The Weave of Friendship

07.9.2011

07.9.2011

Tuesday was blazing hot, almost Arizona hot, but in Paris, you simply wait ten minutes and the weather will change. We didn’t know if we’d need sweaters, but we carried them just in case for dinner on Mort and Jeannette’s boat on the Seine.

We did know that we needed to bring a very good chocolate dessert, since this couple leads chocolate tours of Paris.

As we walk from the Concorde Métro to the Seine, other boats float through my imagination:

The barge where I lived on the Thames as a student in Oxford.

The schooner on which I crossed the Pacific from Honolulu to Marina del Rey, and on which I lived for two years while we renovated the ship.

The bateau mouche we took with my niece and her boyfriend the previous weekend. We’d pointed out Mort and Jeannette’s boat as we motored by.

Rivers are the circulatory system of the earth’s body, boats and their cargo the cells carrying nourishment and oxygen and ferrying toxins away.

We cross the larger boat to which Mort and Jeannette’s boat is moored, and see four old friends. Tonight, every cell that surrounds us promises to be nourishing.

Mort, a combat reporter who is the former editor of The International Herald Tribune, and writer of numerous books on food, the Seine, journalism and travel, wears wonderful round tortoise shell glasses and looks fresh and rested in spite of having just finished co-leading a ten-day tour of Paris.

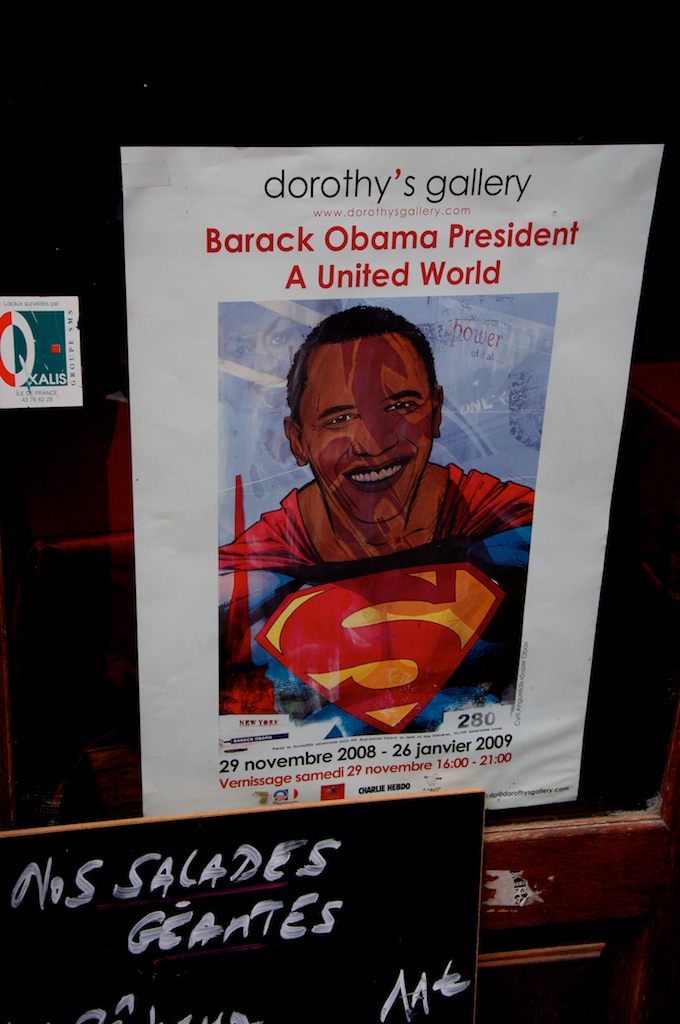

We talk of Obama, our hopes and our disappointment.

Phil has just co-led the tour of Paris, and right before that, gave lectures on a Mediterranean cruise. Though he’s still standing, he seems paused at a point of stillness, between breaths, gathering energy for his next Sisyphean task.

Porter is overflowing with good spirits. He and his wife, Louise, have just found a magnificent apartment for a well-known novelist in a chic part of Paris a block from Catherine Deneuve, and he and Louise are about to renew their wedding vows in a second ceremony in the Loire Valley.

The boat has a canvas canopy, open to the sides, and the table is set in Jeannette’s usual charming fashion.

Jillie, Mort and Jeannette’s neighbor in this houseboat village, steps on board. I recall meeting her on this boat several years ago. We had talked of my joining her on one of Jeannette’s labyrinth walks in Chartres Cathedral.

Jeannette brings up dinner from the galley. Garlic buds, cherry tomatoes, and marinated endive. Wine and hard cider. A curried fish stew with vegetables and rice and fresh bread, followed by a salad, and two cheeses, Roquefort and Camembert with a baguette.

Our interwoven stories began on Richard’s 1983 trip to Paris, when he met Porter, a Beaux Arts painting student who financed his studies by importing and selling “Louisiana” pecans. The French love Louisiana. Instead of returning home to Birmingham, Porter stayed in Paris and began to buy, renovate and manage apartments as rentals.

In 1984, Richard met Phil in Marin County, where Phil was teaching Myth, Dreams and the Movies, inspired by his encounters with Joseph Campbell, whom he would later celebrate in a documentary and book.

In 1986, Richard and Phil covered the Cannes Film Festival, then both helped Porter renovate a flat in Paris.

In 1988, Jeannette, a top-notch San Francisco travel agent who had helped Phil organize a tour that featured Mort as a speaker, met Mort in Paris and stayed. Richard and his stepmother were here for that tour and witnessed the burgeoning romance.

And in 1994, on this very date, Richard and I met at a poetry reading in Santa Monica, and so I joined this web of friendships and stories.

In 2006, Porter helped us remodel our Paris apartment.

The weaving is intricate and full of refrains: Two of us grew up in Arizona. Three have roots in San Francisco. Four of us are writers. Six of us are American. And six of us, not the same six, live in Paris. Four of us lead tours of Paris. Four of us have lived on boats. Four of us are obsessed with myth. And all seven of us loved Woody Allen’s newest film, “Midnight in Paris.”

I ask Jeannette what is in the stew. In her usual low-key, self-effacing tone, she says, “Just fish; and I threw in all the vegetables in the fridge.”

Jillie tells a story of her cat awakening her with a paw on her face, just before dawn. She heard a noise, came out of the bedroom in her tattered nightgown, and into the salon, to see a man standing there.

She gently and calmly talked him into moving up on deck, as skillfully as Athena, weaving peace where another might incite a dangerous battle.

Her neighbor on the next boat spotted the man and yelled at him. Instantly, the stranger’s aggression flared. Jillie pantomimed behind the man’s back, “Should I call the police?”

Her neighbor nodded yes. In three minutes the police were there, and took the man away.

I’m impressed by the cool-headed savvy with which Jillie handled the break-in.

Mort tells the story of their cat not waking them up several days later when intruders walked across the deck of their boat, though they heard the footsteps and scared the men away.

Porter tells how his father, facing a diagnosis of terminal cancer, gained seven more years by researching and writing a book about his grandfather, who commanded a battalion of “buffalo soldiers” after the Civil War.

I tell a story of driving cross-country to Key West, and stopping for water at a 7-11 in Georgia. Startled by the enormous amount of ammunition on the shelves, I asked the woman clerk what it was for.

“Why, for killin’ things!” she said, as if I were the oddest human she’d ever met. “Squirrels and deer and such.”

Phil tells how this most recent tour overlapped with the fortieth anniversary of Jim Morrison’s death in Paris, and how the throngs gathered at the rock singer’s Père-Lachaise grave wanted to touch him, like some holy relic, when they found out he had co-authored The Doors’ drummer, John Densmore’s, autobiography.

The bateaux mouches pass by, ablaze with light. We turn to wave, and Richard points out, on the opposite bank, the narrowest building in Paris.

Wind comes up and lashing rain; we dash below deck to fetch our sweaters and jackets, and the wine and stories flow on. And, thank the gods, everyone loves the chocolate cake from the best pâtisserie in our neighborhood.

This continuing weaving of stories and lives has been alchemized by Jeannette. By inviting us all here, setting a beautiful table, “throwing together” a meal—by creating this ambience, she is Demeter, goddess of the harvest. And Penelope, who invites the weaving of stories, while her husband still travels to war zones to cover breaking news.