We walk a half-hour through rain, wet from shoes to hair. I do not

care. We find the building off the Avenue de l’Opéra. In the foyer

are milling young—a few Adonises and nymphs.

A bulletin board: Mythologie Conférence, Rez-de-chausée, Salle

zéro[1]. We climb a flight of stairs, pass a mural of vigorous

muscular youths circa the ‘20s, doing calisthenics for the state.

We peek in a room, see dancers at the barre.

Richard darts into the bathroom.

I peek again. A miffed French woman with slicked back hair appears: “Nous

n’avons pas fini cette classe![2]”

Richard returns. We go up. We ask a woman if she knows the way

to the myth room. Down below, she thinks.

We go down to the basement. A Zen teacher smiles peace into us,

but Richard cannot feel it. He feels lost.

Up we go again. Wrong room.

Down we go to the main floor. I open a door that leads outside. Richard

snaps his fingers at me, as if I were a dog. I know it’s just stress. I follow him

into a small dark room with a mirror covering one wall. An empty dance

space.

A small Asian man enters. A tall heron of a teacher bustles in,

turns on the lights, sets up a slide projector and arranges notes on a

desk. One by one, men enter. One looks like an accountant in a

short-sleeved shirt. Another is pudgy, shifty. There’s a young,

sleepy Frenchman.

We unstack the folding chairs, Richard and I at the back. Am I the only

woman in Paris who loves myth?

The lecture begins. Slides on the screen. Hermes has wings on his

hat, his caduceus, his shoes. He is “légèreté de l'être, rapidité,

l'échange d'énergie, mais pas commercial, non! L'échange

d'énergie spirituel, comme dans les secrètes d’Égypte[3],” or

something like that.

This teacher understands the essence of these êtres divins[4]. Here is

Zeus, king of the gods, bearded, powerful, gripping his

thunderbolt. As Monsieur speaks of Zeus, the rumbling overhead

gathers in volume—a stamping of feet in a ballet class, or the

god’s thunder? A back window blows open behind us. One man

moves to close it. It opens again. Another man closes it harder. It

opens to the rain and noise of the sky and the street. Another man

closes it. It opens again. Zeus will not be shut out. We surrender.

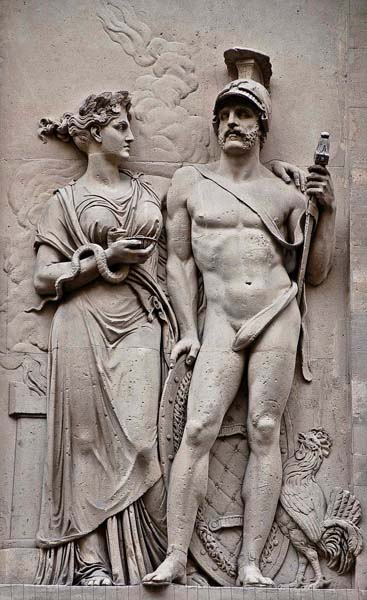

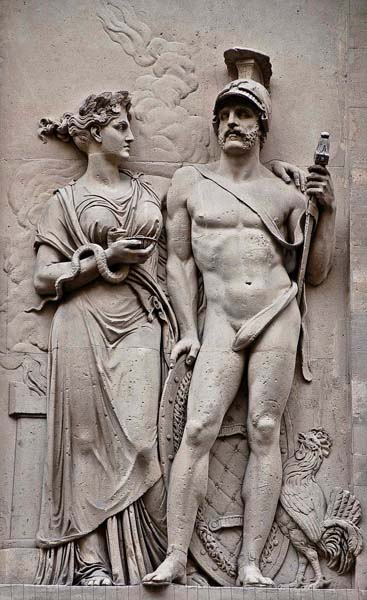

Here is Athéna, snake-haired Medusa on her shield. Perseus cut off

her head, freeing Pegasus, the winged horse of poetry. Athéna has

a creature on her helmet, resting on its haunches. Is it a lion? A

sphinx?

Athena and Ares

Athena and Ares

And here is Hephaestus, the ugly god. His mother, Hera, dropped

him from Olympus, and he limps, ankles broken. He is heavy,

lourd, and he works with heavy things, iron, making weapons, also

jewelry for the goddesses, lovely things for his wife, Aphrodite.

Look at Aphrodite! In this painting I’ve never seen, she is all milky

skin with pink blush, up on clouds like swans, and swans are riding

the clouds.

Her lover is Ares, god of action, of muscular body and war.

(I think of him as the god of Italy, its shape a boot for walking,

exploring, and hunting booty.)

Apollo is here in a painting with Daphne, who chose to become a

laurel tree, rather than sleep with him. A laurel wreath is now the

crown of achievement. He is inner beauty, says Monsieur. (But

I thought he was more a communal god of music and harmony.)

And here is Artemis, goddess of the hunt. Of the purity of nature.

Of cleanliness and chastity. When Actaeon happened upon her as

she was bathing, she turned him into a stag, and his own hounds

tore him apart.

And here is another painting I’ve never seen, of Hestia—ample-

bodied, in long dress, leaning against an altar holding a flame.

I am thrilled to hear his subtle understanding of this family I know

so well. Thrilled that I can understand much of what he’s saying.

Now he takes questions. First to wave his hand is the pudgy man

who’s been sneaking peeks at himself in the ballet mirror

the whole lecture. He asks a meandering question

about Aphrodite (of course!): “Elle, elle Aphrodite ... la bataille

entre le feu et l'eau .. la guerre à l'intérieur de nous ... les cygnes

la suite de son ... Zeus un cygne, un cygne ... Ares ai eue aussi, un

combat intérieur de ma tête,”[5] and who knows what else.

It’s painful listening to this question that never ends. The lecturer

grows tense and so do we. He tries to answer the man and move on.

I’m the last to ask. I agree with him, I say, on Hermes being about

spiritual exchange, rather than, as many say, commercial.

He suggests I ask the question in English. He’ll translate for the

class. Dang, I was so happy to understand, but I still can’t

voice what I mean. I ask him later about the bag Hermes

carries.

“Is it the sac[6] d’un égrue?” He looks confused.

“C’est un oiseau de l’eau[7],” I say. He doesn’t understand.

“Oh! Je veux dire, grue.[8]”

“Crane! Oh!” He gets it. But he doesn’t know.

We talk about the next lecture.

“It’s next Monday,” he says.

“Bon!”

But I forgot to ask, What was the animal on Athene’s head?

Who did the painting of Hestia? Who did the glorious Aphrodite

with white swan clouds?

The Invisibles take many forms in the imaginations of visionaries and artists

of every country, every time in history. The characters and shapes

of the goddesses and gods envisioned by the ancient Greeks have endured

over many centuries and miles. They still speak to us here today in Paris.

Hermes as Crane

Hermes as Crane

[1] “Mythology Conference, Ground Floor, Room Zero.”

[2] “We have not finished this class!”

[3] “lightness of Being, speed, energy exchange, but not commercial, no! The exchange of spiritual energy, as in the secrets of Egypt.”

[4] “divine beings”

[5] “She, she Aphrodite … the battle between fire and water… the war inside us…the swans following her… Zeus a swan, a swan… Ares got her too, fighting a battle inside my head,”

[6] “bag”

[7] “It’s a bird of the water.”

[8] “I mean, crane.”

08.30.2012

08.30.2012

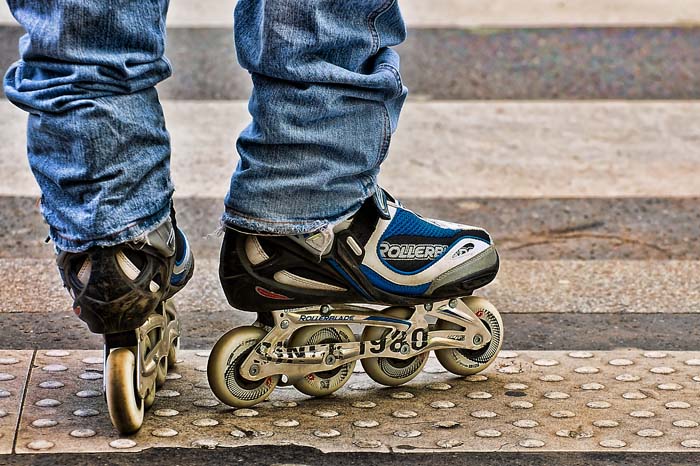

A Chorus Line

A Chorus Line Channeling his inner Gene Kelly

Channeling his inner Gene Kelly

A mosh pit

A mosh pit Sometimes, your hair can dance for you

Sometimes, your hair can dance for you A dog who thinks he's a cat

A dog who thinks he's a cat Dances with not-quite wolves

Dances with not-quite wolves

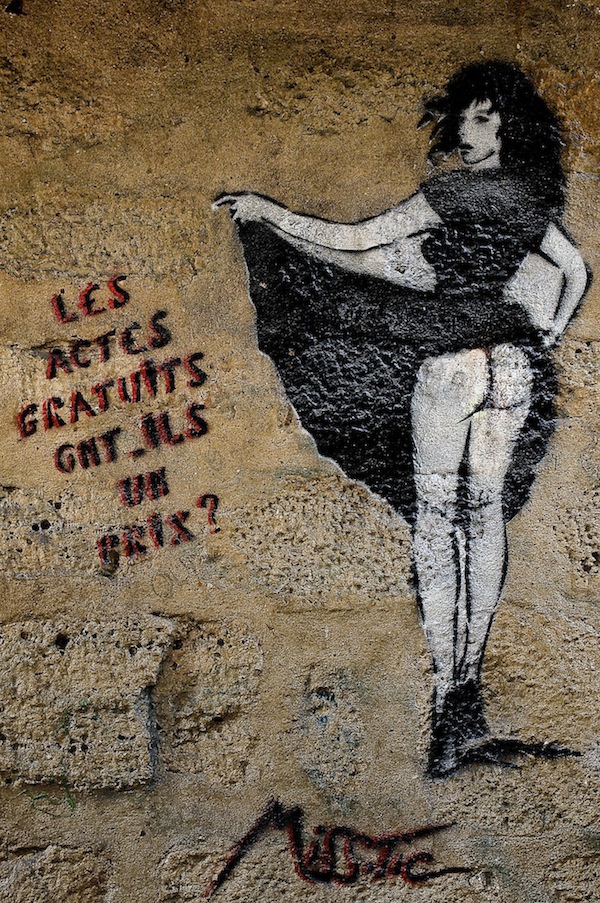

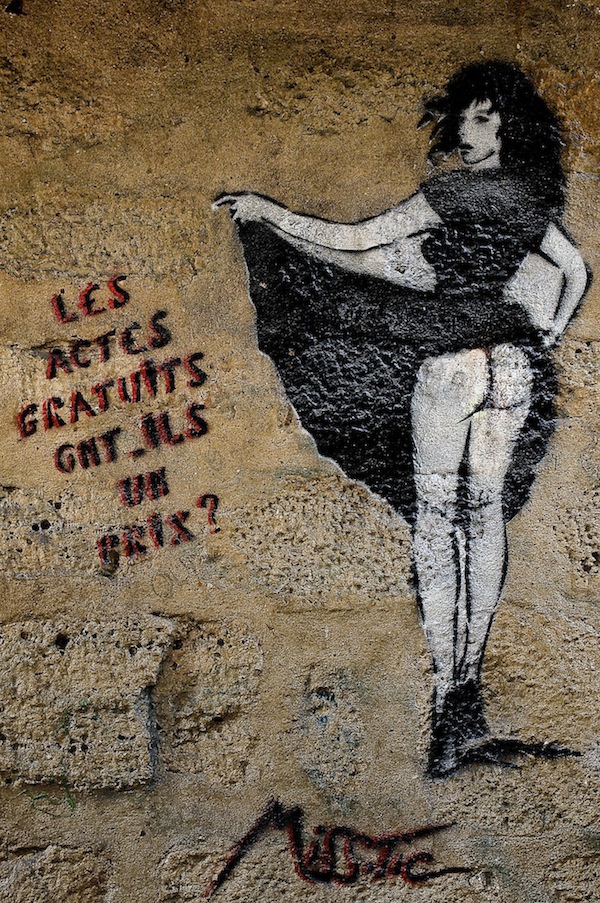

Street art by Miss-Tic

Street art by Miss-Tic

Catherine de Medici,

Catherine de Medici,  Louis XIV,

Louis XIV,  Sun King,

Sun King,  ballet,

ballet,  dance,

dance,  summer in

summer in  Paris Life

Paris Life