Pan Speaks: (News From the Mythosphere, Part Two)

11.30.2011

11.30.2011

And here's The Waterboys song, The Return of Pan (with thanks to Steve De Jarnatt for the multimedia reference).

"All the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players." --William Shakespeare

11.30.2011

11.30.2011

And here's The Waterboys song, The Return of Pan (with thanks to Steve De Jarnatt for the multimedia reference).

11.26.2011

11.26.2011

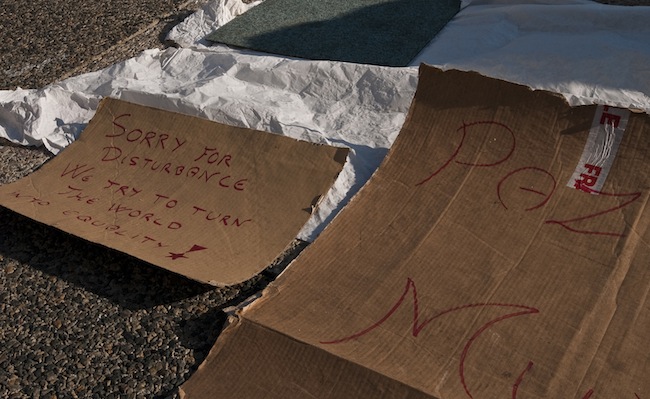

What on earth is going on?

The news on earth is demonstrations all over the world. Occupy Egypt’s Tahrir Square. Occupy Tunisia. Occupy Libya. Occupy Syria. Occupy Yemen. Occupy Wall Street. Occupy Berkeley. Occupy Oakland. Occupy Los Angeles. Occupy Davis. Occupy Seattle. Occupy Portland. Occupy Chicago. Occupy Denver. Occupy Boston. Occupy Washington D.C. Occupy Atlanta. Occupy Vancouver. Occupy London. Occupy Berlin. Occupy Madrid. Occupy Rome. Occupy Athens. Occupy Mexico City. Occupy Bogota. Occupy Tokyo. Occupy Sydney. Occupy Wellington. Occupy Cape Town. Occupy Paris.

What is moving so many people from so many countries into the streets?

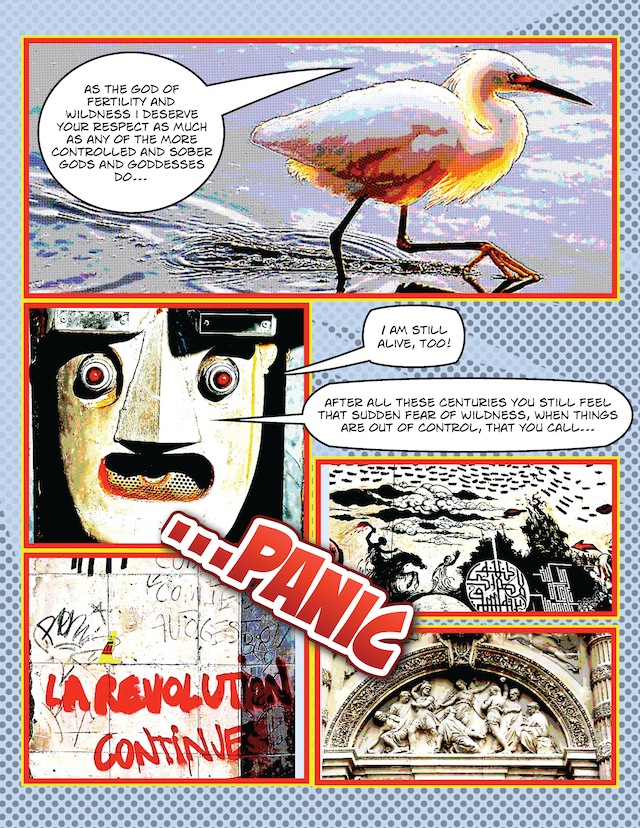

Panic and fear. Poverty. No jobs. Economic inequality. Rage at tyrannical government.

The U.S. is no different, but there it also involves the collapse of the housing market. Loss of homes. Rapacious banks, corporations and Wall Street. Unresponsive, ineffectual government gridlock. The rage of the 99% at the mega-wealthy who refuse fair taxation, while social services—education, health care, and every form of social security—are gutted.

Whenever there is a great shift in the zeitgeist, a paradigm change, there is chaos and confusion about what it all means. Where do you turn for a long-range perspective? We turn to myth. Especially Greek myth. The world’s myths contain all the stories that have ever happened, and will happen, over and over again.

A good friend who loves Greece as much as we do told us of a conversation she had with Henry Miller. The two of them agreed that the air is intelligent in Greece.

Whatever the reason, some of the greatest stories of the mythosphere, a word coined by our mythographer friend Alexander Eliot, come from ancient Greece.

Here are a few that come to mind lately:

The story of Rhea and Cronus.

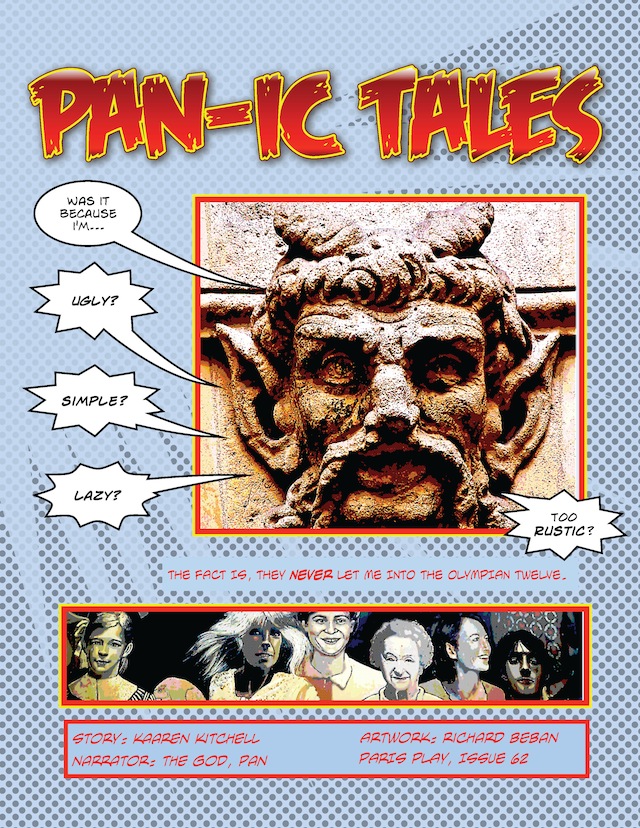

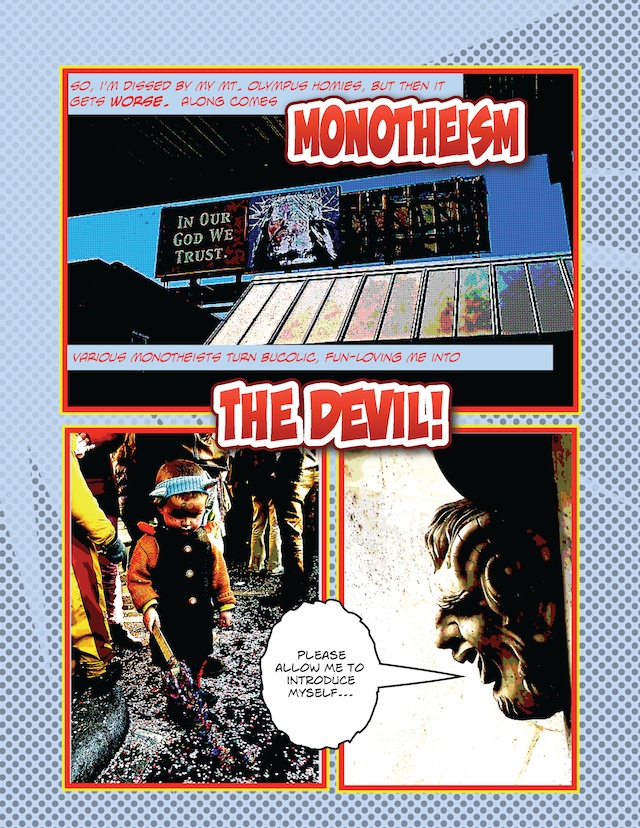

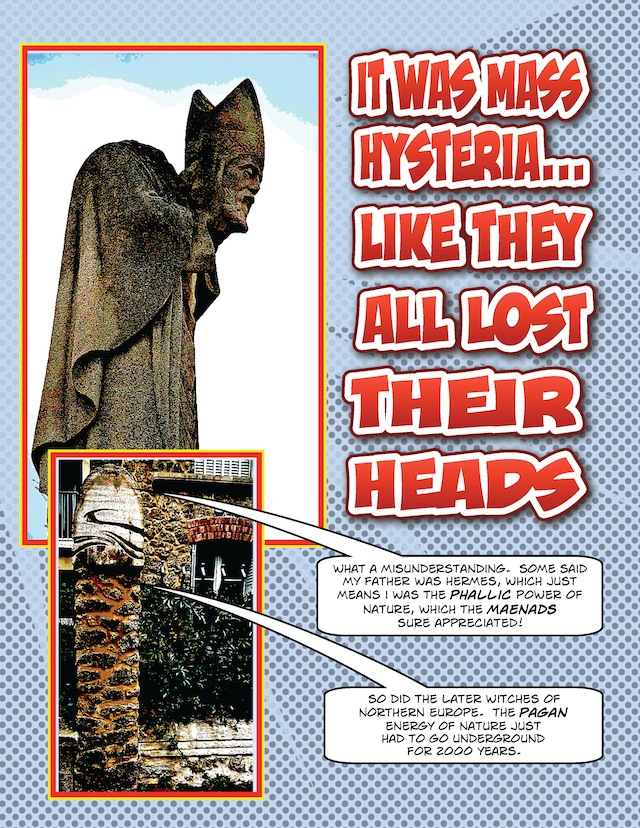

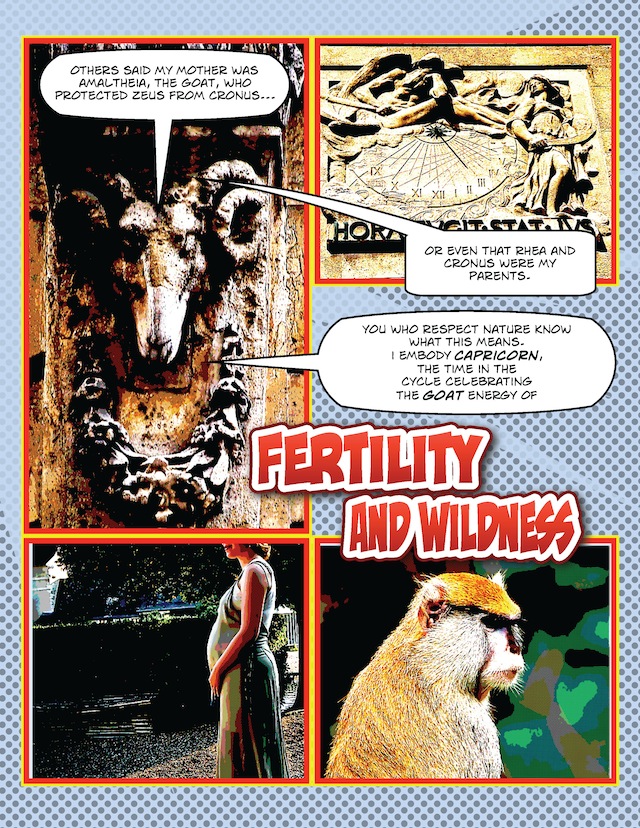

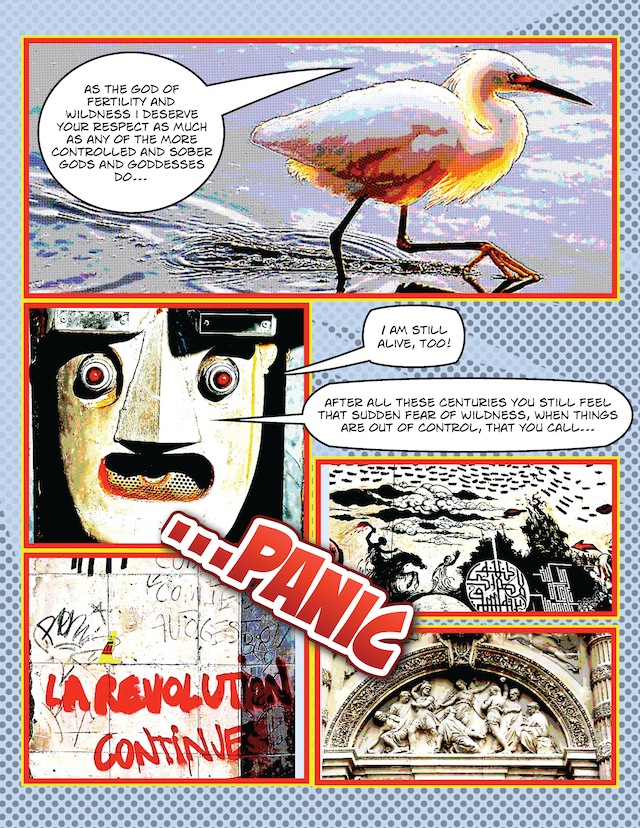

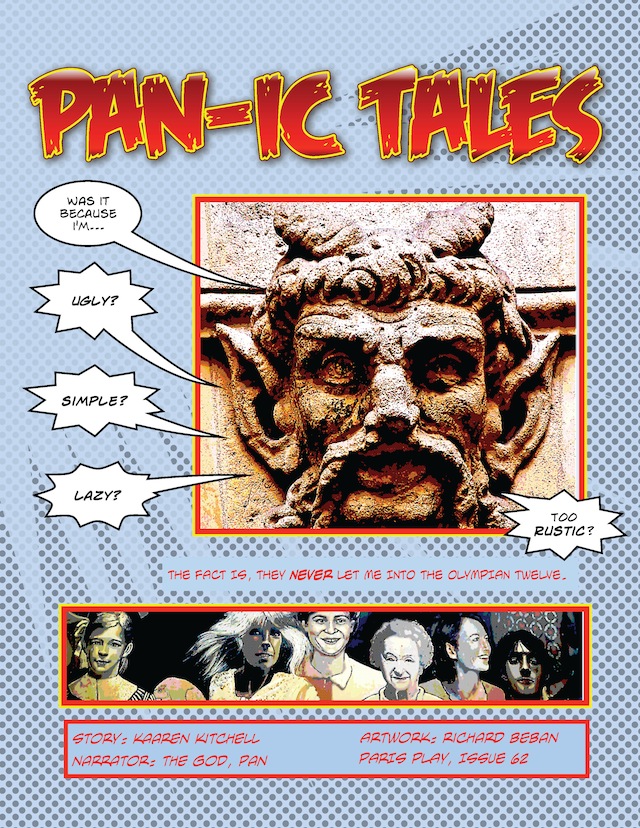

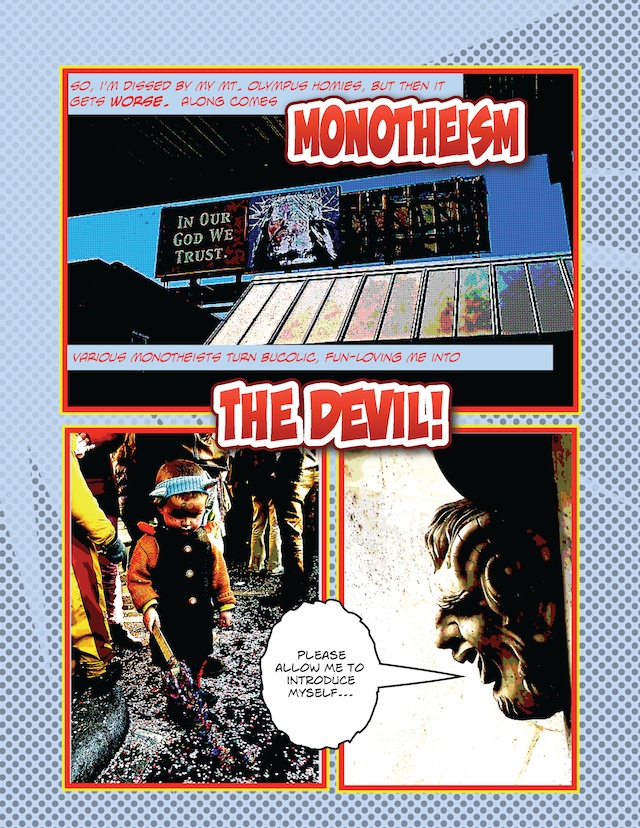

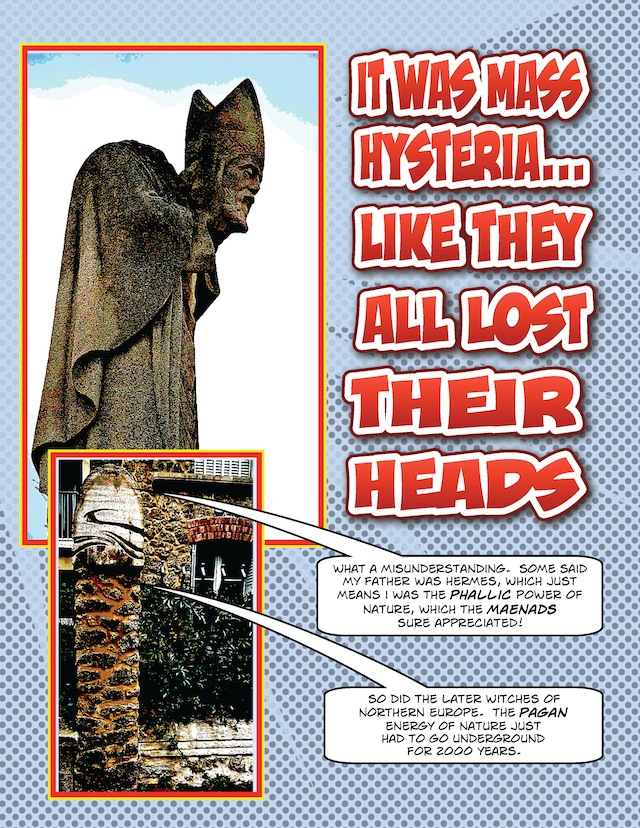

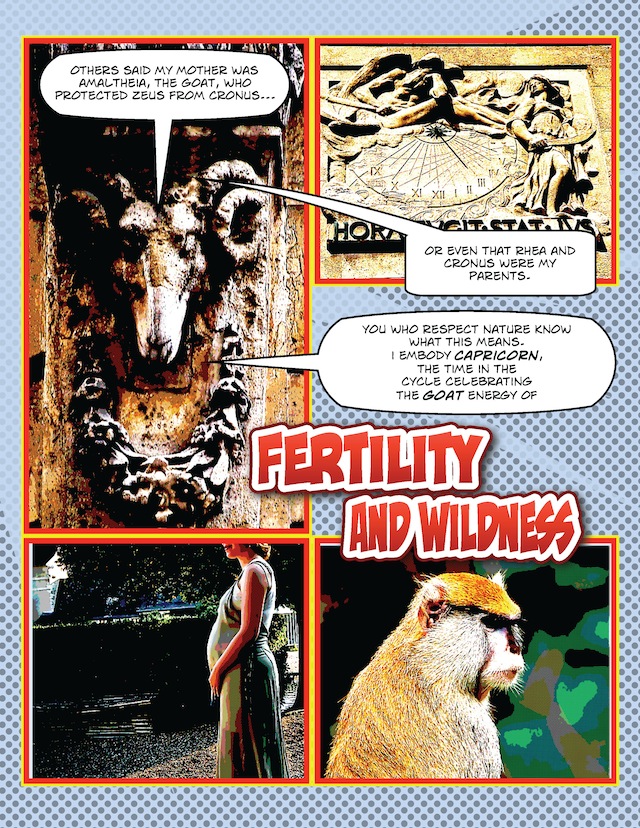

The story of Pan.

The story of Hestia, goddess of the hearth.

In three consecutive Paris Play posts this week, we’ll tell you three stories, with our take on how we think they’re connected to what’s happening right now in the world.

First, the story of Rhea and Cronus. According to the poet and writer on myth, Robert Graves, Rhea’s name probably means “earth.” Which suggests that she is that ancient goddess, Mother Earth, also known as Gaia.

Graves thinks Cronus’s name means “crow” or “crown,” rather than “time."

Robert Graves’ The Greek Myths is our major source, but this is a modern retelling.

Mother Earth and Father Crow: A Myth for this Decade

Mother Earth was enraged. Every time she gave birth, her husband, Cronus, would eat the child. Each year he’d swallowed one of them: first Hestia, then Demeter, then Hera, then Hades, and lastly, Poseidon.

They were not the healthiest family. She should never have married her brother, she knew that now, eons later. Their father, Uranus, had filled Cronus’s head with paranoia, convincing him that one of his children would knock him off his throne. But why have children, for gods’ sake, if you’re not going to share power and resources with them?

This time it would be different. This time she’d trick Father Crow. She would hide the baby from him. When her latest offspring, Zeus, was born in the middle of the night, she took him to a mountain, bathed him in a river, and hid him in a cave on Crete.

There he was raised by two sisters, Adrasteia and Io (known as the Honey girls), and the Goat-nymph, Amaltheia. Baby Zeus was fed honey, and goat’s milk from Amaltheia, and so was his foster-brother, Pan.

Zeus’s golden cradle was hung on a tree, so that Cronus couldn’t find it in heaven, on earth or in the sea. Rhea sent her sons, the Curetes, to stand around the baby Zeus, and drown out the sound of his crying by banging their spears against their shields and shouting. This was good noise, “white noise,” to protect the innocent from a callous oppressor. According to Graves, Curetes meant “devotees of Ker, or Car,” one of the names of the Triple-Goddess.

Rhea wrapped a stone in swaddling clothes and gave it to Cronus to swallow.

In yet another cave, Zeus was raised among shepherds in Ida. Everyone needs a safe place on earth to occupy, and even a cave is safer than being eaten by your own father.

As Zeus grew up, The Titaness, Metis, advised him to go see his mother, Rhea, and ask to be given the role of Cronus’s cup-bearer. More trickery was needed.

So Rhea gladly helped her son by giving him an emetic drink, which Metis had told him to mix with Cronus’s honey drink.

Cronus drank it up and vomited out the stone, as well as all of Zeus’s older brothers and sisters. They were so grateful, they asked Zeus to lead them in battle against the Titans, all those calcified Holdfasts who don’t share the wealth.

This war lasted ten years. Finally Mother Earth prophesied that Zeus would win if he combined forces with Cronus’s prisoners in Tartarus.

Zeus went to their female jailer, Campe, killed her, grabbed her keys and set free the Cyclopes and the Hundred-handed Ones, whom he strengthened with divine food and drink. This was really a movement of the people, of the disenfranchised, the 99%. The Many against the One.

The Cyclopes in turn gave three gifts to Zeus and his two brothers, Hades and Poseidon: the thunderbolt to Zeus, the helmet of darkness to Hades, the trident to Poseidon.

Hades, now invisible, snuck in and stole Cronus’s weapons. While Poseidon threatened him with his trident, Zeus zapped Cronus with his thunderbolt. Stealth, trickery and force were needed to overthrow Father Crow.

The three Hundred-handed Ones threw rocks at the Titans, and Goat-Pan gave a sudden shout which made them flee. Rocks and shouts, a riot.

The gods ran after Cronus and banished him and all the Titans except Atlas. Where? Accounts differ—perhaps to a British island in the far west, or perhaps to Tartarus. Anyway they were kicked out of power, and guarded now by the Hundred-handed Ones, whom they had once jailed.

Atlas was given the punishment of carrying the sky on his shoulders. It seems harsh, but perhaps it’s the cost of leading the forces of tyranny, which, worse than harsh, are lethal.

Zeus set the stone which Cronus had swallowed down at Delphi, the sacred place of measure. One of the phrases carved into the temple was: μηδέν άγαν (mēdén ágan = "nothing in excess").

The constellation of the Serpent and the Bears is said to be Zeus (who shape-shifted into a serpent when Cronus discovered he’d been tricked with a stone) and his nurses became the bears.

To thank the three nurturing nymphs, Zeus put the goat-nymph Amaltheia’s image in the stars—Capricorn!—and gave one of her horns to the two Honey sisters, which became the Cornucopia, the horn of plenty, which is always filled with whatever its owner wishes to eat or drink.

It had taken ten years of battle, but at last the people had food and drink and plenty, which is usually the case when kingdoms have wise rulers who distribute wealth instead of hogging it. Stone soup had been transformed into a nourishing feast.

Mother Earth was well pleased. Her children could flourish, and so, at last, could she.

11.19.2011

11.19.2011

11.12.2011

11.12.2011

Gold balconies. Plush red seats. A spectacular painted curtain in burgundy and gold, with a real rope pull.

We’ll look at the Marc Chagall ceiling later. Who are the gold figures on either side of the stage? Are they muses? Gods and goddesses? Richard thinks one could be Dionysus, with a mask of drama raised above his face.

The curtain rises. The orchestra music swells. Four blue fairies come springing out onto the stage. I’m flooded with tears. They are so light, so quick, and the music mirrors their leaps. One princess in white dances among them. Eight women in various pastel colors circle her. A fairy in pale yellow-green arrives.

Tears for the artistry of the French. Tears for our friend who is ill. Tears for the nine months of a neighbor who won’t be reasonably quiet “because she doesn’t feel like it,” and who’s hurting our sleep. Tears for someone I love who told me to stop writing this journal, and focus on fiction. Tears for all the women who for centuries have been silenced, told by their husbands or families not to work, to serve them instead.

Isn’t it strange how beauty can release sadness?

The yellow and blue fairies dash about the stage. A man in brown-green, a forest man, comes out among the trees made of ropes, and plays hide and seek with a blue fairy with a few sparkles on his skin.

Two by two, Cossacks in Russian fur hats and fitted coats and boots, march forth, followed by Cossack maidens. Okay, now we’re seeing Christian Lacroix’s costuming genius. Their skirts are orange and red and gold, with soft red boots.

He has interwoven brocade patterns that look perfectly Russian, and also like the dresses he designed as a couturier.

Out comes a carriage, a stylized version of Cinderella’s pumpkin, and a tragic female emerges, looking like a nineteenth century European version of an “Oriental” woman. Hot pink top with gold thread. Turquoise skirt with silver thread. A gold diadem atop her head crowned with a fuchsia pom-pom.

Twelve maidens dance all around her in long kerchiefs, Cossack costumes and soft red boots that you can dance in. That seems like a feat in itself, to make shoes that look like boots, but allow dancers’ feet to be en pointe.

A proud Cossack comes out on stage (you know he’s proud because he keeps holding out his arms straight, palms open in a gesture of Watch it, I’m in charge here). He dances with the Cossack princess, romantic, flirting, then with closed fists.

Then he does one of those Russian dances where you spin around and around. (I don’t, but apparently Russians do.)

Then, the princess points to a flower hanging from what looks like an orchid tree, suspended in the middle of the forest stage. The proud prince tries to climb up to get it, but his arms aren’t strong enough. He’s wasted all his energy on clenching his fists and pushing people away.

But the forest man can. He climbs up the rope and plucks a flower and hands it to the Cossack princess.

The prince is pissed, and fights with the forest guy, kills him, and puts the princess in the carriage and huffs off.

A white fairy princess dances out from behind a tree, picks up the fallen orchid and brings it to Forest Man. He slowly revives. She cradles the flower, he reaches for it, she dances away. They dance together; he lifts her into the air. He is a tree. She is a swan.

More fairies in white appear and circle the forest man. They dash away. Twelve more fairies emerge and all dance around the forest man and the white fairy princess.

The blue fairies and the yellow one join the dance, and then the yellow one passes the orchid to the white fairy princess, and threatening music begins.

Act One is over.

There is too much to see at the Opéra Garnier. It’s like walking around Versailles. You have to get a book to decipher all of its history and splendor, and luckily Richard finds one in the gift shop before we leave.

Act Two is full of intrigue, seductions and counter-seductions, so that you really don’t know who will win the Cossack woman’s heart at the end, the forest man, the proud prince, or Genghis Khan who only has about nine women already in his harem. But you can guess.

Later I learn that the proud prince was actually the Cossack woman’s brother, and that he was delivering her to the Khan. What I still didn’t understand was why one of the characters had to die. But I’m not going to ruin it for those of you who still haven’t seen La Source. This 1866 ballet was enchanting, but I did notice that all these women ever thought about was love. Didn’t they sometimes long for something to do?

And afterwards, we had drinks with two great friends who had invited us to spend his birthday at the ballet. We talked about boating around the rivers of Ireland. We talked about their plan to live part of the time in Paris. We talked about our beloved friend who is ill. We talked about my new challenge (inspired by TWO fairies), which is writing 1,000 stories in three years. A story a day, with one month off per year. I’m only on Day Three. But here’s my question: if those fairies in pastel could grant you a wish for your own work, your own artistry of whatever sort, what would it be?

I’m asking a serious question here. I want to hear your answers. What else can possibly balance all the suffering in the world if not work?

Oh yes, and love.

The pastel dancers in this article are from the streets of Paris, courtesy of the street artist Miss Tic.

Che Guevara,

Che Guevara,  Garnier,

Garnier,  Opera House,

Opera House,  ballet,

ballet,  dance,

dance,  love in

love in  Paris Life

Paris Life  11.5.2011

11.5.2011 On today's menu, the results of our second Surrealist Café community collage. Readers will recall that we asked you to walk into a cafe (or a spot that animals frequent) precisely at 1 p.m. on Saturday, October 29, and record, in whatever medium you chose (poetry, prose, drawing, photography, etc.), your interchange with an animal. We suspect most of you didn't follow the rules about time and space, but nonetheless, these contributors seized the time, and amazed us with their devotion to les animaux. All contributions are (c) 2011 by their individual creators.

* * * *

Suki Kitchell Edwards, passing through New Orleans, USA:

* * * *

Scott MacFarlane, near LaConner, WA, USA:

“Bear Box”

Can replica serve as artifact? The Northwest Indian bentwood box––with stylized bear design wrapped around four sides––hides in the clutter beside the register at the Rexville Grocery. Those pens sticking out the top were not native but reinforce how functionality was a trait of this rich art form.

Down the road from the Swinomish tribal casino, this is the prehistoric land of the Northwest Coast Indian. The red-and-black design with tertiary ovoids portrays a bear. The little ears differentiate it from an Orca design that would display stylized flukes.

A half-dozen miles from here as raven flies, killer whales swim. However, this totemized design––Tlingit perhaps––derives not from here, but from the tribal turf we now call Southeast Alaska. This design style was more formalized than local Salish art.

When I entered the Rexville, three aging hippies sitting at the counter glanced up and resumed talking. The pencil holder had caught my eye. Thirty-three years earlier at the Burke Museum on the UW campus, I had helped touch up these boxes, really a diminutive replica of a native bentwood artifact. Clear cedar had been silk-screened, notched, bent and assembled just down the hall from Bill Holm’s office in the basement. Holm was the non-native who devoted years codifying the principles behind Northwest Coastal Indian Art. He wrote the book.

* * * *

Stuart Balcomb, Venice, CA, USA:

Gaynia

The vet allowed me to hold her

during the injection.

She was deaf, blind, very much in pain.

I know she could sense my heart beating,

her nose against my chest

as her last few pulses faded into memory.

Wife and child couldn't bear to attend,

so I did the deed,

then carried the lifeless cargo back home

where I laid her to rest, deep in the yard,

and toasted her eternal gifts

with a teary glass of Beaujolais Nouveau.

* * * *

Joanne Warfield, "Birds, Flights of Fantasy," Venice, CA, USA:

* * * *

Jennifer Genest, Long Beach, CA, USA:

* * * *

Walt Calahan, Westminster, Maryland, USA:

* * * *

Bruce Moody, Crockett, CA, USA:

Les Animaux

(for Amanda Sidonie Moody on her birthday)

There are always animals about.

Here, there, up, down,

always about. Wild.

Beetles.

Butterflies mating in front of everybody.

The squirrel taking over the roof.

The bird you failed to notice

or identify if you did

overreaching all expectations in the sky.

Consider their quiet absolute presence

like a fur you wear and have become accustomed to.

Consider the tortoiseshell cat next door

and the grey one.

and the other.

They are as impervious to us

as we to them.

We live in concourse with them

as we make our ways

cooperatively like folks on crowded streets

Neighbors we never notice.

Neither talking to one another nor to you.

They are indifferent to us as a species

to our names and souls,

dismissive of our wishes,

as we of theirs.

But they abound,

they abound all around us.

In the walls.

Underground as worms.

In the fields as unseen moles.

Ambitious for and seeking, ever seeking,

as we,

Survival.

* * * *

Amy Waddell, Santa Monica, CA, USA:

Walk Lobster

Gérard de Nerval died on January 26, 1855 at the age of 46. That's not to say he did not enjoy a full life. A man who befriends a lobster, names that lobster and has the patience to walk said lobster every day has reaped life's riches in my book. Every day Thibault the lobster and Gérard the poet took air, as it were, in the gardens of Palais Royal in Paris. Sometimes their walks found them skirting the edges of the Seine. It is not clear if the blue silk ribbon that extended from Thibault's craw to Gérard's was necessary, or whether lobster or man determined the course of the walks. It is only sure that man and lobster walked together, sans pincer or boiling water-induced screams, for some years in old Paris.

"I have a liking for lobsters. They are peaceful, serious creatures. They know the secrets of the sea, they don't bark, and they don't gnaw upon one's monadic privacy like dogs do."

--Gérard de Nerval.

* * * *

Edith Sorel, "Day of the Iguana," Key Largo, Florida, USA:

* * * *

Richard Beban, Aquarium Tropical de la Porte Dorée, Paris, France: