Hestia: Home, Sweet Home (News from the Mythosphere, Part Three)

12.9.2011

12.9.2011

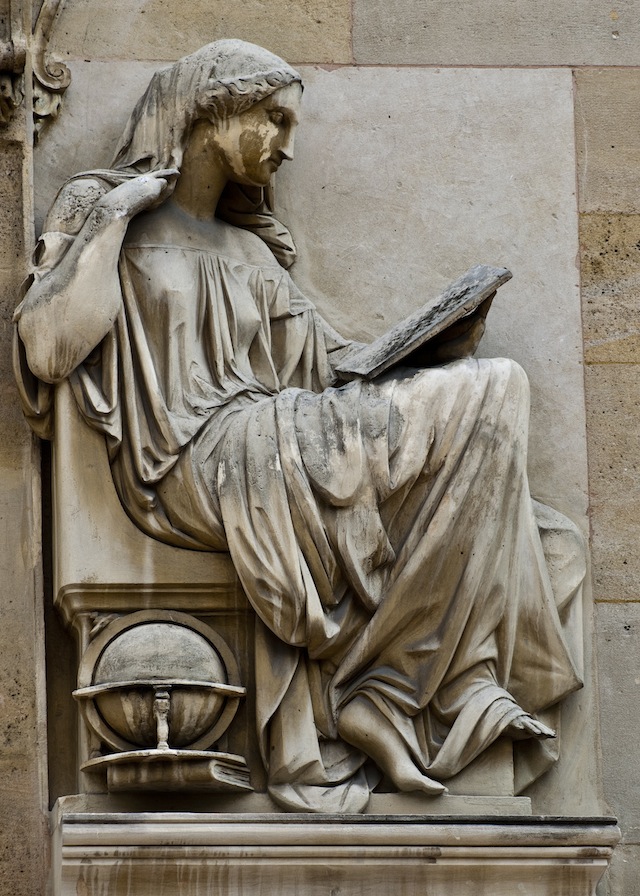

We’ve been at it for over a week. Trying to persuade the goddess of the hearth, Hestia, to tell her story to you in her own words. She simply refuses. The gentlest, most modest of all the Olympians, she never gets involved in disputes or wars. It’s so like her not to want the spotlight on her.

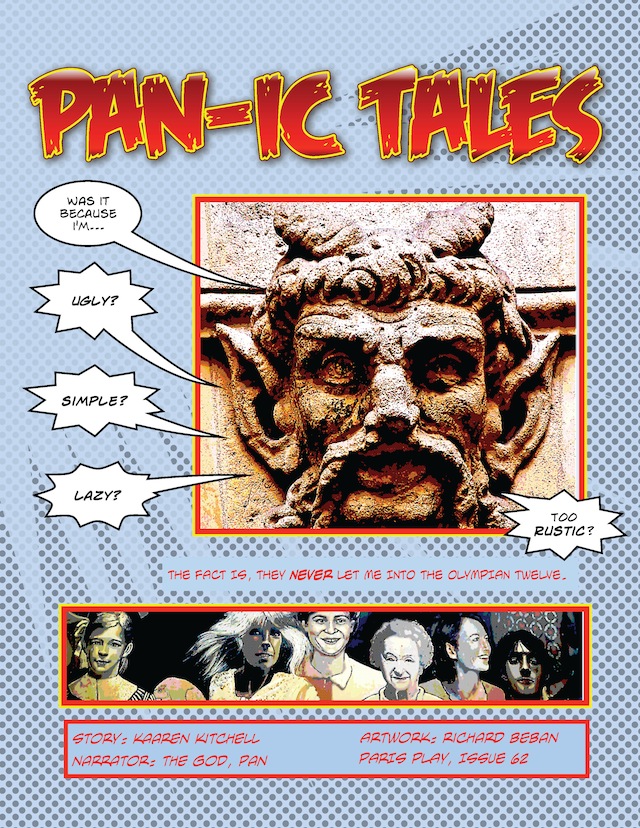

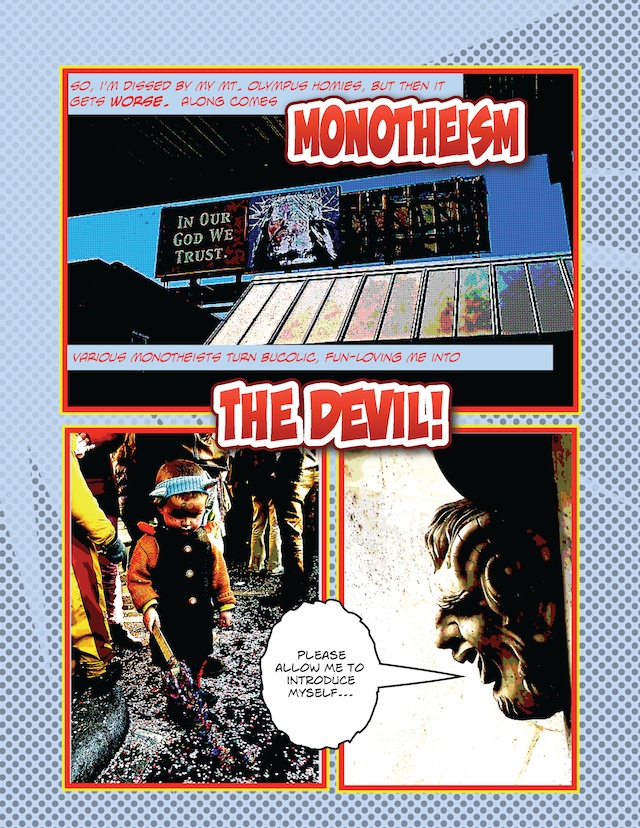

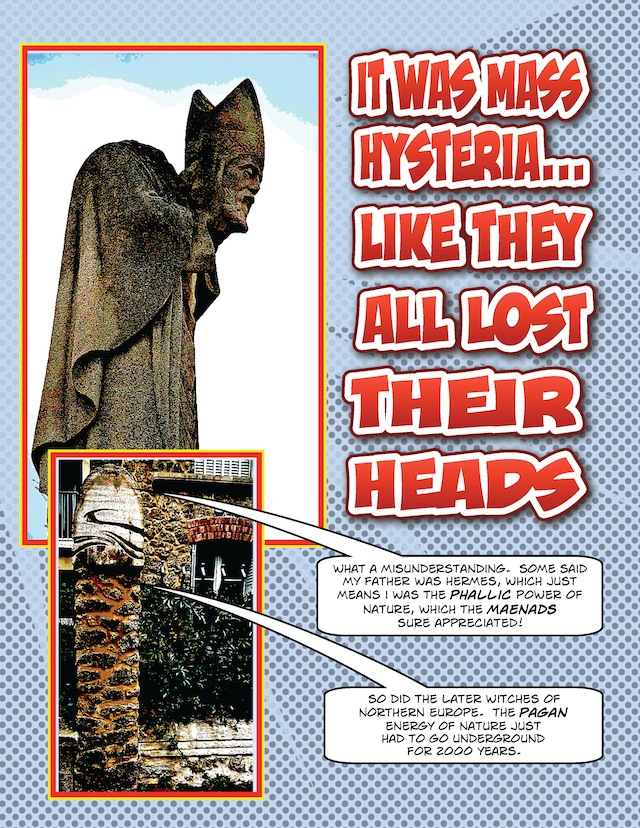

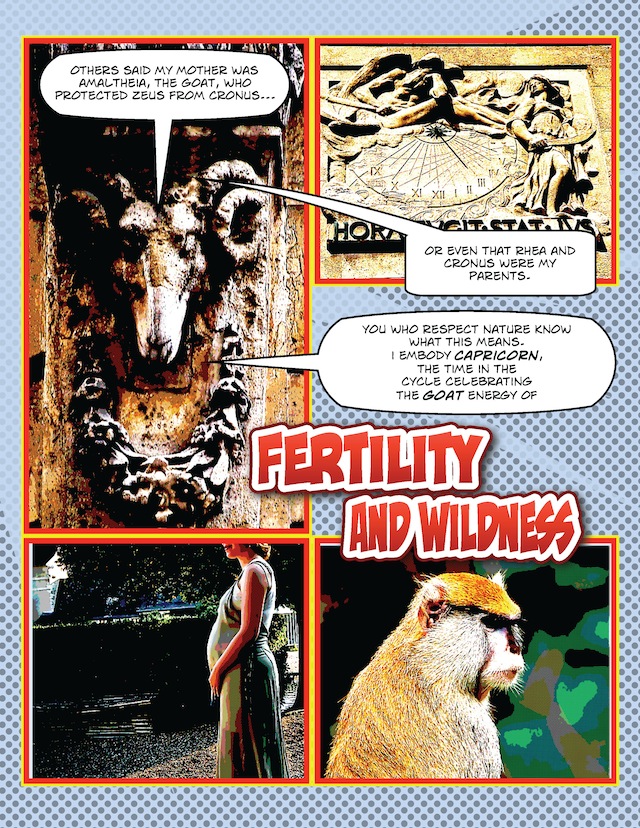

But that means that we’ll have to relay her story to you ourselves. She had a few things to say about Cronos (see Part One) and Pan (see Part Two). In her most tactful, fair-minded way she reminded us that there is a positive side to Cronos (or Saturn, as we call him out in our Solar System) and a dark side to Pan.

Here’s what she said about Saturn: He’s not just the tyrant Holdfast. He’s also discipline, hard work, slogging along in spite of not being in the mood to work. He’s the necessity for boundaries, limitations, frugality. He is the balance to Zeus’s expansiveness, and he’s necessary to all of us in order to stay grounded. He is what that ancient Chinese book of wisdom, the I Ching, means by "Perseverance Furthers."

Then she told us the female side of the story of all those women that Pan ravished. She reminded us that when humans lived in caves, they had little protection against attack. Women, especially, were at the mercy of male lust.

Hestia stepped in at that point and introduced the art of building houses. A house, she said, served not just to protect humans from the elements, but also to protect them from dangerous animals and more malicious humans.

A home is a central element of security and peace, she said. As the goddess of the hearth (the central fire in every home and city hall), Hestia guaranteed protection to anyone who came to her for aid. Hospitality was sacred to her.

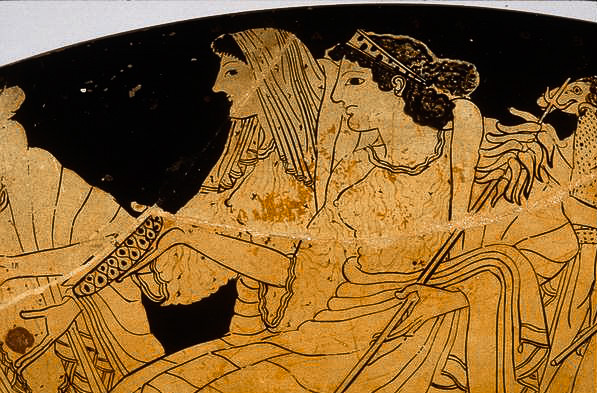

The sequence of stories in ancient Greek myth is revealing: first Cronus is defeated. Then, on Olympus, both Poseidon and Apollo seek to marry Hestia. But Hestia swears by Zeus’s head to remain a virgin forever. As a reward for keeping the peace on Olympus, Zeus allots to her the first victim of every sacrifice.

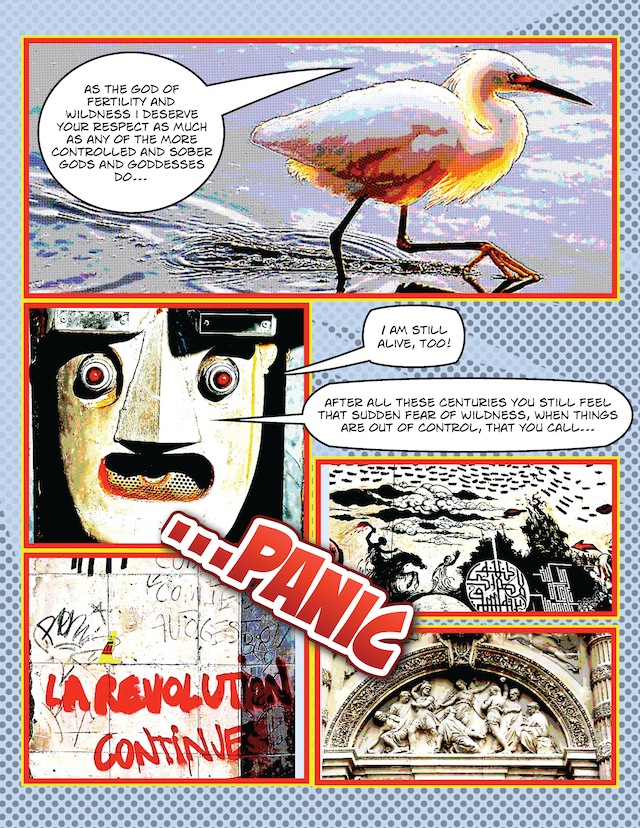

Later, at a rural feast with all the other gods and goddesses, everyone falls asleep after feasting. When Priapus, drunk, tries to ravish Hestia, an ass brays, and awakens her. Priapus runs away in fear.

Because the ass symbolizes lust, the story is a warning against the sacrilegious treatment of women who were under Hestia’s protection.

So, what do Cronus and Rhea, Pan and Hestia, have to do with what’s going on in the world right now, and in particular, the Occupy Movement?

If Cronus is tyrannical repression, and Rhea is Mother Earth, and Pan is riot, and Saturn is constriction, and Hestia is home, how do all these spirits interweave to explain our current zeitgeist?

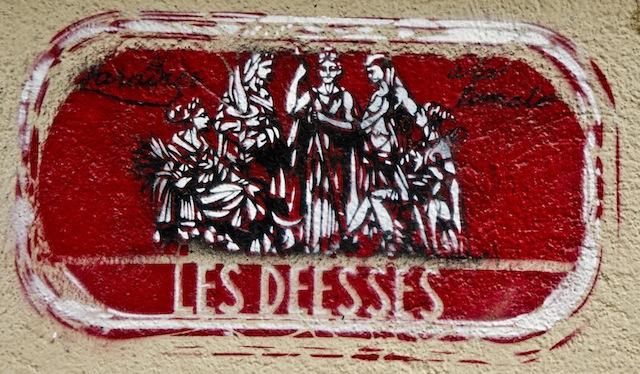

The hint is in the stories themselves. The ancient image of the Great Goddess (all the subsequent goddesses were aspects of the Great Goddess) was a white aniconic image (i.e., not in animal or human form, rather suggestive, of gods), which may have represented a heap of burning charcoal coated in white ash, which was both the method of heating in ancient times and the center of gatherings of the family or clan.

At Delphi, the charcoal heap outdoors was called the omphalos (navel of the earth) and inscribed with the name of Mother Earth. The charcoal heap was placed on a round, three-legged table painted red, white and black, and the Pythoness prophesied from the fumes of burning hemp, barley grain and laurel. We know that Hestia is a later manifestation of Mother Earth by the fact that both have the sacred hearth, both for prophecy and the home fire, as central images.

The Great Goddess had prophetic powers. So we turned to her to interpret today’s unfolding events. Here’s what she whispered to us: Just as we move every month through one zodiacal animal or human, so we move every decade through one of the circle of the constellations. In this decade, in 2011, we have moved out of the abundance and expansiveness of Zeus’s decade, Sagittarius, the ‘00s or aughts.

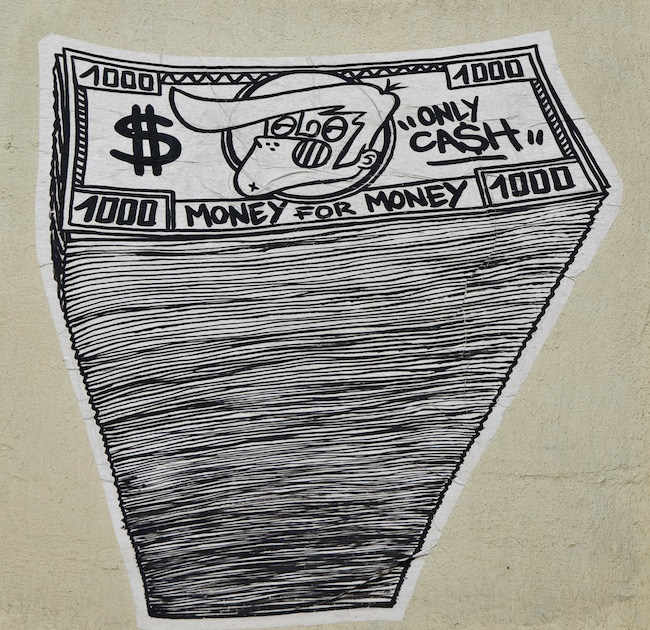

The stories of our current decade come from the myth of Capricorn, one of the four zodiac signs concerned with security. The contraction of the sign is mirrored by the economic hardships unfolding on the world stage. Tyranny, limitations, riots, constriction, the housing market crash, and the dangerous state that Mother Earth is in. In another, previous earth decade (the 1930s, Taurus), we experienced the hardship and tumult of the Great Depression. In the most recent earth decade, (the 1970s, Virgo), we experienced oil shortages and recession.

In the three earth decades, we are reminded of the limitations of physical life. In this decade, we’re being challenged to learn to live more simply, more frugally, and, in the face of unwise governments shredding social safety nets, to share available resources with one another.

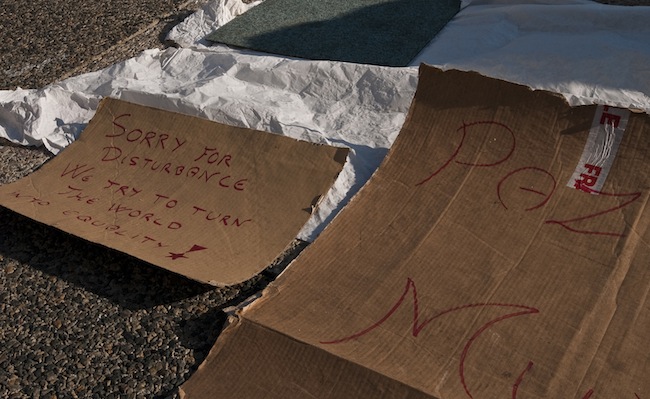

Home: On the world stage, isn’t all this rioting for democratic rights and justice really a fight for the right to work and protect the security of families and homes?

Home: In the U.S., doesn’t it make divine sense that the Occupy movement is now turning towards occupying foreclosed houses? As Ryan Acuff of Take Back the Land in Rochester, N.Y. says, they are taking direct action to make housing a human right by matching people-less homes to homeless people.

Home: MSNBC's Rachel Maddow offers this fine eight-minute video comparing the Occupy Foreclosed Homes movement to similar events in the ‘30s:

As a man interviewed in a Take Back the Land in Rochester video says, “Today I’m going to be warm. Today I’m going to be fed.”

Home: Don’t we all deserve homes?

Home: Isn’t it time we cared for Mother Earth?

Let’s go back about 150 years to the English art critic and social thinker, John Ruskin, who coined the word “illth,” in contrast to our word, “wealth.” Ruskin envisions wealth in its largest sense, of abundance and well-being in every part of human life and the life of our culture and planet Earth. Illth, then, is the reverse of wealth, its absence, ill-being. Illth means various devastations and trouble in all directions.

And we are in a world-wide cultural and planetary state of illth.

Finally, let’s go back to the seventh or sixth century B.C. to Ancient Greece, and listen to how a Homeric poet envisioned wealth, in this Homeric Hymn to the Earth Mother:

TO EARTH THE MOTHER OF ALL: I will sing of well-founded Earth, mother of all, eldest of all beings. She feeds all creatures that are in the world, all that go upon the goodly land, and all that are in the paths of the seas, and all that fly: all these are fed of her store. Through you, O queen, men are blessed in their children and blessed in their harvests, and to you it belongs to give means of life to mortal men and to take it away. Happy is the man whom you delight to honour! He has all things abundantly: his fruitful land is laden with corn, his pastures are covered with cattle, and his house is filled with good things. Such men rule orderly in their cities of fair women: great riches and wealth follow them: their sons exult with ever-fresh delight, and their daughters in flower-laden bands play and skip merrily over the soft flowers of the field. Thus is it with those whom you honour O holy goddess, bountiful spirit....Hail, Mother of the gods, wife of starry Heaven; freely bestow upon me for this my song substance that cheers the heart!

Occupy Paris

Occupy Paris