Open Minds

12.14.2012

12.14.2012

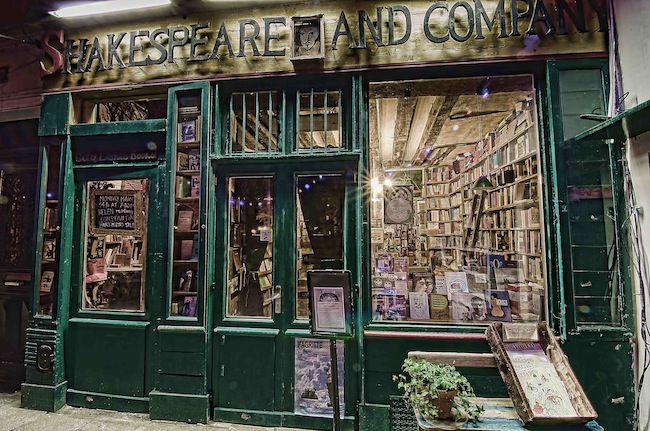

I was full of inspiration after the evening panel discussion by French, British and American literary magazine editors at Shakespeare and Company Books. I wanted to get home quickly to open my new books (Giovanni’s Room! The Stockholm Octavo! The Tenants of The Hôtel Biron! Londoners! Tin House’s issue on Beauty!). But I was hungry. I took a short detour down one of those twisty golden Paris streets to a little Italian trattoria with phenomenally tasty pizza.

The small black-haired Italian girl behind the counter was talking with the older Italian customer just as if the scene were frozen since the last and only time Richard and I had stopped there.

The Italian man asked where Richard and I lived. Paris, now. And where did you live before? said the girl. Playa del Rey, a beach town in Los Angeles, I said. The Italian girl wanted to know why we’d rather live in Paris. The older man laughed. He knew. He moved to Paris from Bari some thirty years ago.

My pizza was ready. There was a booth at the back, near two women who were belting down red wine.

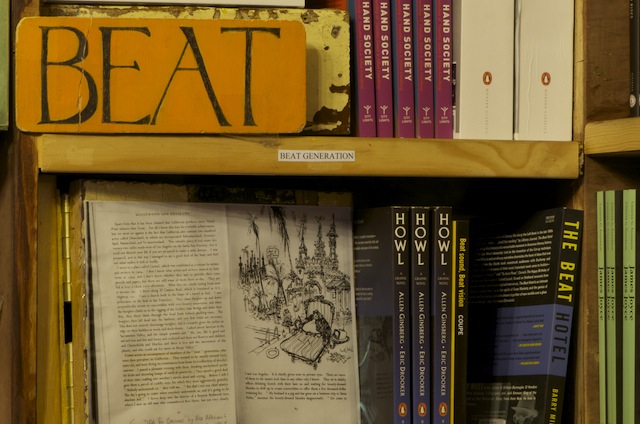

I opened my book, The Tenants of The Hôtel Biron. It’s a fictional account of the years when the house that is now the Musée Rodin was inhabited by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Rainer Maria Rilke, Auguste Rodin, Camille Claudel, Vaslav Nijinsky, Eric Satie and Jean Cocteau. I know, you want to read it, too, right? I read with special relish because the author, Laura Marello, had passed the manuscript to me about ten years ago when we knew each other in Los Angeles. I’d been knocked out by the story and the writing, felt it was publication-worthy then, and now, ten years later it had found its publisher, Guernica Editions. Do you have any idea how happy it makes me when a writer finally breaks through?

So I’m savoring the pizza, devouring the book, and the two women speaking Spanish behind me are growing boisterous with gaiety. One taps me on the shoulder and asks in French if I have a cigarette.

Non, je suis désolé, je ne fume pas.

She gets up to ask the only other diner, a man who looks like Serge Gainsbourg, for a smoke. He hesitates, gives her one, and she puts it in her mouth as if she’s lighting up.

You know it’s not legal to smoke in restaurants? I ask.

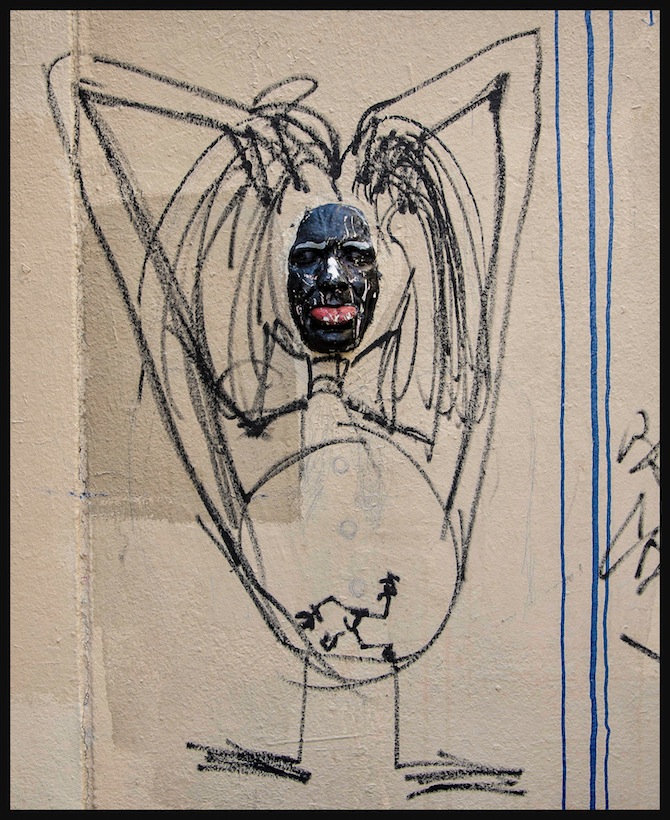

Street art (mask) by Gregos, additional artist unknown

Street art (mask) by Gregos, additional artist unknown

She scurries over to the edge of my booth and leans in and makes a face at me. Then walks outside to smoke.

Her friend behind me says, Forgive her. She doesn’t understand that you have to respect the cultural customs of the country in which you live. She has a problem with depression.

It’s okay, I say. For me it’s just a matter of health. I’m so relieved that France changed its laws about smoking in restaurants.

The woman and I banter in French. She tells me she talks to her friend about her surly attitude.

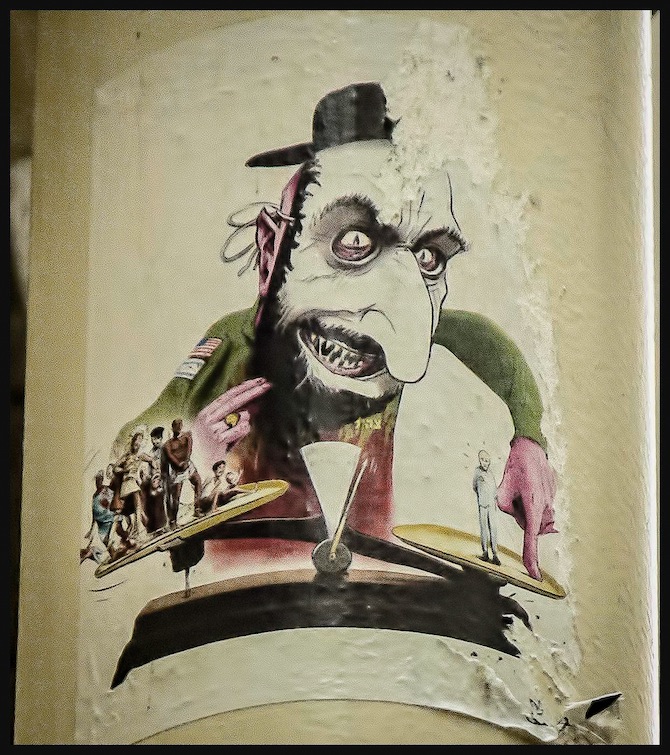

Street art by PopEye

Street art by PopEye

The smoker returns. She sits down, her back to my back but turns to look at me as I talk with her friend. She is drunk, with a sweetly cow-like expression on her face, melancholy eyes, and a sprinkling of freckles. Like her friend, she has very short hair.

We ask questions of each other. Discover we are from the same continent, only they are from South America.

It’s the continent of the heart, I say.

South America, maybe, says the older woman.

North America too, I say. It’s all one heart.

Then an odd conversation begins. The older woman begins to talk about her friend as if she isn’t there. She is too closed, she says. She stays at home and is depressed. She doesn’t have any confidence in herself.

The younger woman nods, That’s right.

The older woman says, We’re out tonight trying to cheer her up. Getting her out of her apartment. Having a little wine.

There are four empty bottles on the table.

We talk about living in Paris. I notice that the younger woman’s fluency in French, her accent too, is excellent, and ask her about it. She was educated in Paris.

The older woman is originally Basque—we have rebellion in our veins, she says. Her family emigrated to South America before she moved to Paris. She never wants to leave.

The younger woman asks me if I’ve read Stefan Zweig.

No, I say. Is he good?

Very good, she says.

Do you like Proust? I ask.

The two women shake their heads. There are certain moral problems it seems with Proust. (Do they mean that he was gay?)

Street art by PopEye

Street art by PopEye

He was Jewish, wasn’t he? the older woman asks.

Half Jewish, half Catholic, I say. He was raised as a Catholic, but really identified more with his mother who was Jewish.

I can see in their faces that there’s some difficulty in the way they regard this fact.

But you can’t be two religions, says the older woman.

Well, God, gods, spirits—what difference does it make?

They look at each other meaningfully. (Unspoken: a huge difference.)

You are Catholic? I ask.

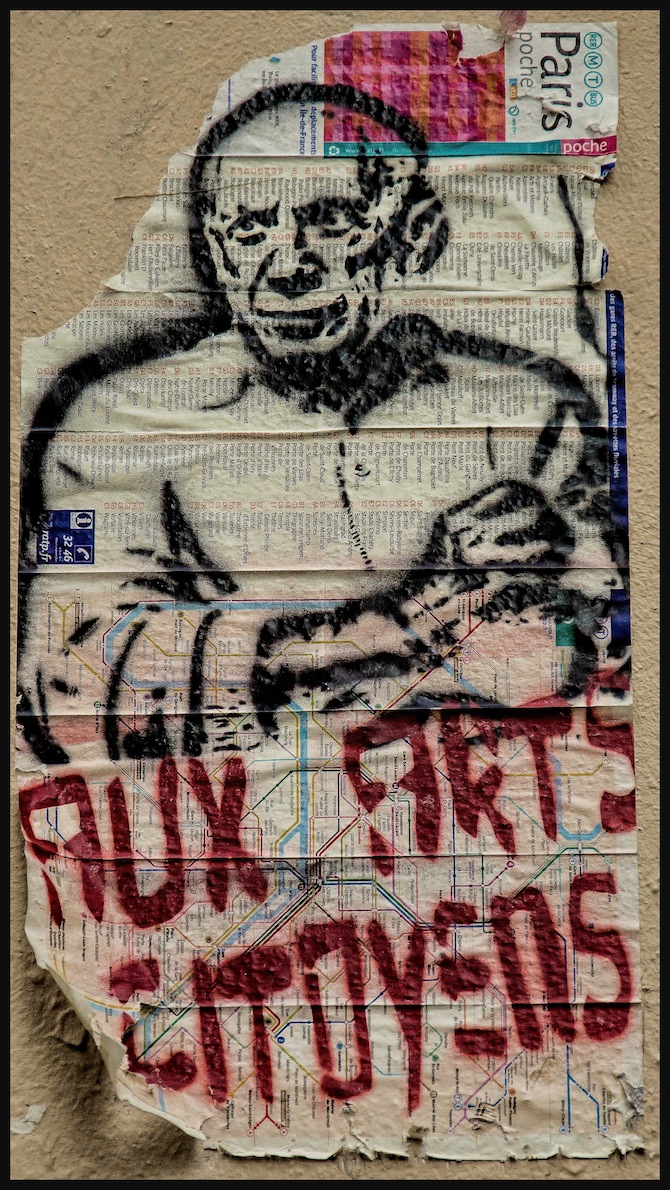

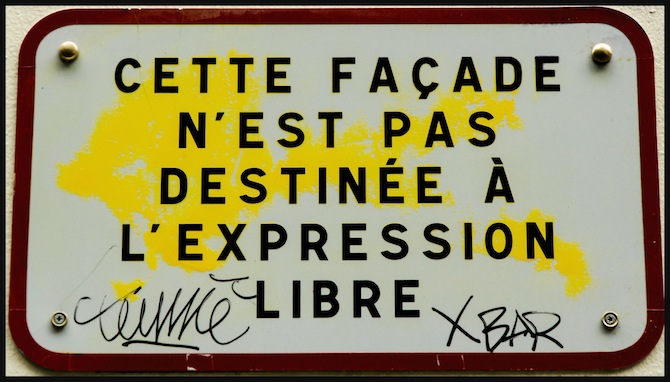

Anti-Israel/-American street art in the Marais, artist unknown

Anti-Israel/-American street art in the Marais, artist unknown

They both nod as if to say, Exactly. And then the older woman, her lips red with wine, begins to talk about Jews. How grasping they are. How they try to take over the banks.

No, no, no, I say.

How Hitler tried to save his country from the Jews.

Hitler was a monster! I say.

No, he was trying to save his country.

The Jews were not responsible for the wretched state of Germany after World War I, I say. Germany was economically ruined and Hitler offered a scapegoat, someone to blame. He was a failed artist, a maniac.

I suddenly see that a visor-like armor has fallen over their faces. There is no further place to go in conversation with these two. Closed minds. Time to go. I pack up my book bag and say goodbye.

And the Italian man who still stands talking to the girl behind the counter, says, Dites bonjour à votre mari. Say hello to your husband.

Merci. Et bonne nuit à vous.

Buona notte, says the girl with a big smile. California, she sighs.

I walk home thinking about bigotry and hatred. How an atheist Jewish friend of mine used to talk about Catholics, and mock my spirit helpers, who appear to me in the form of gods and goddesses. She is someone I love, but it cost the friendship. No one wants to have to defend his or her own spiritual beliefs, nor should any of us have to.

I think about how a recent online discussion of a well-known Native-American poet’s reading in Tel Aviv elicited a furor on Facebook. There were those who, objecting to Israeli bullying of Palestinians, said, Don’t cross the picket line. There were those who defended Israel at any cost. There were those who sent her love and blessings on her performance there in the role of poet and musician.

I identified, in some way, with all of them.

It’s so obvious. Peace and love are not clichés. They’re the answer. But when you encounter scapegoating and bullying, where do you draw the line?