A Bell Named Marie

03.24.2013

03.24.2013

Richard was out shooting peacocks in the Bois de Boulogne, while I was home doing some spring cleaning. We are to meet in front of Shakespeare and Company to witness the first ringing of the nine new bells at Notre Dame, to celebrate the eight-hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of the cathedral.

As I turn from rue Lagrange towards the Seine, I can see thousands of people here for the event.

There he is! We embrace, then weave between cars and motorcycles across the Quai de Montebello. Richard finds a spot against a wall from which to record the sounds. I want to see if I can get closer, though the crowd is daunting.

I cross the Pont au Double and follow two teenage boys who part the crowd like Moses. We make our way to a low fence which holds us back from a big swath of grass. You must not walk on the grass in Paris. Pelouse au repos hivernal du 15/10 au 15/04. The grass is having its winter rest from October 10 to April 15.

A Spaniard is holding a black-eyed, black-haired child, a girl, to my left. How do I know they’re Spanish? Because the child is chattering in Spanish with a Castilian accent.

The bells begin tentatively. The first sounds are almost delicate. Bright and clear, bringing tears.

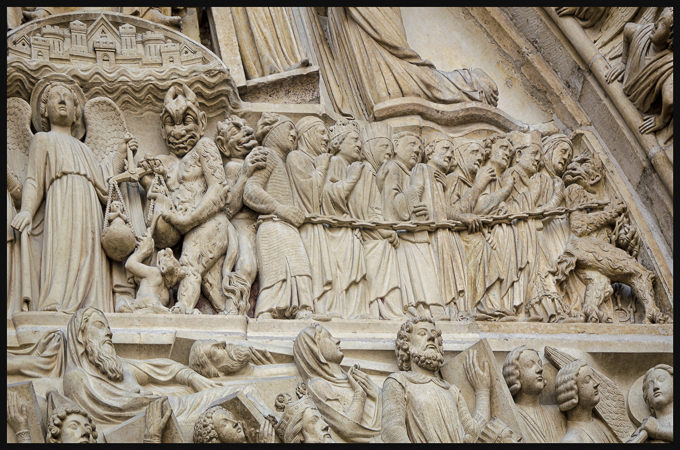

I look around me at the crowd and what this means to Catholics around the world. During the French Revolution, all the bells except one were melted down for cannons and coins. Only Emanuel, the biggest, a 13-ton bourdon bell, remained. Four other bells were added in the 1850s, but they were so discordant that Parisians joked they’d made Quasimodo deaf. But for years they rang every 15 minutes in Paris, ding dang.

I can see both the front of the cathedral and a huge screen on which Archbishop Andre Armand Vingt-Trois is speaking in slow, clear French. It is a pleasure when the rhythm of speech is slow enough for me to capture it all. That is, if the Spanish child, mouth smeared in chocolate, weren’t asking loud questions right next to my left ear. I glance at her, at her father. It’s written on his face: My child is the exception to all rules. From every courtesy such as silence in churches, films, libraries, my child is exempt.

A family of teenagers with a gray-haired woman elbows through the crowd. Everyone glares. The teenagers muscle their way to the low fence, easily vault it and onto the grass. The woman chooses not to follow. She chooses instead to squeeze in next to me between the Spanish child and my ribs. She has no sense of bodily space (which most French people decidedly do) and keeps bumping against me and the couple in front of her.

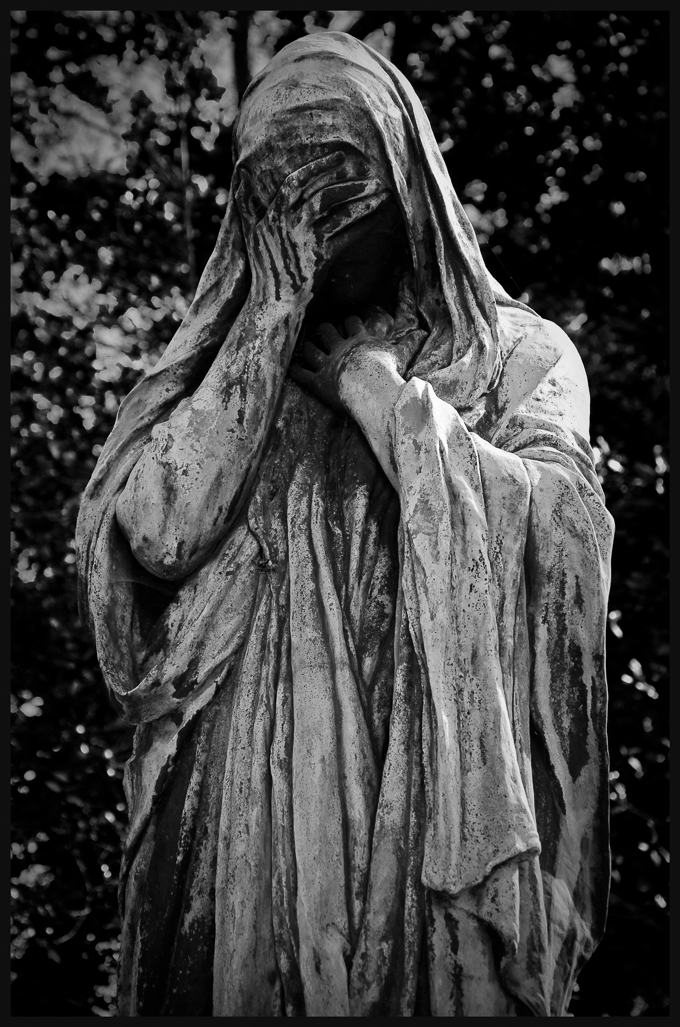

At last the bells all ring. I watch the close-up images on the screen. They remind me of something. Yes, the great iron skirt of a woman swinging, her legs rigid, her ankles and feet tied together—no, fused. An eternal virgin. The Virgin Mary. Is this bell the biggest of the new ones, Marie? She is the only new bell which will ring in the Gothic south tower, joining Emmanuel. The other bells—Jean-Marie, Maurice, Benoît-Joseph, Etienne, Marcel, Denis, Anne-Geneviève and Gabriel—will sound out in the north tower, high above the Seine.

My mind floods with images from the film I saw the night before: Vision: From the Life of Hildegard von Bingen. A German film directed by Margarethe von Trotta in 2009, it stars Barbara Sukowa as the 12th century Christian mystic, Benedictine nun, composer, philosopher, playwright, naturalist, scientist and ecological activist, Hildegard of Bingen. It is a great film, a film of beauty and suffering and gravitas. It is gripping for its dramatization of an historical character of visionary brilliance.

And it illuminates the mythical. Hildegard lived during the middle point of the Piscean era, at the beginning of the twelfth century, half way between the birth of Christ and present time, from 1198 to September 17, 1179.

Pisces, the last sign, of dreams, suffering, compassion, final reckoning. Christ, the fish, Poseidon and Pisces. And its opposite polarity, the Virgin Mary, the spiritual body, Demeter and Virgo. The suffering of the monks and nuns, the celibate marriage to the divine—it is all here in its agony and splendor. At that time in Catholic history, the price for a nun getting pregnant by a monk was banishment or often, suicide. And the price for the monk? Nothing.

And so this metaphor of a bell named Mary, Marie, the holy Virgin.

Some around me jostle and eat chocolate. Others film the ceremony on the screen. Others watch, faces uplifted, tears streaming their cheeks. People have come from all around the world to be here for this moment, the first time in over two centuries that the cathedral has had a full complement of bells.

The music ends. One of the artisans of Cornille-Havard (France’s most renowned bell foundry) who made these bells lovingly describes his craft. This is the quality we love most about the French: their exquisite attention to the details of artistic craft.

I make my way through the scattering crowd back across the Pont au Double to meet Richard at his spot along the Seine. There he is! Unfortunately, his video captured mostly the sounds of traffic and talking humans, rather than the new bells. But we were there.

(And here's a link to TV channel BFM, which had better audio than we did.)