Unexpected Pleasures

03.11.2013

03.11.2013

You can walk out into the world thinking you know what pleasures await you, and have no idea of the treasure in store.

I knew the dinner would be excellent.

I knew that editing a story would be satisfying.

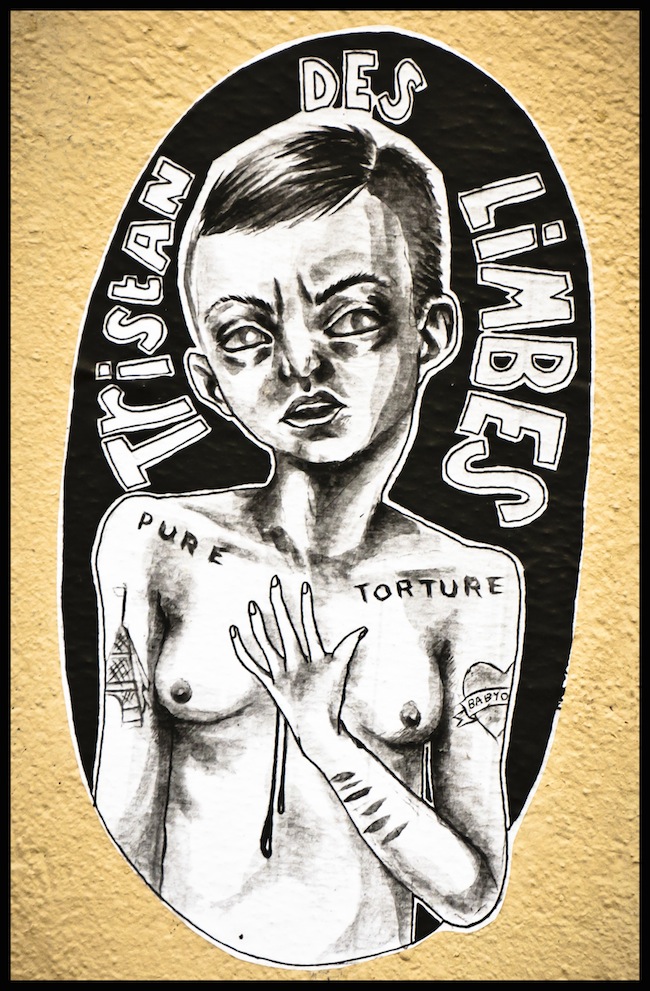

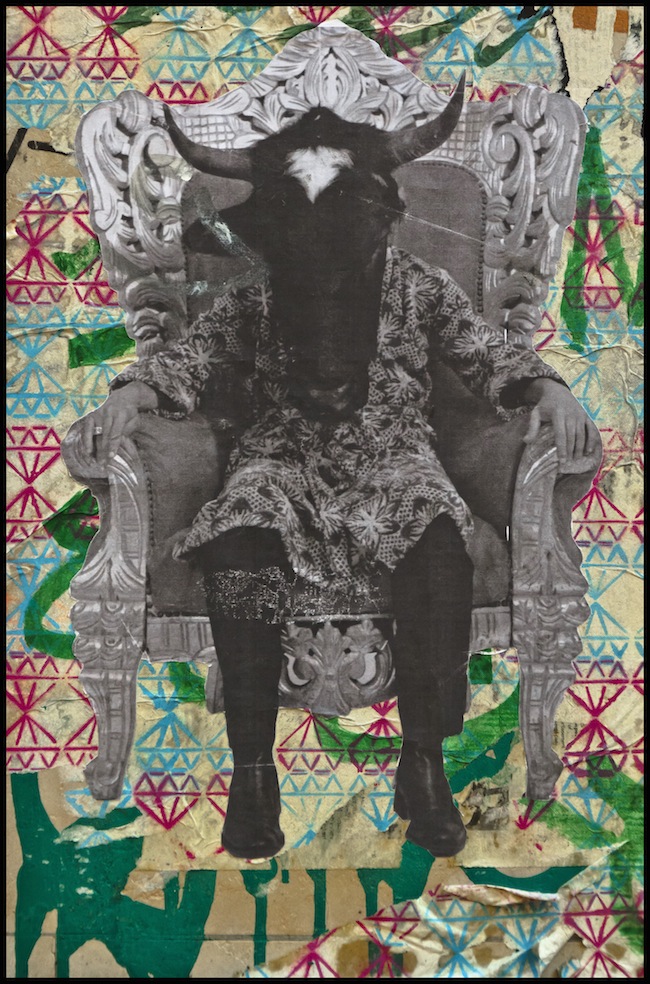

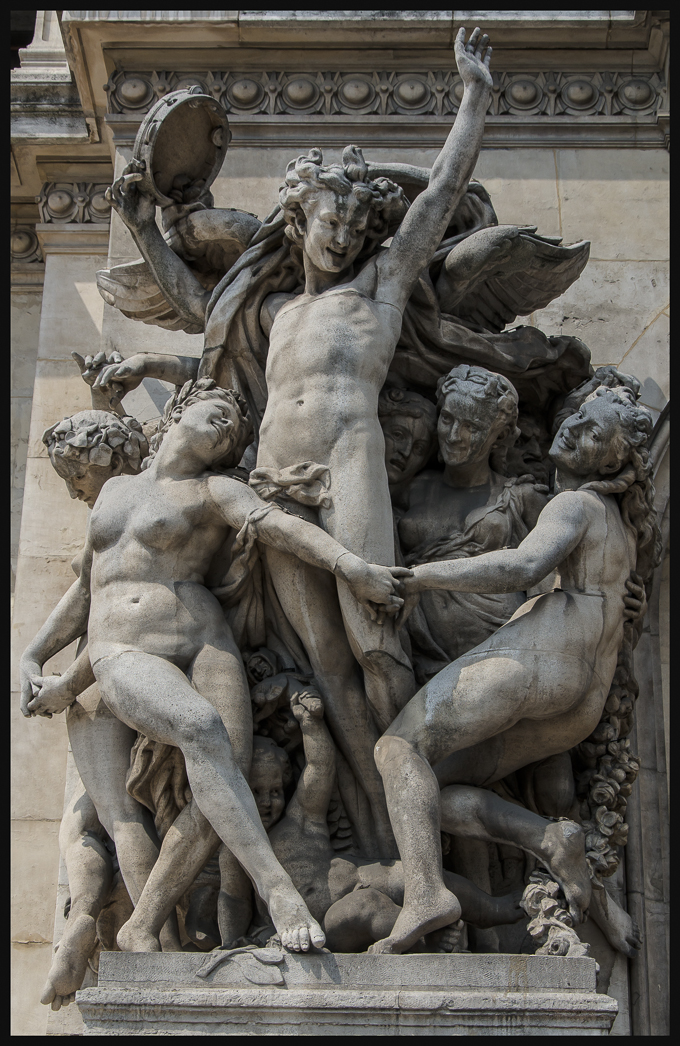

But I'm startled by the acute pleasure of being out in the cold sharp night air after several weeks mostly indoors with the flu. The world is so… solid, so real! Feathers! Flowers! Carytids! The moon!

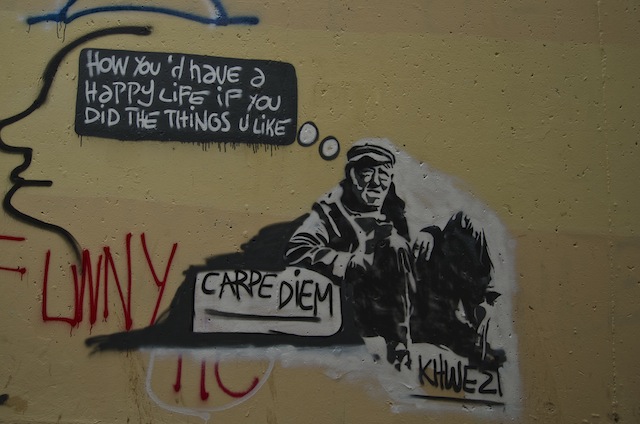

The pleasure of crossing a narrow street at the crosswalk, three men talking and blocking my path, the one on the bicycle looking up with great sweetness, "Oh, pardon!" and backing up his bike to let me pass.

The sweetness of men! It moves me even more than their strength. That Celtic douceur that comes from centuries of the troubadour tradition of courtesy (and perhaps from centuries of its opposite, savage wars on one's own soil).

The pleasure of remembering that I have several books to pick up at Shakespeare and Company. I'm carrying a book bag with my laptop and printed-out stories. Do I want the extra weight? Sure. Better than swinging by too late after they've closed.

I detour, pick up the books. The bookseller with whom I'd been exchanging messages says, "Oh, it's you. I know your face, but didn't know your name."

"Same with me. You have the slightest accent. What is it?"

"I'm French."

"But your English is perfect."

"I lived in the States for a while."

Out into the blue-black cold. The face of Notre Dame across the river makes me think of Rosamond Larmour Loomis. The cathedral reminds me of those four years of boarding school, of memorizing hymns, the strict regimen of classes, study hall, every hour mapped out.

Rosamond was the headmistress of the school. She died last week at the age of 102, several weeks after her boyfriend Henry.

I remember two conversations with her, one when I was 14, and had been called into her office with Miss Moran, the sadistic assistant headmistress. I’ve already mentioned this once on Paris Play, but it made a deep impression on me, hinted at my future. Miss Larmour sternly addressed a most unfortunate incident involving naked girls in high heels and pearls stampeding down the dorm singing an aria from La Traviata. She said, "We thought you were a leader when you arrived, but this is not what we had in mind."

And later at a school reunion, she was no longer the strict head of the school, but relaxed, warm, ageless. We discovered that we'd both been married for the first time later in life, at the same age, though years apart.

Rosamond died the way I would like to die, quickly, quickly, well past the age of 100, with my beloved and friends nearby. I imagine her on her journey, sailing into the mystery.

It is crowded at my writing café. But maybe, maybe that man is not sitting at my table.

The waiter asks.

No, he's just spread out his packages there from the adjacent table where he's talking with a woman. He graciously makes room for me.

I order salmon and scalloped potatoes, the way my mother used to make them.

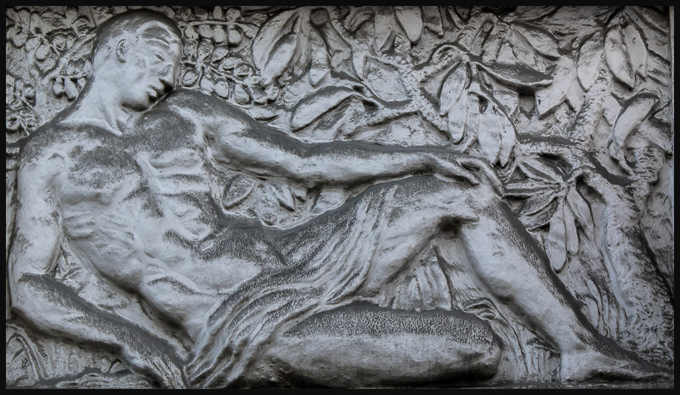

I open my new James Salter novel, Light Years, and begin to read. Oh. my. god. Oh! Oh! This is music. I cannot help it, I begin to annotate the page with a pencil, making scansion marks above the words as if the lines were a prose poem.

The rhythm of his sentences, the sculptural quality. The weather, the sensory richness.

I know these characters, their lives rich with art, books, friendship, family, storytelling, animals, weather, beauty. (And later, carelessness, sad choices.)

The dinner arrives. The waiter says, “If you finish that book tonight, I’ll give you a free dessert.”

The couple next to me laugh. It's a joke Parisian waiters make only when it’s clear that you’ve just started a book.

The meal is fantastic.

The man at the next table gets up to use the bathroom. The woman strikes up a conversation with me. She lives for literature. She lives in a small town near Brittany.

The man returns. He runs a poetry and fiction reading series near us in Paris.

She invites Richard and me to visit her in her small village. She offers to drive us around.

He invites us to come to his poetry series next weekend.

They have just met in the Jardin du Luxembourg. We all exchange cards.

I am flooded with richness.

When they leave I order a glass of cider. The mild alcohol content won't interfere with my editing.

Oh yes it does. I'd forgotten the lingering effect of the flu, am instantly tipsy. Now, how to balance that out? A coffee would keep me up all night. But a hot chocolate wouldn't. That delicate balancing act we do with food, drink and energy.

The hot chocolate warms and awakens me. I edit the story with the music of Salter's sentences ringing in my ears.