Chocolate Soup

02.14.2012

02.14.2012

Snow is predicted for tomorrow, but tonight it’s just cold. Nonetheless we go out to meet our friend in layers, and I’m glad to be wearing my new lined wool mittens from Le Vieux Campeur.

It’s a straight shot to her apartment on Blvd. Saint-Germain. We pass the UGC theater and muse upon which restaurant we’ll go to for Valentine’s Day, which film we’ll see. How about The Descendants, in honor of our friend Kimo, who grew up in Hawaii, and whose birthday was yesterday? We’ve just discovered that each of our closest friends from college age was born on the same day. Kimo and Polly.

We hold hands as we walk and talk. Richard is in such good spirits lately, it makes me happy too.

He stops suddenly and crouches. A python on the sidewalk! Or rather, a python-nosed shoe, scuffed, muddy, abandoned. It’s the shoe of a fashionable Parisian. As Richard clicks away, I ponder how it was lost. In this weather, surely you would notice the loss of a shoe? Unless you were drunk. Or lately homeless.

Farther on, we come to the statue of Diderot. On one side of the base I spot a stenciled Cupid, holding a machine gun, a red heart over his head. Richard photographs that too.

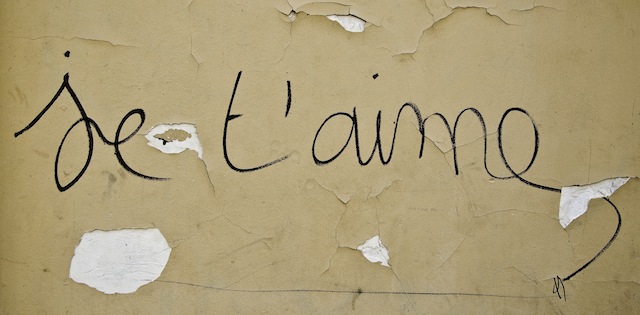

I tell him of an idea for Paris Play: some of us are paired up this Valentine’s Day, some are not, but almost all of us have been in love at one time or another. I’d like to hear others’ stories of how they fell in love with their current love or one from the past.

He suggests we approach it through the senses. What was the first sense that drew you to the beloved? Like your poem, he says.

Sight, sound, smell, touch, taste. 150 words. Or an image. Or a piece of music. Or a meal.

We meet our friend at her apartment and walk to a Japanese-French restaurant on rue du Dragon. She was born in the Year of the Dragon, she says.

“So it will be a good year for you.”

We know what we want: she and I will have salmon, he will have beef bourguignon.

This waiter is so charming! A quick slender young Frenchman, his spirit so friendly and clear. I ask if I can have scalloped potatoes instead of carrots.

Our friend hasn’t heard this American term. “Scallops—Coquilles St. Jacques?” she asks.

No, scalloped, and I motion to show the waiter that I mean sliced potatoes. Oh! Pommes de terre grillées, he says.

Our friend sits with her back to the window, facing the two of us. We talk about the past week’s problems, as well as the usual bliss. Water is dripping from her petit coin into the apartment below. Her heat went out. The count who lives in her building came to fix the heater. This just never happens in L.A., counts who double as plumbers.

For a solid week after we posted “Trouble in Paradise” about our noisy neighbor, she was quiet. Quiet at night, quiet in the morning, quiet all day long. We nearly wept with relief. We attributed it to Group Mind acting on her psyche. Really. What else could it have been but the good wishes of friends and family zipping through holes in space and time and persuading her towards neighborly peace. We turned off our fan at night, since we no longer needed the white noise.

But a week later she started up again.

We talk about Paris apartments. Our friend was of the same mind as her friend, Jean-Paul Sartre: best to own a minimum of possessions, including property. But then her mother died and another friend persuaded her to use her inheritance to buy an apartment, and oh, how glad she is that she did.

I had the same attitude, I say, until I drove into Santa Fe the first time. Driving from the Albuquerque airport over the last rise, and seeing the city like a bowl of jewels in the valley below, I knew I would put down roots there, and buy a place, and I did.

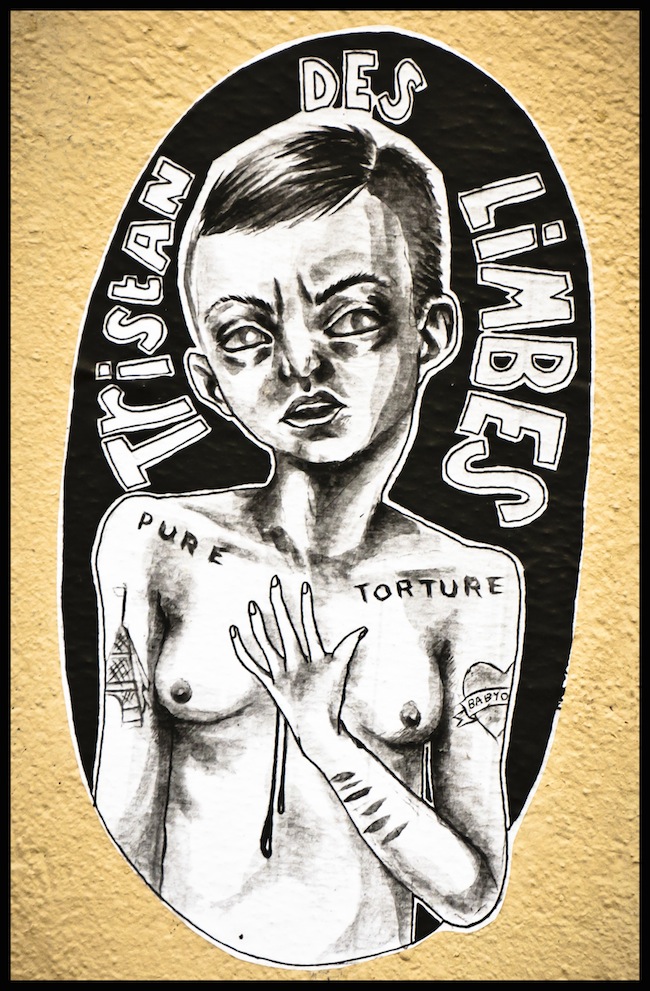

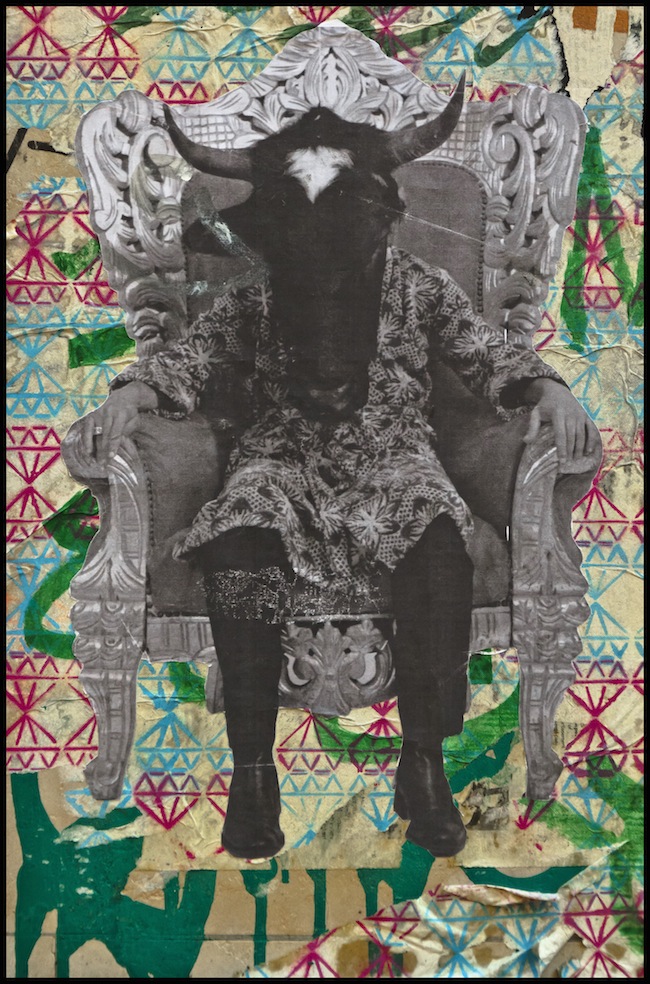

We talk about a dinner that our friend had with the film director, Michelangelo Antonioni, and the actress, Monica Vitti, in the old part of Nice. Antonioni spoke some French, but was not familiar with a certain Niçois dish called amourettes. What was it? he asked our friend.

“Bull’s balls,” she said.

The testicles of a bull. Antonioni balked. “Michele, why don’t you order that,” Monica said. “It’d be good for you.”

“What?!” I say. “I can’t think of anything worse you could say to a man. Were they a couple at the time?”

“Yes,” she says.

It’s hard for women to get roles past a certain age. More so if they are sex symbols than character actresses. Think of Meryl Streep. She’s still going strong.

Anyway, that’s changing now that women are becoming directors and producers and screenwriters.

Richard tells of interviewing several female directors, including Gillian Armstrong.

We don’t eat sugar. Sugar isn’t good for you. But we honor Apollo, and the words engraved in his temple at Delphi, μηδέν άγαν (mēdén ágan = "nothing in excess"). Not too much of anything, including purity.

So let’s see if there’s something on the dessert menu the three of us can split. How about this: Chocolat dans tous ses états. Chocolate in all its states.

Now that is a great title for a dessert. And it includes a little cake, a mousse, ice cream and …yuk! soup?

No, let’s choose something else. What an idea: chocolate soup.

But we are metal returning to magnet. Chocolat dans tous ses états.

Richard, being the consummate gentleman that he is, offers to protect the two women from the unfortunately named chocolate soup, and handle that problem all by himself.

This could be an alchemical revelation: chocolate as water, air, earth and fire! Oui, celui-ci, avec trois cuillères.

And it arrives on a square white plate, four delicate offerings amidst chocolate powdered right on the plate: un petit gâteau, mousse, crème glacée, et la soupe.

It’s so aesthetic, so Japanese, so lovely we almost can’t dig in. For a few seconds. There are perhaps two bites of each for each of us.

But a furious question consumes us: soup is the wrong word for this liquid chocolate. We must help the restaurant to rename it. Three writers go to town. Syrup, Liquide. Tasse. Nectar. Boisson. Soupcon. A waterfall. A pour. Aztec. Maya. I want to name it Ambrosia.

The waiter approaches. We tell him our conclusion: the word soup has to go. “How about ambrosia?” I ask.

He smiles agreeably.

When he leaves, our friend says, “You don’t think he understood the word ambrosia, do you?”

“He seemed to,” I said. “Why not?”

“No. No, when I studied at the Sorbonne, I thought everyone was familiar with the Surrealists and French literature and European history. But most of the students weren’t. And it’s gotten worse since. Nobody knows anything any more.”

We go back to dreaming up a better word than soup, all agreeing on the felicitous title, Chocolat dans tous ses états.

The waiter returns with the check. “What is the French word for ambrosia?” I ask.

He looks puzzled.

I try to Frenchify it. Ambroisie?

He doesn’t know the word.

Oh dear, she’s right.

Across the street a great green door opens in the middle. A French car slides in through the opening and disappears. The door swings shut. “Look!” I exclaim.

“This is the first time I’ve ever seen it open for a car,” she says. “When they were renovating the building, homeless families camped out in the courtyard. I’d bring them food. The count brought everyone hot coffee each morning.”

A circle of lights is blinking to one side of the doors. I glance up. Men and women pass by the window in their Russian hats. Dots and dashes of white Morse code are being sent from heaven to earth. Or maybe it’s ambrosia. “It almost looks like snow,” I say.

The huge green doors open, and the car departs. We all turn to look. And see the first snow of the night falling.

* * * *

Now we want your stories. Remembering how you met a current or past love, what was the first sense that drew you to the beloved? Sight, sound, smell, touch, taste? 150 words or less. Or an image with a 150-word caption. Or a short piece of music. Or a meal. Or a food doodle.

Get your contributions in by e-mail <textfile@mac.com> to us by 6 p.m. Paris time on Saturday, February 19. We’ll publish the best contributions as a Paris Play post next Tuesday, February 21.

We're waiting, senses alert.