A Eulogy for Jane Winslow Eliot (9/27/26 — 7/31/2011)

10.8.2011

10.8.2011

9-15-11

Time and space do not exist.

I heard these words as I washed the breakfast dishes this morning.

I was thinking of Jane Eliot.

It had been just over 40 days since she died.

I wanted to try in meditation to accompany her through the bardos.

But I couldn’t.

Maybe it’s that I do not experience death the way that Tibetan Buddhists do.

Or maybe to some extent I do, but I don’t have the inner stillness to stay on that journey for long.

Or maybe my sense is that Jane had already moved through a panoramic review of her life while she was alive.

I remember her deep honesty in her memoir, “Around the World by Mistake.”

9-19-11

It’s extraordinarily difficult to say who someone is, to approach describing their identity.

What is her effect on you? Is it lightening? Darkening?

Does he give you energy? Take it away?

Maybe we know others mainly through their effect on us, inspiring or disheartening.

Richard and I came back to Paris from the joyful celebration of our friends’ Loire Valley wedding, and heard from a mutual friend that Jane Eliot had died.

It often seems to happen this way. A great upsurging of joy, then sadness, sorrow breaking through.

I left out what happened at our wedding in Crete. Alex and Jane had encouraged our notion of being married there, because Ancient Crete was one of the last partnership cultures.

During our wedding dinner, one of my relatives said to our friends that she wished their oldest daughter had been there. Both parents were storm-tossed with sorrow at her sudden death in her early 20s. Steve wept at the table. Rain ran into the nearest bathroom. Some of us followed her. Some of us comforted him.

And one of my family said, softly, “Oh, I wish they hadn’t ruined the celebration this way.” But no, I thought, and said, There are always these parallel channels of grief and joy. The day is richer for their tears.

And Jane Eliot? Her death was different. Her life was long and rich, fulfilled.

I’m circling and circling my memories of her.

Whatever you brought to her, she greeted it, surrounded it, examined it, enlarged it or lovingly tossed it away, laughed or seriously addressed it.

9-20-11

I’m circling and circling memories of her:

In the very first week of blossoming love between Richard and me, when we discovered that we lived only four blocks from each other in Venice, California, he invited me to a neighborhood block party at the home of his friends, Jane and Alex Eliot.

There was an odd symmetry to where they lived in relationship to Richard’s place. He and they each lived in a house on the same block of Paloma Avenue, each one house away from the end of the block.

The block party was the first social event, besides the poetry readings where we’d met, to which we’d gone as a couple. Jane and Alex, a generation older than we, instantly became the couple with whom we were closest.

What did we talk about at this party? Not the neighborhood. We talked about our love for myth. Alex had written a number of books on myth. We talked about the mythosphere, a term Alex coined for the place where myths live, where the stories of the soul dwell.

In those first days of our new life together, Richard and I discovered much about one another through the mutual passions we shared with Jane and Alex: mythology, especially Greek myth, Greece and the Greek islands, Venice Beach, poetry, art, a marriage of kindred souls that included lively spiritual and intellectual dialogue, writing, room for solitude for writing, as well as for romance, a contempt for mean-spiritedness.

We laughed at the same things, especially dumb, pompous human behavior and dismissed the same things as a waste of time.

We saw each other at our home for dinner and parties, and at theirs for the same. Jane’s specialty was a smorgasbord of meze.

We met at Figtree’s Café on the beach for breakfast, or the Rose Café for lunch or Lula’s for Mexican dinner.

During the three years that we and three friends ran a weekly poetry reading series at the Rose Café, I don’t think Jane and Alex ever missed a single reading.

When I think of Jane, I hear her laughing—a merry boisterous laugh which delighted in generosity, surprise and beauty, and had a touch of scorn for human idiocy.

Jealousy? She understood that she was unique and so is everyone else.

Jockeying for power? She and Alex had been at the pinnacle of power in New York City and gladly given it up for creative freedom and time.

Greed? What does anyone need beyond food, shelter and time for love and creativity? And adventure!

Snobbery? She didn’t see people in hierarchical terms at all, much like my father. If you are really aware of each person’s uniqueness, how can you put anyone above you or below you?

Unkindness? A sure sign of unkindness towards oneself.

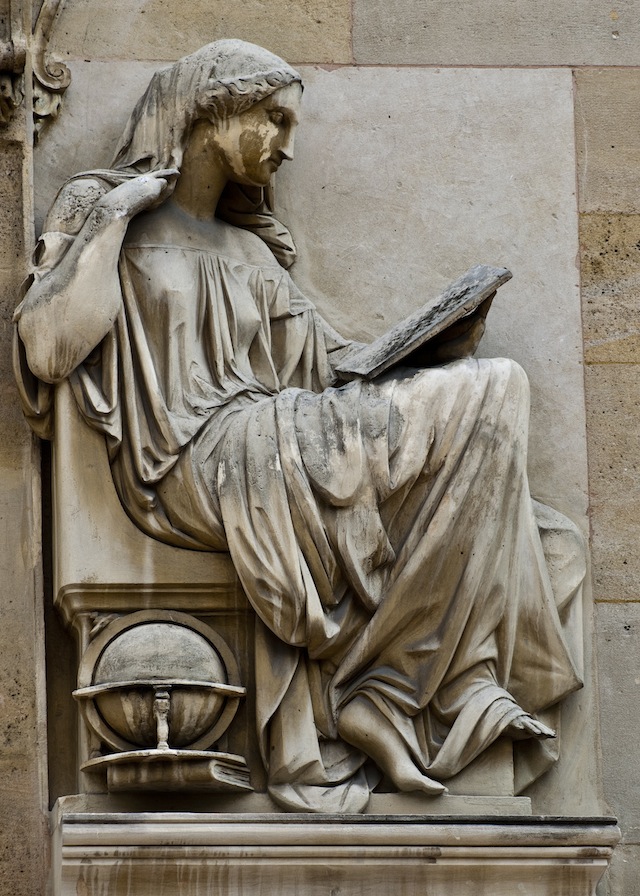

I called her Athena. She was a Libra, and shared that sign’s affinity for the goddess of peace, earthy intelligence, inventiveness and fierce strength. Nike!

Wherever you walked with Jane, she exclaimed over the beauty of her natural surroundings—birds, trees, the sea.

Well into her 70s, she’d walk down Paloma several blocks for a swim in the Pacific Ocean, which is colder on winter mornings than you can imagine. (Or so I hear.)

What Richard and I loved best to do with Jane and Alex was to sit at Figtree’s or the Rose Café (whose names, naturally, come from nature) and talk. Really talk. Talk that ranged all over the world—the earth and her creatures, humans they had known—Dali and Gala, Frida and Diego, for starters, or their noisy neighbors—and spirits of the mythosphere.

To Jane, the invisibles were as real as birds, as people. You felt relieved in their company to escape the tiny cage of rational materialism.

With Jane—and Alex—I could talk about the mythical vision I’d spent years discovering. When Richard and I shaped our combined mythical knowledge into a workshop at the C. G. Jung Institute, Jane and Alex were in our first class of students. (Oh, the irony, "teaching" these two masters of the mythosphere.)

Alex and Jane had lived all over the world, been top journalists in NYC. She had worked at CBS for Edward R. Murrow and at Time magazine; he had been Art Editor for Time, until his pension and a Guggenheim Fellowship allowed him to retire early and take his family to Greece. For four years they’d lived in Greece with their two young children, writing, home schooling the children, and exploring sacred sites.

There was only one respect in which they seemed to be bound by the conventions of their generation. Alex continued to write and publish books on art and myth, and now was working obsessively on a poetic memoir.

Yet she, when we first met them, was not as disciplined a writer as he.

She had published a book on children’s education, Let’s Talk, Let’s Play and written a highly original cookbook, Beyond Measure; A Cookbook for People Who Think They Can’t Cook, and published other books and journalistic articles in such magazines as The Atlantic, Smithsonian, Horticulture, Travel & Leisure.

But the assumptions of her generation mostly held: the woman would care for the home, children and relationships, while he worked.

Yet you could hear in the leaps of imagination, the sensory precision of Jane’s conversation that there was a longer story she needed to write.

And then she suddenly did it: created a studio for herself on the top floor of their duplex (so that was why she never managed to find the right tenant), and wrote, edited and published her memoir, Around the World by Mistake.

The title delighted us, containing all her qualities of humor, adventurous spirit, trust in serendipity, and largeness of experience. And the story itself unfolded in sparkling, sensuous prose, a vivid sense of weather and the sea, absolute clarity about others’ character, and the most brilliant example imaginable of how to inspire children.

The memoir tells the tale of how, in the summer of 1963, the couple, with their two young children, signed on for a trip around the world. The Yugoslavian freighter was scheduled to deliver goods from Yugoslavia to Osaka and back, a trip of seven months with sixteen passengers. But this is no ordinary trip. They discover that they are in extraordinary danger. But I won’t spoil the story, when you can order it and read it yourself. That’s Jane on the cover with a seagull on her head.

And then, Jane listened with great sympathy and understanding to my account about the last few years of my father’s life, his deepening dementia. She understood my longing to stay connected to his soul, beneath the dismantling of his rational mind.

And she rejoiced with us that my father was able to die at home, most certainly aware of his family’s love.

Jane’s mind, which was so alive, original, and warm—began to fade a few years after my father’s death in 2006.

By then, we had moved to Playa del Rey. In the sad way that driving distances separate people in Los Angeles, we saw Jane and Alex less often. They didn’t like to drive at night. One of us didn’t like to drive at all.

We’d bring dinner to Jane and Alex’s or meet at the Rose Café. Her mind wandered in conversation, but Alex, and we, assured her that it didn’t matter, she was still Jane.

And when we walked back to their house on Paloma, always, always, she pointed at birds, trees, the sea, with love and glee.

She was my wise woman. Magnificent Jane.

After the first sorrow, after the tearful call to Alex, a strange thing happened: I haven’t mourned Jane at all. It’s as if she hasn’t died. She is present, alive, vivid, much as my father continues to be.

Honestly, I don’t think we know a single thing about death. All I know is that Jane is still here, and oh, how we loved her. How we keep on loving her.