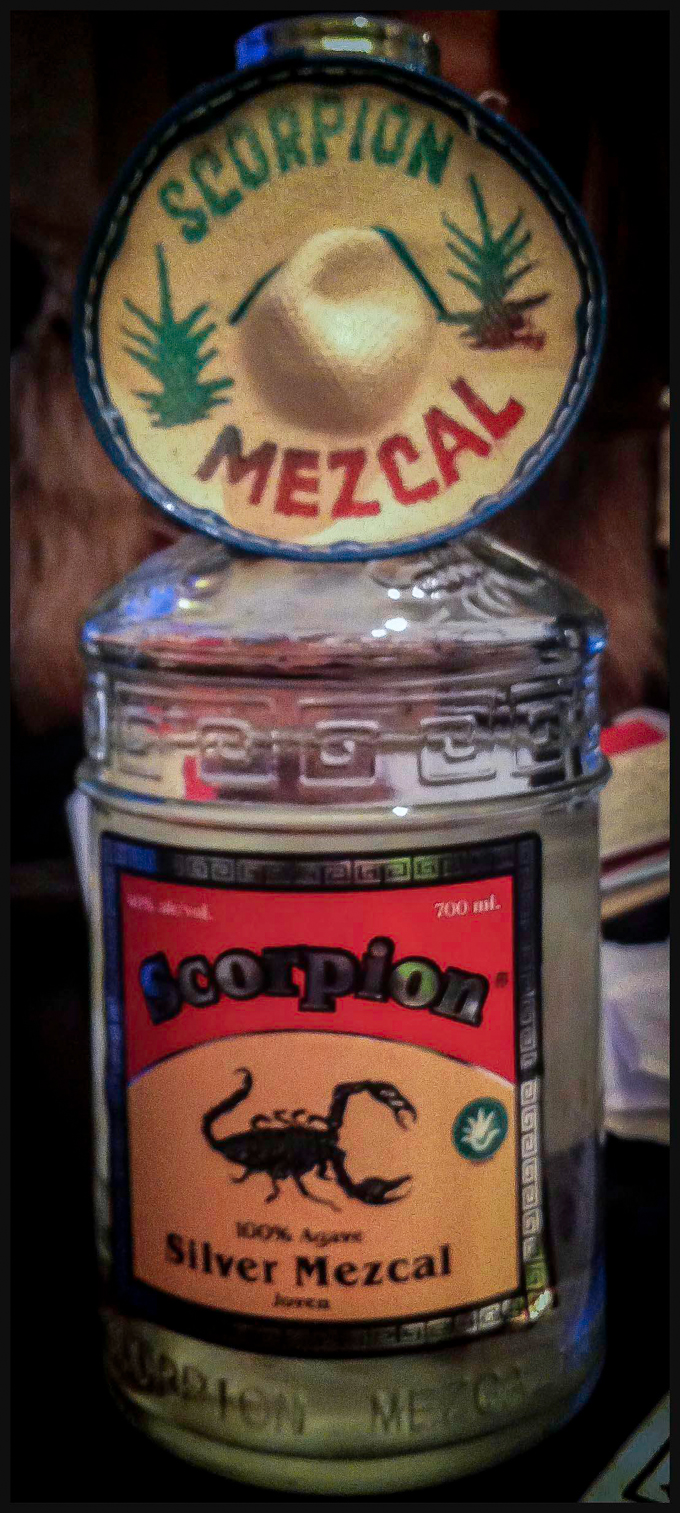

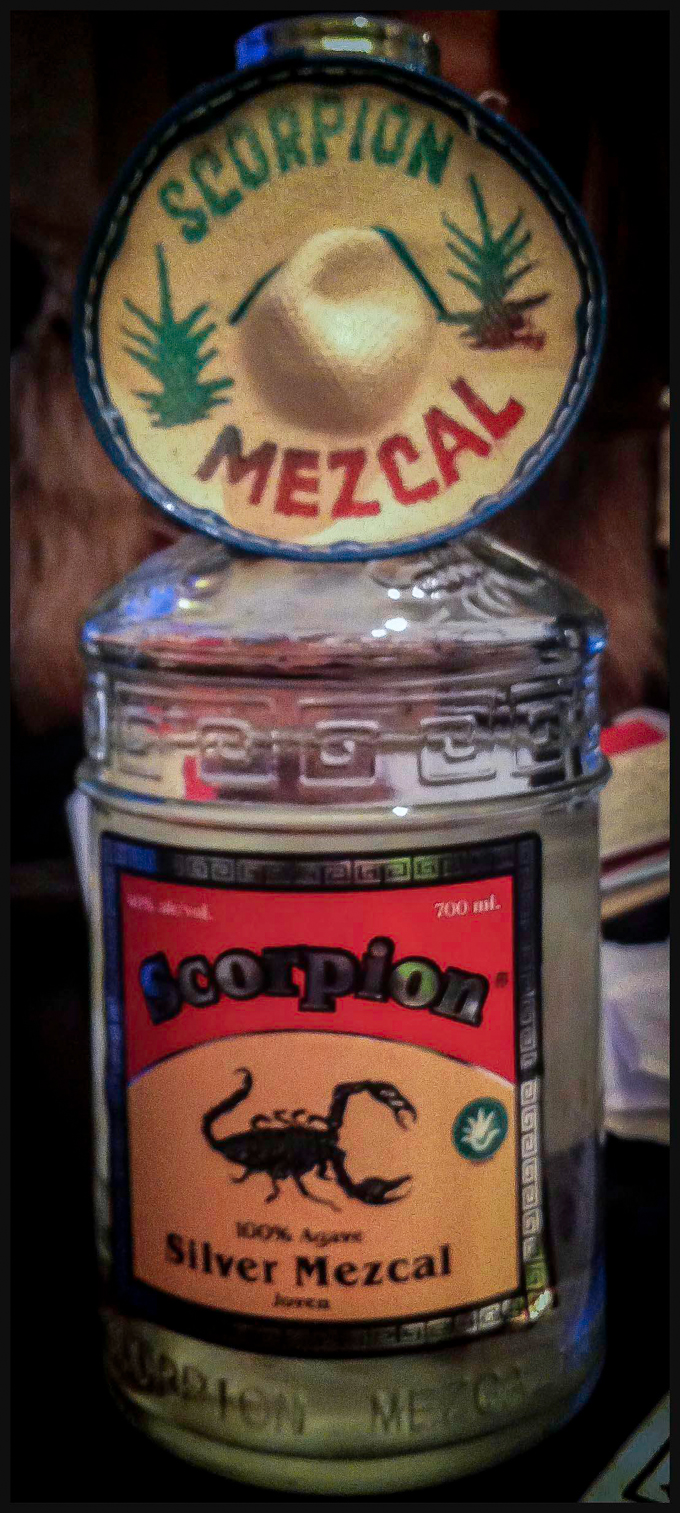

No, but how about a shot of that Scorpion Mescal above the bar?

The waiter, grinning, takes the bottle down, and places it on our table.

“What happens if you eat the scorpion?” I ask. “Isn’t it poisonous?”

“It won’t kill you,” he says. “It’s strange. France won’t allow in tequila with worms in it, but scorpions? No problem.”

“Who orders it, mostly Americans and Mexicans?”

“No, it’s the French who keep coming back and ordering shots, hoping to get the scorpion.”

The level of liquid is low, within inches of the scorpion. Shall we have a shot or two in honor of the Sonoran desert, right here in Paris?

Later at home, wondering if mescal is another name for tequila, I look it up and find: Mezcal is made from the maguey plant, a form of agave plant native to Mexico, whereas tequila is made from the blue agave. The saying in Oaxaca is: “para todo mal, mezcal, y para todo bien también” (“for everything bad, mescal, and for everything good, as well”).

But this is what slays me: “The maguey was one of the most sacred plants in pre-Hispanic Mexico, and had a privileged position in religious rituals, mythology and the economy. Cooking of the “piña” or heart of the maguey and fermenting its juice was practiced. The origin of this drink has a myth. It is said that a lightning bolt struck an agave plant, cooking and opening it, releasing its juice. For this reason, the liquid is called the “elixir of the gods.”"

A coup de foudre kind of night, everywhere we turn.

04.28.2013

04.28.2013