We ventured so far into the inner world in the past two posts that I’d like to focus on something external this time, like, say, a list of differences between life in France and life in America. And why not present the list in the context of the vision quest? Those twelve sea creatures metamorphosed into variants of the Greek gods and goddesses, each with their own realm of action, so let’s look at the French and Americans through the eyes of the “invisibles.”

Any such list is entirely subjective, of course, coming as it does from our limited experience of living off and on for three weeks to three months at a time since the ‘80s and now as permanent residents of Paris for a mere three months. But here are a few things that Richard and I have noticed:

Poseidon (sleep, dreams, the Collective Unconscious)

We live in a stone building that was built in 1862. Our apartment is on the fifth floor and looks out onto two courtyards. We have three fireplaces, none of which work but which look good, especially the salamander in the dining room, and herringbone parquet wooden floors that creak when we walk but which we wouldn’t change for the world.

A salamander

A salamander

At night, if you lean out the window far enough, you can see the lights of every one of the twenty apartments in the two wings of our building. I am knocked out by the discipline of the French in relationship to sleep. By 11 p.m., almost every window is dark. By midnight, everyone has gone to sleep, including Richard and me…unless we are writing or editing photographs or studying French or we just got back from dinner with friends and are a bit too wired to sleep yet.

Beaujolais, the house cat at Rotisserie Beaujolais

Beaujolais, the house cat at Rotisserie Beaujolais

The French are our model for good sleep habits. They are Benjamin Franklin’s delight, “Early to bed, early to rise….” But we don’t always follow this model.

Dionysus (passion, desire, silence, the Personal Unconscious)

I’m going to get in trouble here, but here goes: We keep running into examples of the French notion that marriage and passion don’t go together. According to our French friends, mistresses and side men are rife, for both sexes. It seems to me that Americans place more value on fidelity in marriage than the French do. My advice to American women who are considering moving to France: find an American mate first, and move here together.

On the other hand, silence: we could write a book about the different public attitudes about noise in the U.S. and in France. It is shocking to sit in a restaurant surrounded by French couples or groups of friends who modulate their voices so that everyone in the room can have a private conversation; then a couple of Americans sit down and the shouting begins.

Or you fly back to the U.S. and land in NYC or Dallas-Fort Worth and before you’ve even reached customs, a TV overhead is blaring news or some inane reality show.

The relationship to silence seems to me to reveal something about a culture’s embrace of, or fear of, the soul. You cannot hear the voice (or voices) of the soul in the midst of a constant barrage of noise. Creativity begins in the soul.

And the French have a tremendous respect for creativity.

Artemis (emotional security, cleanliness)

Let’s just talk about showers. American showers are better, the plumbing is better, since it’s not hundreds of years old, the water has less calcium and it makes for less fly-away hair.

Then there’s toilet paper. Over the years, we’ve laughed at stories we’ve heard of people who bring a suitcase of their own, but it’s true, if you want sandpaper, go into any French bathroom.

I can’t speak about emotional security except one by one, within individuals. And I don’t know enough French individuals to say.

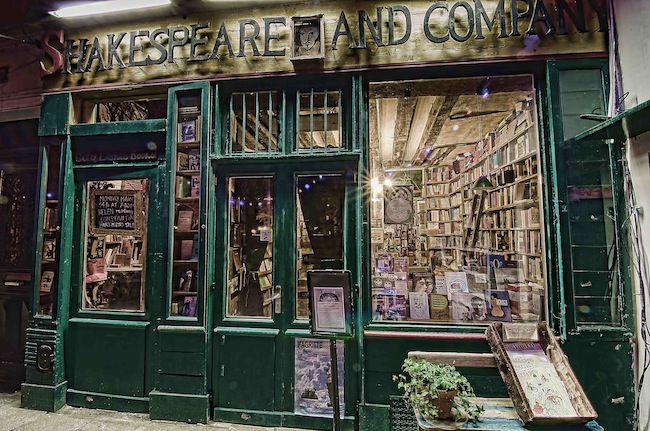

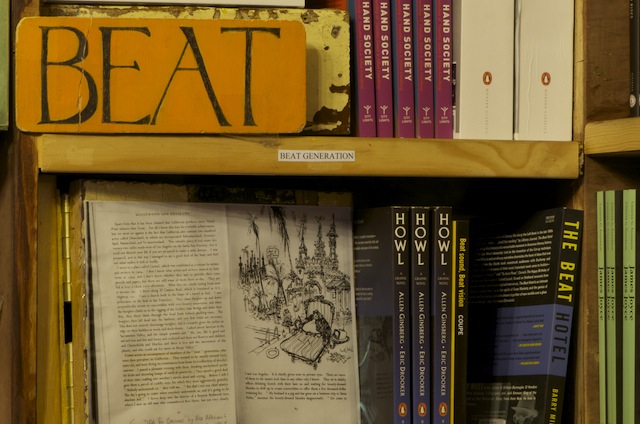

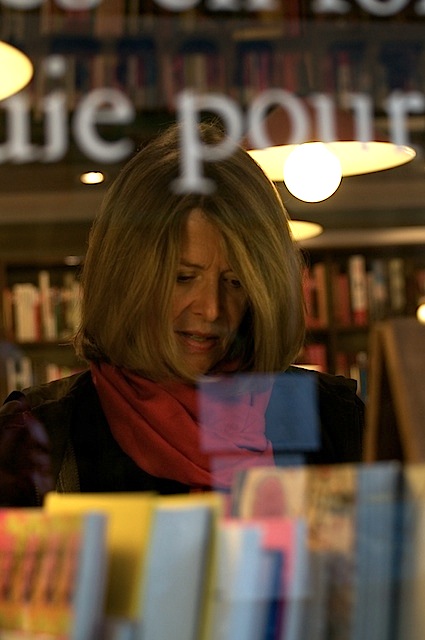

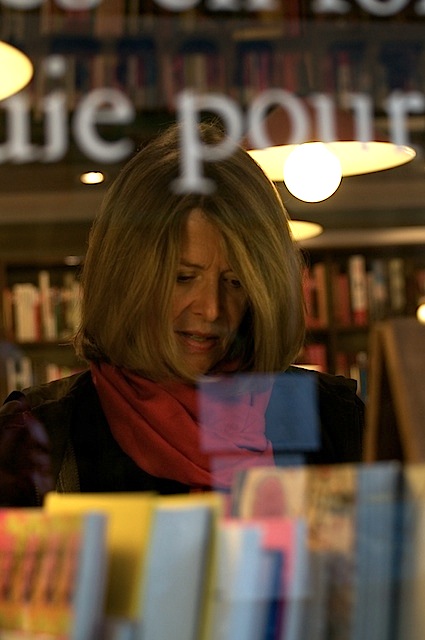

Hermes (education, reading, inspiration)

A friend just sent me an Internet link that compares how many independent bookstores there are in New York City to ones in Paris. The difference is staggering: something like 1400 in Paris versus about 18 in New York City. I’m not surprised. You can’t go for more than a few blocks in Paris without running into a bookstore.

“If you don't listen to the Guardian Books podcast, I recommend it. It's free. Regarding Montaigne, the podcast in Paris also distinguished the French, in contrast to the Brits and Americans, for loving and publishing essays, liking to read about ideas.”

Richard and I watch French TV for an hour a night, as one of our French lessons. It’s striking how many shows have intelligent debate about books, literature and ideas, and how few dumb sitcoms and idiot reality shows and dancing with celebrities there are. Our acupuncturist here told us how the American CBS series 60 Minutes did a long, admiring piece about the highest-rated show (at the time) on French television, an hour-long, prime-time Sunday night talk show called Apostrophes, which featured interviews with writers the caliber of Marguerite Duras and André Malraux. The show Apostrophes still has its own definition in the Larousse dictionary.

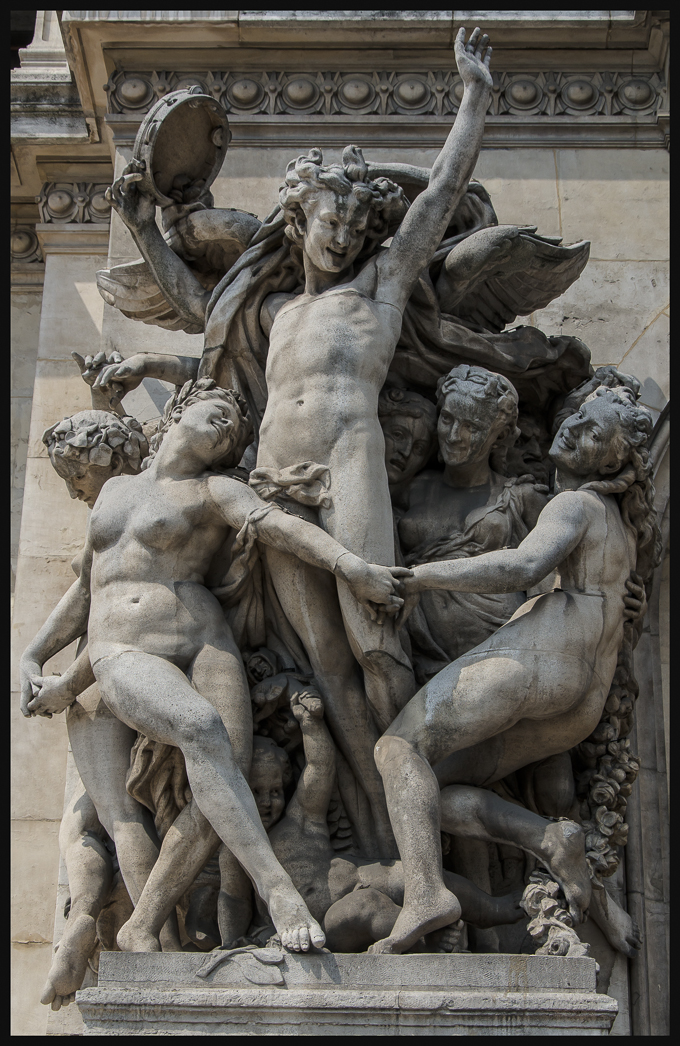

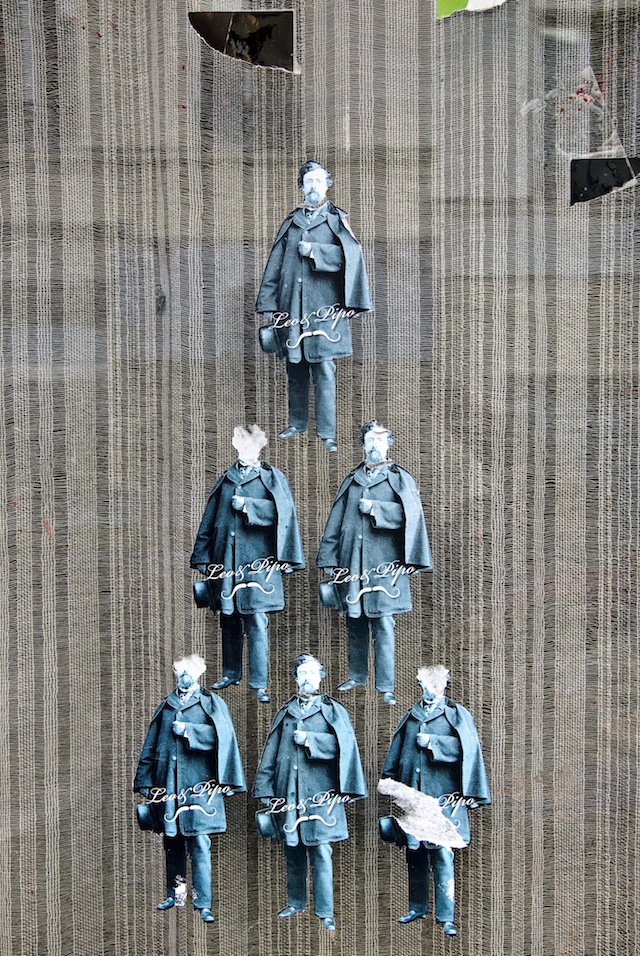

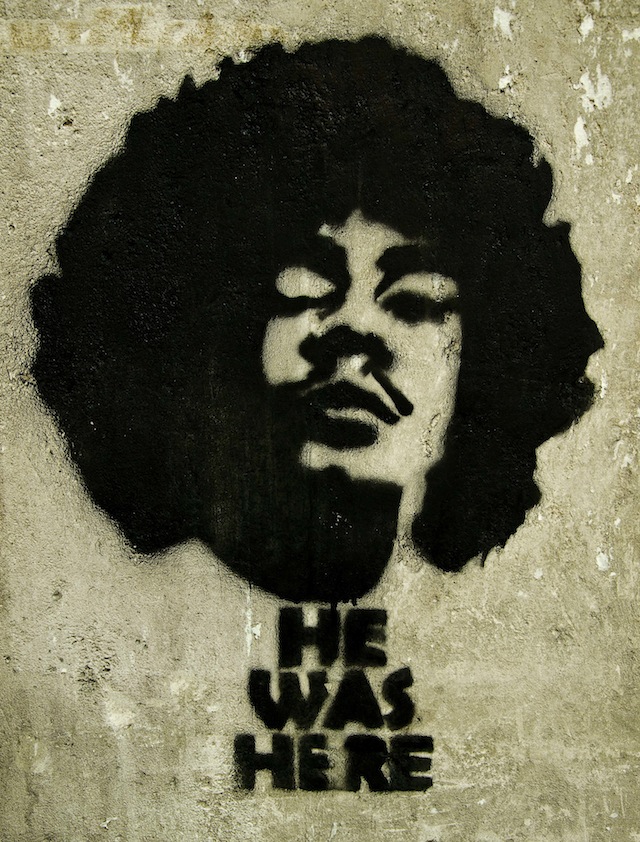

Daedalus (creativity, art, craft)

In this realm, there is something that is so striking about Paris that it might be half the reason we moved here: the street signs. You can’t go more than a block without reading some plaque on the wall that honors a poet, a novelist, a photographer, a sculptor, an architect, a scientist, a doctor, a philosopher. Often it is where that artist or inventor was born, or only lived for a year.

On our short street alone, there is a plaque at #74, where Hemingway and his first wife, Hadley, lived; a plaque at the town house, #71, where Joyce finished Ulysses in the apartment which was loaned to him by Valéry Larbaud, poet, novelist, essayist and translator; a plaque at #67 for the philosopher, Blaise Pascal, who died there in 1662; a plaque for Jacques-Henri Lartigues, the photographer and painter; and at #2, where the poet, Verlaine, lived for a time. Creative people are respected and honored in this city. Perhaps that’s why so many have lived here. You can feel it in the stones, in the buildings and in the streets.

Athena (government, management, money, peace)

It’s inevitable that a country such as France, which has known so many wars on its own soil, would be more cautious than the U.S. about invading other countries for imperialistic aims, whether to gain resources or territory (in the name of democracy, bien sûr). The U.S. is too young a nation, too naïve about the costs of war, to have much wisdom about the value of peace.

After divesting itself of its colonies during the wars of liberation in the early ‘60s, France has maintained liberal relationships with its citizens abroad, and immigration, while flawed (but at least they don’t build border fences), still rejuvenates French society daily. Most neo-logisms, which the French Academy tries desperately to keep out of the language, are now coming in from Arabic and African languages, not American English.

And money? The French pay about 70% of their income in taxes. Most entrepreneurial Americans would find that unthinkable. But they haven’t experienced the safety net—the infrastructure and the health care—that the French take for granted. More on the latter in Demeter’s realm.

Hestia (house, home, garden, interior and architectural design)

Parisians live in apartments with fewer square metres than the average American. We moved from a house of 2,500 square feet to a 900 square foot apartment. While there’s no room for all of our books, it is considered relatively roomy by Parisian standards. And we immediately have a more expansive life here than when we lived in a larger house. We can walk anywhere in the city and join friends in restaurants that are open to the street, or to any one of the theaters you find every few blocks or any of the world-class museums to be found within walking distance. Imagine, a troupe of world-class Sufi dancers from Syria performing two blocks from your apartment.

But “home” brings me to another subject: household appliances. Americans win that one hands down. We cannot figure out why a European Maytag washing machine takes several hours for a load of washing and several hours for a drying cycle and is noisier than the jets coming in and out of LAX. It’s a mystery. But Americans are better at manufacturing machines.

Aphrodite (beauty, morphos, shapeliness, style, love)

Paris is the center of fashion, so fashion is in Parisians’ genes. What is striking, in contrast to the outlandish styles you see on the fashion runways, is how French elegance combines three things: fine material, simplicity of design and understated refinement. And it seems that mini-skirts never go out of style here, they’re just accessorized with leggings or dark stockings in the winter.

And shapeliness? It’s startling how few fat Parisians you see. This is due, we think, to the nourishing diet, and to the ease of walking in Paris.

The French seem to have built-in radar for temperance and restraint in standards of beauty. You rarely see huge artificial breasts, bad face-lifts, over-bleached hair, sloppy gym clothes in the street and men who dress like boys in shorts and T-shirts—again, elegance seems to include the notion of measure and appropriateness here.

And love? Aside from food, it’s the national religion.

Demeter (food, cooking, nourishment, health)

No one who’s ever spent three days in France forgets the food. The bread! The cheese! The chocolate! The artistry and deliciousness of the cooking!

Poilâne bakery, the world's best

Poilâne bakery, the world's best

But let me just mention what the French lack: Whole Foods. There is no market like Whole Foods in Paris. I miss the American spicy salmon and California guacamole they sell. And though the French make a better almond butter, they can’t approach American peanut butter.

Then there’s health care. Our health insurance payment here is equivalent to our old Anthem Blue Shield, but it pays for all medicine, all doctor visits, and a doctor’s visit means the doctor comes to your house if need be. But we wouldn’t want any such socialism in our country, would we? Well, maybe if we’d experienced French health care, we might.

Ares (goods, shopping, purchases, travel, war, practical community protection--such as firemen and policemen)

In spite of my fondness for Whole Foods, it is so soulful to walk to the boulangerie to buy bread freshly baked within the hour, cheese from a fromager where every clerk knows the history of fifty different kinds of cheese and what bread or wine would go best with it. And if you’re a chocolate kind of person, you can buy that dark chocolate and carry it out in a turquoise bag that is more beautiful than a bag from Tiffany’s.

And the public transportation? It makes us weep with gratitude. Though most of the time we can walk to just about anywhere in the city (Paris is only 41 square miles, smaller than San Francisco), when it’s raining or very late, we can hop on a Métro and reach any distant destination in the city within 40 minutes at the most. After driving for hours at a time to get to a destination in Los Angeles, this human scale, of buildings mostly not much taller than five stories, of restaurants and shops mixed in with residential apartments, of great public transport, everything feels intimate here. And that has a relaxing, pleasurable effect on the psyche.

As far as protective services, my hairdresser in Los Angeles, who was from Paris, told me that after experiences like being occupied by the Germans in World War II, the French will not put up with aggressive local policemen. He said we’d get to know the police in our arrondissement, and run into them at our local cafés, and get to know them by name. And that compared with American policemen, they’re much friendlier, and less confrontational.

We experienced this when Eric, a policeman, was called to our building. He was a blond young man on a bicycle who seemed about as threatening as the pre-med student in your dorm in college. (But that’s another story.)

Apollo (performance, enjoyment, celebration)

Okay, here’s a story from 2009. Richard and I went to see Martin Scorsese’s film about the Rolling Stones, “Shine a Light.” It was in one of the theaters in what used to be the former public market, Les Halles, a rather Dionysian part of town near the rue St. Denis, where all the hookers hang out. The theater was full. We had good seats in the center of a central row. Now, no one goes to see a film about the Rolling Stones unless he or she likes rock ’n’ roll, and has some attraction to the Dionysian brand that the Stones have been giving us since the ‘60s.

The film was terrific. One great song after another by the greatest rock band in the world (And if you disagree, you’re just wrong.) We could hardly sit in our seats we were so ecstatic. Richard was once a disc jockey in the San Francisco Bay area, and we both came of age with the great rock bands of the ‘60s. It was crazy to be listening to this music and sitting down. So we moved in our seats. How could you not?

But we slowly became aware of the oddest phenomenon. Everyone around us seemed rapt. No one was leaving the theater. But everyone sat, not moving, hands in their laps, like good children waiting to be allowed to eat. No one around us even moved their heads slightly in time to the music. We wondered if we’d hear people saying afterwards that they hadn’t liked the film or the music. But no, in the lobby, we heard low murmurs of approval in French in every direction. We stood by the exit door and listened. The very thing that makes it so pleasant to be in a public space with the French, their decorous restraint, seemed lunatic while listening to the Rolling Stones.

We came away with two impressions: that Americans with their impulsive exuberance might just know how to let loose better than the French, at least in public. And this is why great rock ‘n’ roll has come from England and the United States and not from France. It’s just not the gift of the French.

Zeus (generosity, gift-giving, blessing)

The uninhibited nature of Americans makes it easier for them/us to express generosity. Or so it seems to us at this point. Though, as we get to know more French people, who knows what we’ll find? The French, we are told, are notorious for their initial reserve—smiles are earned, not given freely as they are in the United States. But, we are also told, they are warm life-long friends once you break through that reserve. We’ll keep you informed.

03.11.2013

03.11.2013