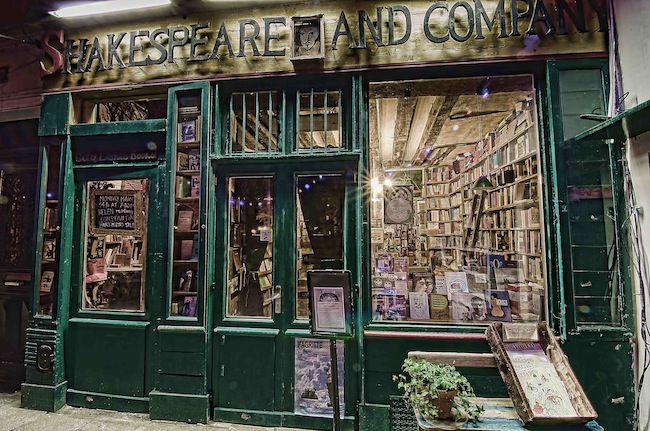

Before I Die...Paris Play #100

09.22.2012

09.22.2012

To celebrate our one-hundredth edition of Paris Play, we've created our third Surrealist Café, our virtual gathering place where readers/friends contribute, and we curate.

Last week, we asked you to fill in the blank: Before I die I want to ______________.

This week, your heartfelt, soul-deep replies; we tried to honor them each with the best illustration that we could create.

Thank you, everyone who played. You make our lives so much richer with your depth, and your willingness to participate in community. When we first arrived in Paris, we worried about isolation from our loved ones. Hah! Not a chance.

May all your dreams come true before you die.

Love,

Kaaren and Richard

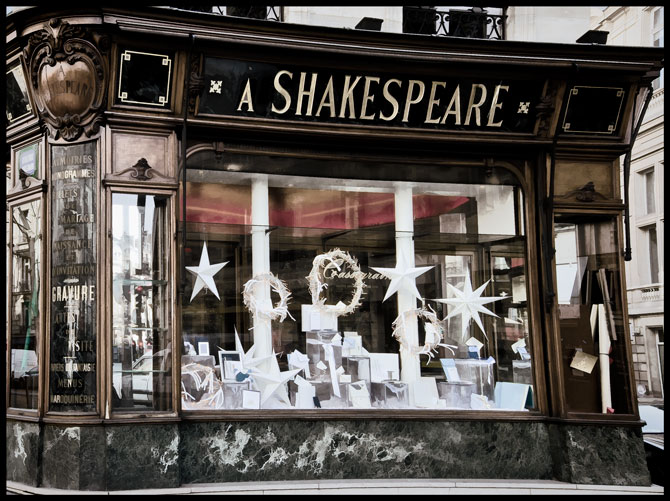

Ted Tokio Tanaka

Before I die I want to feel comfort to move on to after life.

Porter Scott

Painting by Ku Gao (c) 2012

Painting by Ku Gao (c) 2012

Before I die, I want to tie the ribbon on my life (or come full circle) by signing all of the paintings of my youth and selecting all of the best photos I’ve taken over the years; thereby leaving my small visual mark on the world as my most satisfying accomplishment!

Gayle

Before I die I want to marry someone rich to take care of me.

Anna Waterhouse

Before I die I want to see God, preferably in Italy.

Ann Denk

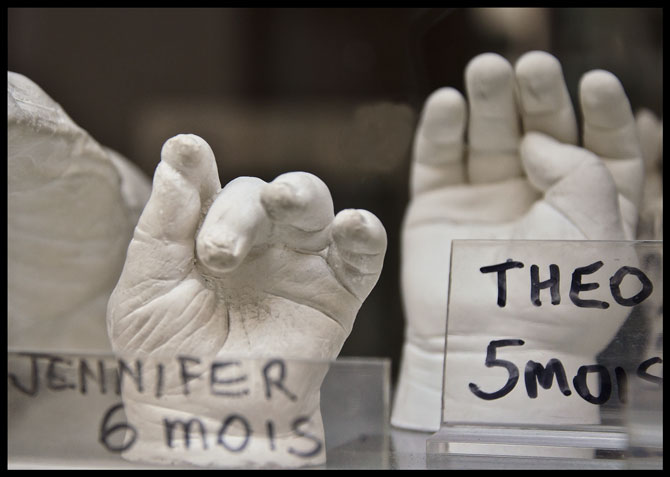

Before I die I want to welcome more grandchildren into our family.

Malika Moore

Before I die I want to be ready, as in Hamlet's saying, "All is readiness."

Polly Frizzell

Before I die I want to see my beloved sisters Kaaren and Jane in the flesh many more times.

Jon Hess

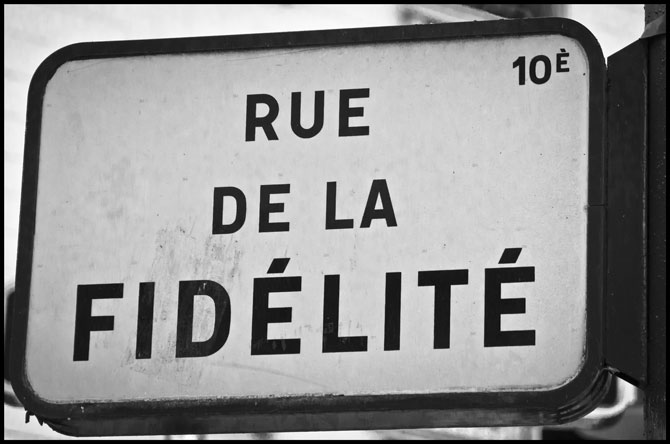

Before I die I want to be free to trust in love.

Aline Soules

Before I die, I want to know that I've lived completely.

Suki Edwards

Before I die, I want to explore Scandinavia and New Zealand.

Hope Alvarado

Before I die I want to go on an African photo safari.

Sojourner Kincaid Rolle

Before I die, I would like to have a poem that I have written acknowledged for its timeless perfection and, as its composer, be recognized in the history of our time as a Poet.

Marguerite Baca

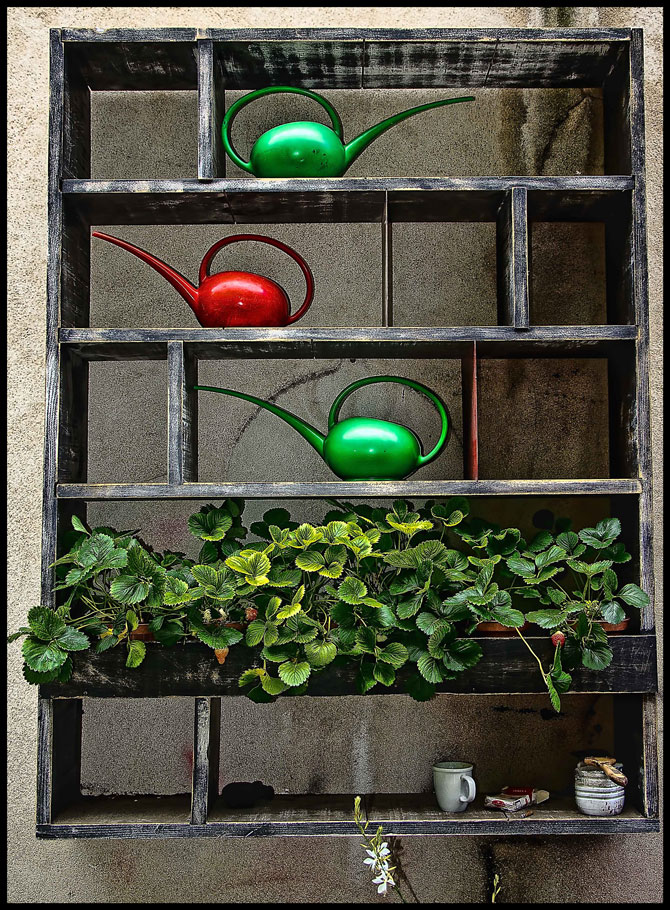

Before I die I'd like to develop a green thumb, if that's possible, and grow an abundance of vegetables and herbs to share with friends and loved ones.

Joanne Warfield

Before I die, I want to love as I've never loved before with every cell of my being until I turn back into stardust.

Daniel Abdal-Hayy Moore

Street art by Jérôme Mesnager

Street art by Jérôme Mesnager

Before I die, I want to breathe eternity's air, die before I die in the sweetest sense, and swim in its light.

Larry Colker

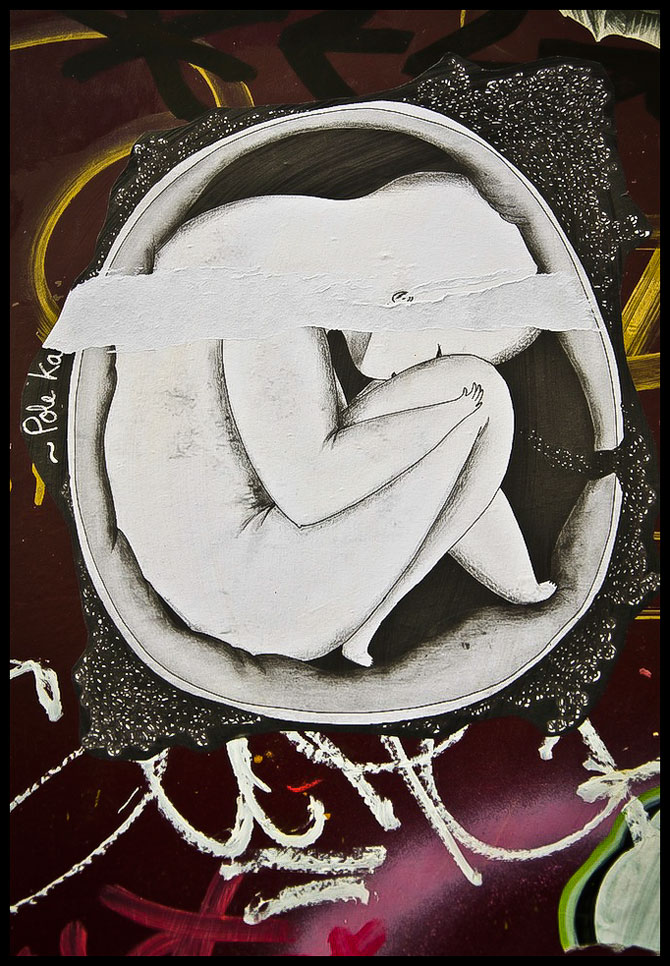

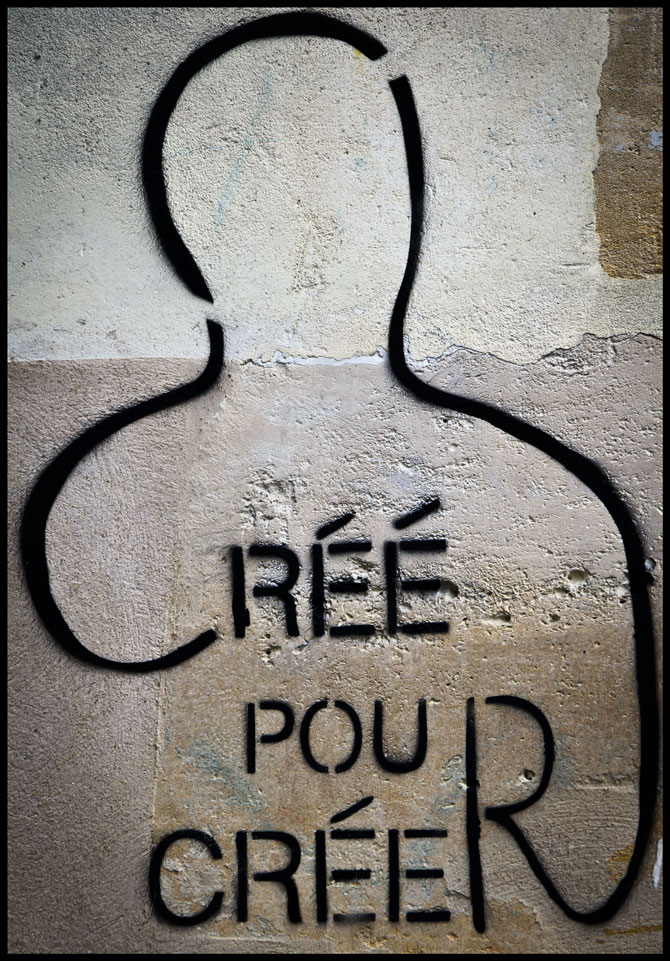

Street art by Pole Ka

Street art by Pole Ka

Before I die, I want to hold my great-grandchild.

Vivian Beban

Before I die, I'd just like to host a fantastic party for loved ones and friends, especially those I haven't seen in years, with a live band (my son-in-law Jeff being the leader, of course) and the best caterer money could buy, in a natural setting or a beautiful winery, and I'd want it to go on for a whole day and evening just like in the old movies.

Bayu Laprade

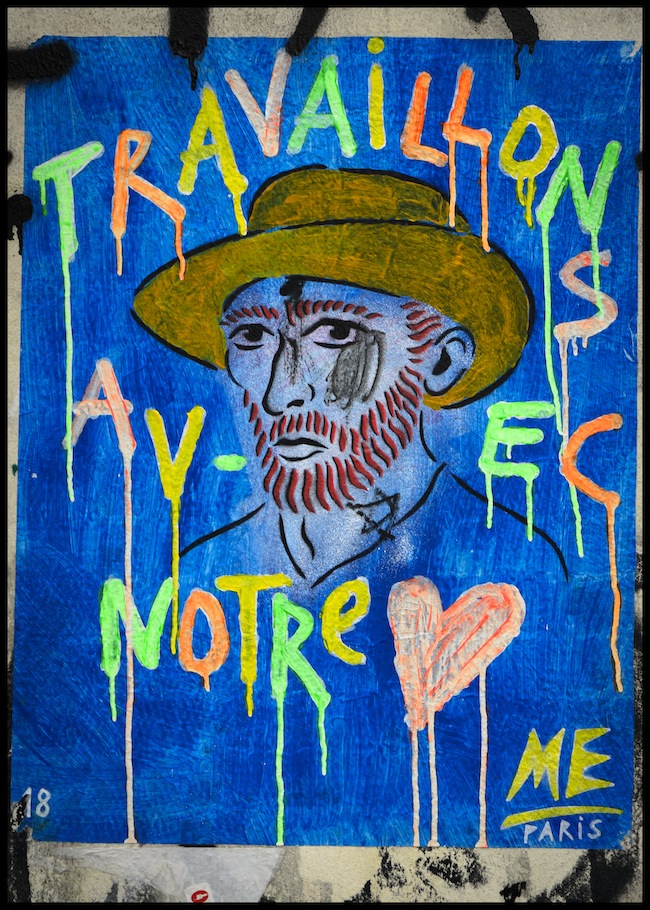

Street art by ME Paris

Street art by ME Paris

Before I die, I want to achieve great joy, success and mastery in a creative realm.

Sab Will

Before I die I want to know I made a difference.

Carol Cellucci

Before I die I want to stop working and travel.

Craig Fleming

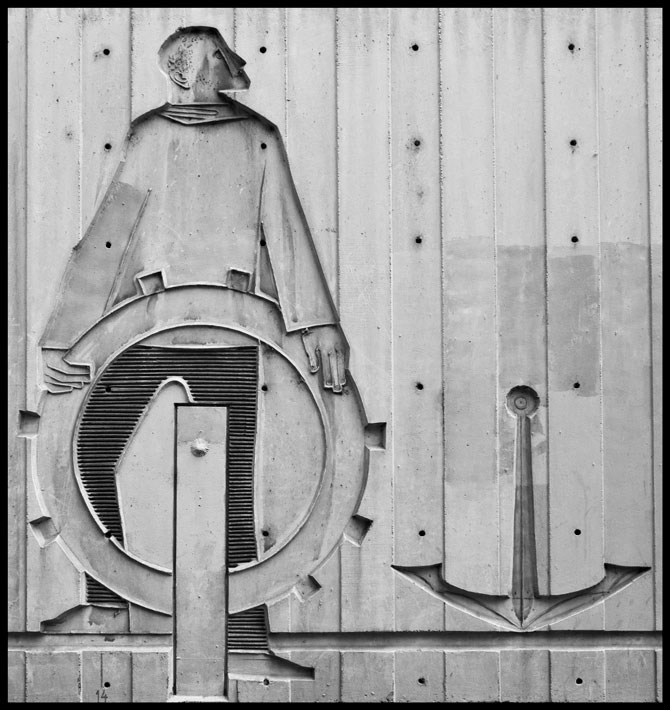

Before I die I want to whirl like a dervish on the razor's edge, entranced yet all the while fully awake.

Ebba Brooks

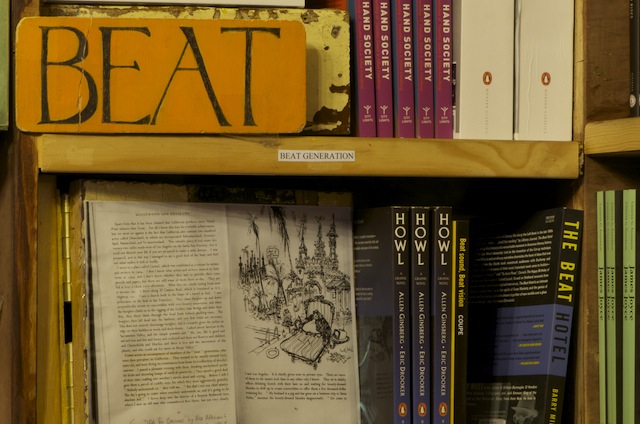

Before I die I want to get my novel published.

Kari Denk

Before I die, I want to know that my daughter is and will be strong, independent, happy, loyal, charismatic, loving, and an all-around good person.

Bruce Moody

Before I die, I want to bring my work before folks on line and clean out my basement so my daughter doesn't have to do it then.

Anonymous

Before I die, I want to...document every last piece of urban art in Paris.

John Brunski

Before I die, I want to go surfing as much as I did as a kid, or at least as much as my son does now!

Eric Schafer

Before I die, I want to have my book published.

Ren Powell

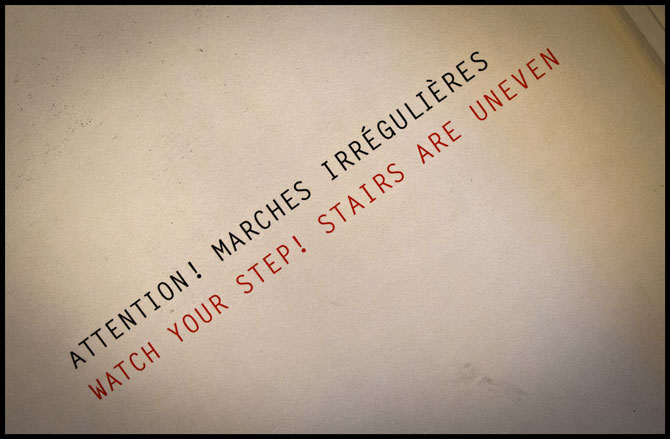

Before I die I want to grow very, very old slowly; to pass through my days like an outward-bound trip, seeing the new every moment.

Anne Reese

Before I die, I want to walk as I used to, or I want to walk well.

Connie Josefs

Create to create

Create to create

Before I die, I want to finish and publish my work.

Nancy Zafris

Before I die I want to spend an afternoon with the Loch Ness Monster.

Dawna Kemper

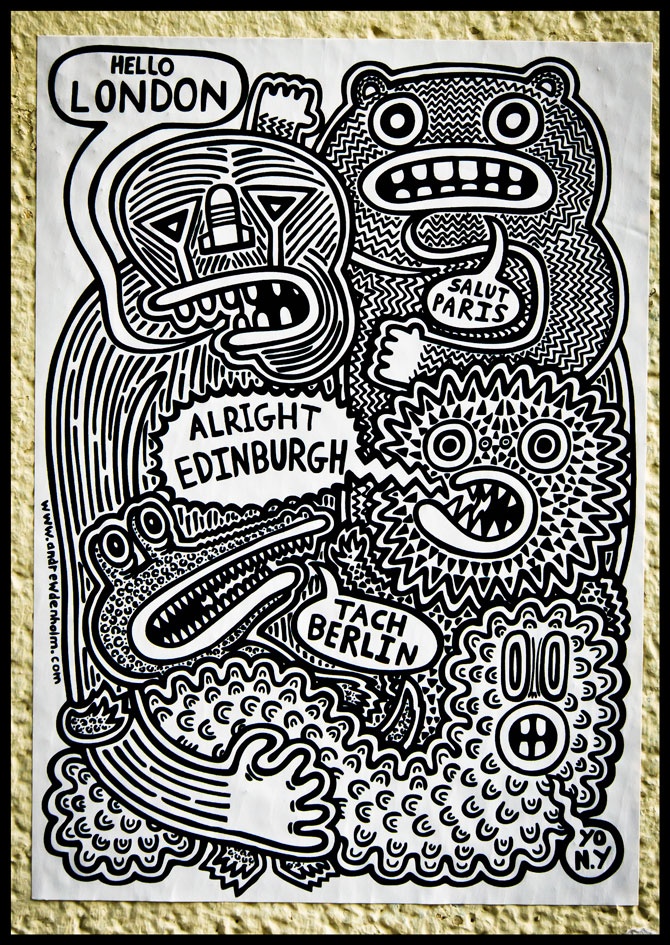

Street art by Fred Le Chevalier

Street art by Fred Le Chevalier

Before I die, I want to see a smart, soulful, progressive woman in the White House (as President, not First Lady; we thankfully already have the latter).

Kaaren Kitchell

Before I die I want to bring forth what is in me,

to transpose vision and memory

into literary works of art.

Betty Kitchell

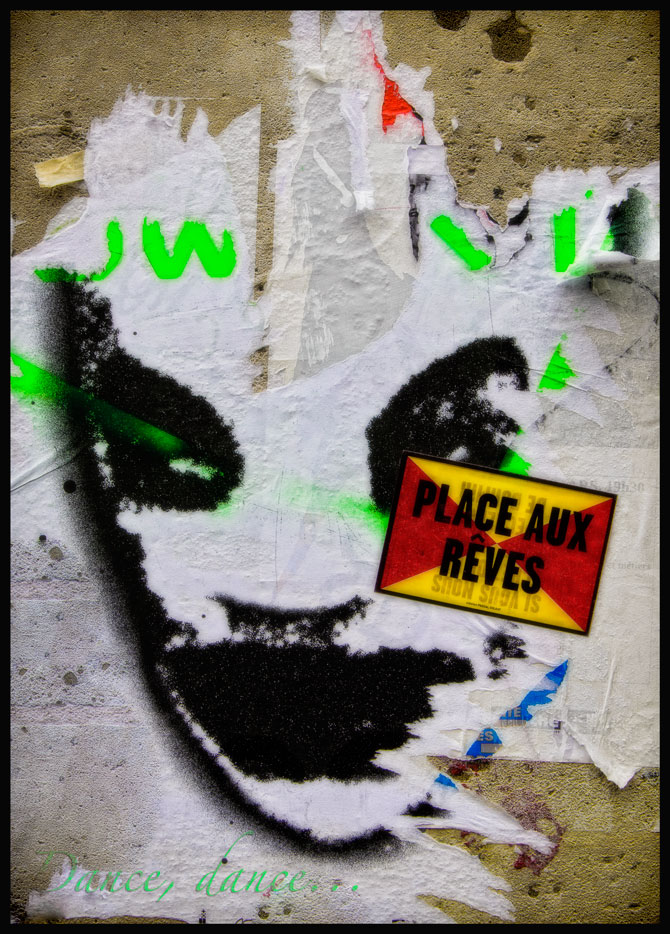

Street art by Sardine Animal

Street art by Sardine Animal

Before I die, I want to do…nothing! I've done it all!

Candy Chang,

Candy Chang,  death,

death,  dreams,

dreams,  friendship,

friendship,  surrealism,

surrealism,  wishes in

wishes in  Vision Quest

Vision Quest